![header=[Marker Text] body=[A Delaware Indian of the Munsee branch, he exemplified the spirit of reconciliation. He lived on 315 acres northeast of here, patented to him by the Penns, 1738. Tatamy was the first Native American baptized by the famed David Brainerd, 1745. An interpreter, he undertook many diplomatic missions. The borough of Tatamy, incorporated 1893, was named for him.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-215-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h5b8-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Moses Tunda Tatamy [Indians]

Region:

Laurel Highlands/Southern Alleghenies

County:

Northampton

Marker Location:

8th and Main Sts., Tatamy

Dedication Date:

May 14, 1992

Behind the Marker

The missionary David Brainerd could tell that God was at work on his Indian interpreter, Tunda Tatamy. Tatamy had always conducted himself soberly while in Brainerd's employ, but he initially showed no sign of concern for his own spiritual state. But then, one day in July 1744, after Brainerd preached with great fervor, something stirred in Tatamy's soul. The Indian began to engage in long conversations with Brainerd about spiritual matters, and his demeanor suddenly changed. Previously a carefree fellow, he was suddenly troubled night and day, unable to sleep, and complaining to Brainerd of an "impassable mountain" before him. "I must sink down to hell," Tatamy cried out one day, "because I never could do anything that was good."

David Brainerd could tell that God was at work on his Indian interpreter, Tunda Tatamy. Tatamy had always conducted himself soberly while in Brainerd's employ, but he initially showed no sign of concern for his own spiritual state. But then, one day in July 1744, after Brainerd preached with great fervor, something stirred in Tatamy's soul. The Indian began to engage in long conversations with Brainerd about spiritual matters, and his demeanor suddenly changed. Previously a carefree fellow, he was suddenly troubled night and day, unable to sleep, and complaining to Brainerd of an "impassable mountain" before him. "I must sink down to hell," Tatamy cried out one day, "because I never could do anything that was good."

The recognition of his own sinfulness marked Tatamy's moment of transformation. Just as suddenly as he had slipped into misery, he was reborn as a Christian convert. According to Brainerd, Tatamy became "another man, if not a new man," who would linger and preach to his Indian brethren long after Brainerd had finished his own sermons.

The tale Brainerd told of Tatamy's conversion follows the pattern of conversion narratives told by colonial men and women who were swept up in the Great Awakening, a wave of religious revivals in the 1740s. But Tatamy's conversion was different because he was an Indian, the first convert won by Brainerd during his work among the Delaware of the Lehigh Valley region. What did conversion to Christianity mean for someone like Tatamy? Was it a response to profound psychological pressures or a tactical decision aimed at appealing to his boss? And what did other Indians make of Christian converts like Tatamy? Did they follow his lead or scorn his decision to embrace the religion of their colonial neighbors? The life of Tatamy before and after his conversion offers some interesting clues for answering these questions.

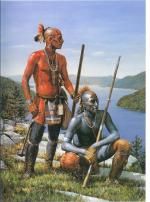

Tatamy was one of the Munsee Delaware, an Indian group that originally occupied the northern Delaware Valley, in modern New York and New Jersey. As a result of war and diseases associated with their seventeenth-century encounters with the Dutch traders of New Netherland, their numbers had dwindled considerably by the time of the English colonization of Pennsylvania. The Munsee that remained in eastern Pennsylvania by the 1740s were often referred to as the "Jersey" Delaware or "Forks" Delaware, a reference to their concentration around the confluence of the Lehigh and Delaware rivers.

Tatamy, born sometime around 1695, grew up in a world reshaped by European colonization. While some Delaware Indians elected to migrate west into the Susquehanna and Ohio Valleys so as to preserve their way of life, Tatamy was an example of others who chose acculturation and accommodation to their European neighbors. He first appears in Pennsylvania records as a messenger employed by the Penn family during the notorious Walking Purchase, which dispossessed many of the Indians living at the Forks of the Delaware.

Walking Purchase, which dispossessed many of the Indians living at the Forks of the Delaware.

In 1738, Tatamy petitioned the Pennsylvania government for permission to remain at the Forks, on the grounds that he was a "Christian," a claim that contradicts his supposed conversion a few years later. Perhaps in return for his previous service, and with the help of prominent settlers William Allen and Jeremiah Langhorne, Tatamy received a patent from the Penn family for 315 acres, making him the first private landowning Indian recognized by the Pennsylvania government.

During the mid-1740s, Tatamy worked as Brainerd's interpreter. After his conversion, he took the name "Moses," perhaps a biblical reference to Brainerd's hope that Tatamy's people would follow his lead into the Promised Land. That expectation never quite worked out. Although Tatamy continued to assist Brainerd and often preached to the Indians himself, Brainerd's harvest of Indian souls remained thin. Most of the Delaware he encountered simply preferred the spiritual path of their ancestors to the one offered by missionaries like Brainerd.

Recognizing his abilities as a go-between, Pennsylvania officials hired Tatamy to carry messages to the native people in their province and other colonies. In this capacity he worked with Irish fur trader George Croghan, German immigrant Conrad Weiser and Oneida sachem

Conrad Weiser and Oneida sachem  Shickellamy to help the people of two different worlds make sense of each other. Well-regarded for his honesty, Tatamy translated at treaty signings, explained the Indian ceremonies and customs that took place at these events to the white representatives, and explained white ways to Indian peoples.

