![header=[Marker Text] body=[A great Indian highway from Six Nations country, New York, to the Catawba country in the Carolinas. It made its way through the Allegheny Mountains by following the Susquehanna and Juniata valleys. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-208-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h5a5-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Warriors Path

Region:

Poconos / Endless Mountains

County:

Bradford

Marker Location:

GAR Hwy. (US 6), 1.3 miles N of Wyalusing

Dedication Date:

March 15, 1949

Behind the Marker

Witham Marshe traveled to Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1744 as part of a Maryland delegation to an Indian treaty. In his journal, he detailed the arrival of the Iroquois Indians with whom the colonial delegates would be conducting business:

The sights and sounds of that particular occasion must have elicited a variety of feelings from Marshe and other colonists witnessing their first Indian treaty. A certain amount of dread may have arisen from seeing so many well-armed Indians walking into a small colonial town on an exposed frontier. But that feeling may have been checked by the sight of Indian women and children, who clearly would not have been part of a war party. And what of the song sung in an unintelligible language to its intended listeners? Did Marshe find it pleasing when he heard it, or only after someone translated its message of peace and friendship to him?

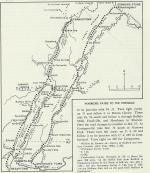

Marshe may have been surprised by what he witnessed in Lancaster, but for the Iroquois Indians he met there, the route and purpose of their trip was quite familiar. Long before Europeans arrived in North America, Indians created a network of land and water routes that connected distant communities and cultures in trade, diplomacy, warfare, and migration. The Warriors Path ran north-to-south from its origins in central New York through the middle of Pennsylvania, following the north branch of the Susquehanna River until its juncture with the west branch at the Indian village of Shamokin (Sunbury), at which point it veered southwest through present-day Huntingdon and Bedford before crossing the Potomac River near Cumberland, Maryland.

From the Potomac, the Warriors Path continued south into the Virginia and Carolinas backcountry, along the eastern edge of the Appalachian Mountains. It was one of the longest and most heavily traveled native land routes in eastern North America, connecting Indian peoples over hundreds of miles.

The Iroquois Indians who traveled to Lancaster in 1744 would have followed the Warriors Path for the first leg of their trip: from their homelands in modern central New York to the village of Shamokin at the juncture of the north and west branches of the Susquehanna. From there, they would have followed another path southeast toward Lancaster. Europeans commonly gave the name "Warriors Path" to any route traveled by Indian war parties, but as Marshe's experiences attest, this name could be misleading, because not everyone who traveled on the Warrior's Path was intent on making war.

Indian chiefs such as Canasatego followed such routes to attend councils with Indian and colonial leaders. Indian hunters and colonial fur traders followed such routes in pursuit of game and pelts. Entire Indian communities -men, women, and children, old and young - would follow such paths to seasonal camps, to visit distant kin, or to take advantage of the food, drink, and material goods offered at treaty conferences such as the one Marshe attended.

During the 1700s, some Indian groups displaced by warfare or colonization along the southern frontier used the Warriors Path to migrate north in search of new homelands. One such group, the Tuscaroras, was an Iroquoian-speaking nation from North Carolina. After warring with that colony and other Native Americans in the 1710s, the Tuscaroras followed the Warriors Path into the northern Susquehanna Valley and became the sixth nation in the Iroquois Confederacy.

As European settlers pushed west, the Warriors Path shifted west as well. Indians and colonial governments negotiated agreements at treaty conferences, such as the one in Lancaster in 1744, that were intended to keep war parties away from colonial homesteads. The Iroquois, however, always insisted on maintaining an open route through Pennsylvania so that they could war with the Catawbas and Cherokees, southeastern Indian nations with whom they had been enemies for generations.

By the mid-1700s, European immigrants to North America were arriving in droves in Philadelphia and trekking westward across the Susquehanna River, where they turned south and followed the Warriors Path into the backcountry of Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. They traveled the same route as Indian warriors and diplomats, only these new arrivals renamed the route the "The Great Wagon Road," a reference to the many wagons made in Pennsylvania that helped carry them and their belongings to their new homes.