Shickellamy to help the people of two different worlds make sense of each other. Well-regarded for his honesty, Tatamy translated at treaty signings, explained the Indian ceremonies and customs that took place at these events to the white representatives, and explained white ways to Indian peoples.

Tatamy's decision to identify himself as a Christian, landowning Indian helped secure his family for a while, but during the French and Indian War, his world began to unravel. He moved his family into New Jersey for safety, fearing for good reason that both western Delaware and his colonial neighbors might perceive him as an enemy. Disillusioned by the duplicity of the Europeans, Tatamy found comfort in liquor and often drank to excess. In July 1757, his anger and depression were compounded with grief when a settler shot and killed one of his sons simply because he looked suspicious. In late 1760, Moses Tunda Tatamy died.

Nine years after his death, Pennsylvania granted his son, Nicholas, a small parcel of land in recognition of his father's services to the province, but his family never recovered the wealth or reputation he had enjoyed during the 1740s, and Tatamy's descendants gradually disappeared from the Forks region. Today, the borough of Tatamy, located in Northampton County, bears his name.

"[Tatamy] is well fitted for his work, in regard to his acquaintance with the Indian and English languages, as well as with the manners of both nations, and in regard to his desire that the Indians should conform to the manners and customs of the English, and especially to their manner of living."

-David Brainerd

The missionary

The recognition of his own sinfulness marked Tatamy's moment of transformation. Just as suddenly as he had slipped into misery, he was reborn as a Christian convert. According to Brainerd, Tatamy became "another man, if not a new man," who would linger and preach to his Indian brethren long after Brainerd had finished his own sermons.

The tale Brainerd told of Tatamy's conversion follows the pattern of conversion narratives told by colonial men and women who were swept up in the Great Awakening, a wave of religious revivals in the 1740s. But Tatamy's conversion was different because he was an Indian, the first convert won by Brainerd during his work among the Delaware of the Lehigh Valley region. What did conversion to Christianity mean for someone like Tatamy? Was it a response to profound psychological pressures or a tactical decision aimed at appealing to his boss? And what did other Indians make of Christian converts like Tatamy? Did they follow his lead or scorn his decision to embrace the religion of their colonial neighbors? The life of Tatamy before and after his conversion offers some interesting clues for answering these questions.

Tatamy was one of the Munsee Delaware, an Indian group that originally occupied the northern Delaware Valley, in modern New York and New Jersey. As a result of war and diseases associated with their seventeenth-century encounters with the Dutch traders of New Netherland, their numbers had dwindled considerably by the time of the English colonization of Pennsylvania. The Munsee that remained in eastern Pennsylvania by the 1740s were often referred to as the "Jersey" Delaware or "Forks" Delaware, a reference to their concentration around the confluence of the Lehigh and Delaware rivers.

Tatamy, born sometime around 1695, grew up in a world reshaped by European colonization. While some Delaware Indians elected to migrate west into the Susquehanna and Ohio Valleys so as to preserve their way of life, Tatamy was an example of others who chose acculturation and accommodation to their European neighbors. He first appears in Pennsylvania records as a messenger employed by the Penn family during the notorious

In 1738, Tatamy petitioned the Pennsylvania government for permission to remain at the Forks, on the grounds that he was a "Christian," a claim that contradicts his supposed conversion a few years later. Perhaps in return for his previous service, and with the help of prominent settlers William Allen and Jeremiah Langhorne, Tatamy received a patent from the Penn family for 315 acres, making him the first private landowning Indian recognized by the Pennsylvania government.

During the mid-1740s, Tatamy worked as Brainerd's interpreter. After his conversion, he took the name "Moses," perhaps a biblical reference to Brainerd's hope that Tatamy's people would follow his lead into the Promised Land. That expectation never quite worked out. Although Tatamy continued to assist Brainerd and often preached to the Indians himself, Brainerd's harvest of Indian souls remained thin. Most of the Delaware he encountered simply preferred the spiritual path of their ancestors to the one offered by missionaries like Brainerd.

Recognizing his abilities as a go-between, Pennsylvania officials hired Tatamy to carry messages to the native people in their province and other colonies. In this capacity he worked with Irish fur trader George Croghan, German immigrant

Tatamy's decision to identify himself as a Christian, landowning Indian helped secure his family for a while, but during the French and Indian War, his world began to unravel. He moved his family into New Jersey for safety, fearing for good reason that both western Delaware and his colonial neighbors might perceive him as an enemy. Disillusioned by the duplicity of the Europeans, Tatamy found comfort in liquor and often drank to excess. In July 1757, his anger and depression were compounded with grief when a settler shot and killed one of his sons simply because he looked suspicious. In late 1760, Moses Tunda Tatamy died.

Nine years after his death, Pennsylvania granted his son, Nicholas, a small parcel of land in recognition of his father's services to the province, but his family never recovered the wealth or reputation he had enjoyed during the 1740s, and Tatamy's descendants gradually disappeared from the Forks region. Today, the borough of Tatamy, located in Northampton County, bears his name.

Beyond the Marker