As this renaming suggests, these frontier settlers liked to think of themselves as hardy pioneers venturing into a trackless wilderness, but they were literally following in the footsteps of Indians who had already blazed a trail for them.

"During our dinner, the deputies of the Six Nations [Iroquois], with their followers and attendants, to the number of 252, arrived in town. Several of their squaws, or wives, with some small children, rode on horseback, which is very unusual for them. They brought their fire-arms and bows and arrows, as well as tomahawks. A great concourse of people followed them. They marched in very good order, with Cannasateego [Canasatego], one of the Onondaga chiefs, at their head; who, when he came near to the court-house wherein we were dining, sung, in the Indian language, a song, inviting us to a renewal of all treaties heretofore made, and that [are] now to be made."

The sights and sounds of that particular occasion must have elicited a variety of feelings from Marshe and other colonists witnessing their first Indian treaty. A certain amount of dread may have arisen from seeing so many well-armed Indians walking into a small colonial town on an exposed frontier. But that feeling may have been checked by the sight of Indian women and children, who clearly would not have been part of a war party. And what of the song sung in an unintelligible language to its intended listeners? Did Marshe find it pleasing when he heard it, or only after someone translated its message of peace and friendship to him?

Marshe may have been surprised by what he witnessed in Lancaster, but for the Iroquois Indians he met there, the route and purpose of their trip was quite familiar. Long before Europeans arrived in North America, Indians created a network of land and water routes that connected distant communities and cultures in trade, diplomacy, warfare, and migration. The Warriors Path ran north-to-south from its origins in central New York through the middle of Pennsylvania, following the north branch of the Susquehanna River until its juncture with the west branch at the Indian village of Shamokin (Sunbury), at which point it veered southwest through present-day Huntingdon and Bedford before crossing the Potomac River near Cumberland, Maryland.

From the Potomac, the Warriors Path continued south into the Virginia and Carolinas backcountry, along the eastern edge of the Appalachian Mountains. It was one of the longest and most heavily traveled native land routes in eastern North America, connecting Indian peoples over hundreds of miles.

The Iroquois Indians who traveled to Lancaster in 1744 would have followed the Warriors Path for the first leg of their trip: from their homelands in modern central New York to the village of Shamokin at the juncture of the north and west branches of the Susquehanna. From there, they would have followed another path southeast toward Lancaster. Europeans commonly gave the name "Warriors Path" to any route traveled by Indian war parties, but as Marshe's experiences attest, this name could be misleading, because not everyone who traveled on the Warrior's Path was intent on making war.

Indian chiefs such as Canasatego followed such routes to attend councils with Indian and colonial leaders. Indian hunters and colonial fur traders followed such routes in pursuit of game and pelts. Entire Indian communities -men, women, and children, old and young - would follow such paths to seasonal camps, to visit distant kin, or to take advantage of the food, drink, and material goods offered at treaty conferences such as the one Marshe attended.

During the 1700s, some Indian groups displaced by warfare or colonization along the southern frontier used the Warriors Path to migrate north in search of new homelands. One such group, the Tuscaroras, was an Iroquoian-speaking nation from North Carolina. After warring with that colony and other Native Americans in the 1710s, the Tuscaroras followed the Warriors Path into the northern Susquehanna Valley and became the sixth nation in the Iroquois Confederacy.

As European settlers pushed west, the Warriors Path shifted west as well. Indians and colonial governments negotiated agreements at treaty conferences, such as the one in Lancaster in 1744, that were intended to keep war parties away from colonial homesteads. The Iroquois, however, always insisted on maintaining an open route through Pennsylvania so that they could war with the Catawbas and Cherokees, southeastern Indian nations with whom they had been enemies for generations.

By the mid-1700s, European immigrants to North America were arriving in droves in Philadelphia and trekking westward across the Susquehanna River, where they turned south and followed the Warriors Path into the backcountry of Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. They traveled the same route as Indian warriors and diplomats, only these new arrivals renamed the route the "The Great Wagon Road," a reference to the many wagons made in Pennsylvania that helped carry them and their belongings to their new homes.

As this renaming suggests, these frontier settlers liked to think of themselves as hardy pioneers venturing into a trackless wilderness, but they were literally following in the footsteps of Indians who had already blazed a trail for them.