![header=[Marker Text] body=[Recognized as the inventor of the first sleeping car in the U.S. for use of travelers. The car, "Chambersburg," was operated as early as 1838 between Harrisburg and Chambersburg. He lies buried in graveyard at rear of church.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-1D3-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0b2d9-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Philip Berlin

Region:

Hershey/Gettysburg/Dutch Country Region

County:

Franklin

Marker Location:

W. Washington St. at Lutheran Church, Chambersburg

Dedication Date:

August 10, 1953

Behind the Marker

In the 1830s, twenty-five years before George Pullman built his first sleeping car and nearly a century before travelers took for granted the nation's 8,000 sleeping cars, the multi-night trip between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia was long and uncomfortable. From Pittsburgh, passengers first took a stagecoach to Chambersburg, where they arrived about midnight. Those who were anxious to continue on to Philadelphia then boarded the 1 a.m. train to Harrisburg, where they connected with the morning train to Philadelphia. Inspired by a conversation with a weary traveler who had just endured the long, jolting thirty-six hours on the stage from Pittsburgh, Philip Berlin, a director of the  Cumberland Valley Railroad (CVRR), saw the need for a sleeper car - and built it.

Cumberland Valley Railroad (CVRR), saw the need for a sleeper car - and built it.

Berlin was born on the Atlantic Ocean in 1780, while his German parents were immigrating to Pennsylvania. The Berlin family settled among a growing German and Scotch-Irish community in the Cumberland Valley of south-central Pennsylvania. As a youth, Berlin established himself in Chambersburg as an excellent wagon maker, and then became a successful merchant, operating three dry goods and grocery stores for more than forty years. In Chambersburg, Berlin also became director of the Poor-House, a Franklin County commissioner, and a state legislator, from 1827 to 1828.

The CVRR connected the Susquehanna and Potomac rivers by rail through the rich Cumberland Valley of south-central Pennsylvania. Construction began in 1836, and some fifty-two miles of line were completed between Harrisburg and Chambersburg by November of 1837. Regularly scheduled service began in February, 1838.

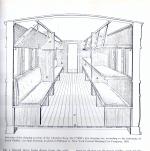

Soon afterward, Berlin contracted with railroad-car builder Philip Imlay of Philadelphia to build cars for the CVRR, including a novel thirty-eight-foot-long car called the Chambersburg, which was divided into two sections. One end was a coach section with bench-style seating that held as many as forty passengers. At the opposite end were three sleeping-car berth sections, separated by partitions, two for men and one for women.

Each of the men's sections was fitted with nineteen-inch-wide berths that were arranged three tiers high along each side of the car. The women's section contained only a single level of double-width berths. The berths consisted of upholstered boards that were held firmly in place by leather straps, which folded back against the wall to create side benches for daytime travel. Each passenger was issued a coverlet and a round pillow; no extra charge was levied for riding in the berths. As in the regular day coaches of the era, a stove provided heat in winter and tallow candles brightened it by night.

Within two years, business grew so much that CVRR ordered a second sleeper, named Carlisle, which CVRR carpenter Jacob Shaffer converted from a day coach in the road's Chambersburg shops.

Sleeping-car design remained relatively unimproved until 1864, when George Pullman of Chicago developed his version. The idea of multiplying the effectiveness of one's time by traveling while sleeping was hugely attractive to speed-hungry Americans. By the 1920s, the Pullman Company was operating 8,000 sleeping cars every night on the railroads of America. Much of the space sold by Pullman went to business travelers, to whom the railroads catered with their overnight schedules. Executives or sales people could spend a business day in one city, then wrap up their affairs in time to catch an evening overnight train to another city 300 to 500 miles away. When they arrived at the destination city in the morning, they were ready for another round of appointments or sales calls at that location.

Sandwiched between East Coast cities and the Midwest, Pennsylvania saw the nightly passage of dozens upon dozens of first-class east-west sleeper trains on the four trunk-line railroads that crossed the state. Each competed to provide the most luxurious travel experience: the flagships of their fleets were the Twentieth Century Limited of the New York Central (New York-Buffalo-Erie-Chicago), the Broadway Limited of the Pennsylvania (New York-Philadelphia-Pittsburgh-Chicago), the Capitol Limited of the Baltimore and Ohio (Washington-Pittsburgh-Chicago), and the Erie Limited of the Erie Railroad (Jersey City, N.J.-Chicago). Every U.S. president from the 1870s through Eisenhower rode sleeping cars - often, they were presidential private cars - when they traveled for official business or to campaign for election.

To protect his monopoly of the American sleeping car industry, Pullman, who built his own sleepers at a massive plant near Chicago, regularly sued his competitors for infringement on his sleeper car patents. Defendants consistently secured evidence from CVRR officials to show that the devices in question had been in common use long before Pullman had developed his version of them. In this way, Philip Berlin's early innovation helped advance the comfort of rail travel in America. Although business travelers deserted the extensive network of Pullman service when commercial jetliners came on the scene in the 1950s, Amtrak continues to offer sleeping-car space on many of its long-distance trains.

Berlin was born on the Atlantic Ocean in 1780, while his German parents were immigrating to Pennsylvania. The Berlin family settled among a growing German and Scotch-Irish community in the Cumberland Valley of south-central Pennsylvania. As a youth, Berlin established himself in Chambersburg as an excellent wagon maker, and then became a successful merchant, operating three dry goods and grocery stores for more than forty years. In Chambersburg, Berlin also became director of the Poor-House, a Franklin County commissioner, and a state legislator, from 1827 to 1828.

The CVRR connected the Susquehanna and Potomac rivers by rail through the rich Cumberland Valley of south-central Pennsylvania. Construction began in 1836, and some fifty-two miles of line were completed between Harrisburg and Chambersburg by November of 1837. Regularly scheduled service began in February, 1838.

Soon afterward, Berlin contracted with railroad-car builder Philip Imlay of Philadelphia to build cars for the CVRR, including a novel thirty-eight-foot-long car called the Chambersburg, which was divided into two sections. One end was a coach section with bench-style seating that held as many as forty passengers. At the opposite end were three sleeping-car berth sections, separated by partitions, two for men and one for women.

Each of the men's sections was fitted with nineteen-inch-wide berths that were arranged three tiers high along each side of the car. The women's section contained only a single level of double-width berths. The berths consisted of upholstered boards that were held firmly in place by leather straps, which folded back against the wall to create side benches for daytime travel. Each passenger was issued a coverlet and a round pillow; no extra charge was levied for riding in the berths. As in the regular day coaches of the era, a stove provided heat in winter and tallow candles brightened it by night.

Within two years, business grew so much that CVRR ordered a second sleeper, named Carlisle, which CVRR carpenter Jacob Shaffer converted from a day coach in the road's Chambersburg shops.

Sleeping-car design remained relatively unimproved until 1864, when George Pullman of Chicago developed his version. The idea of multiplying the effectiveness of one's time by traveling while sleeping was hugely attractive to speed-hungry Americans. By the 1920s, the Pullman Company was operating 8,000 sleeping cars every night on the railroads of America. Much of the space sold by Pullman went to business travelers, to whom the railroads catered with their overnight schedules. Executives or sales people could spend a business day in one city, then wrap up their affairs in time to catch an evening overnight train to another city 300 to 500 miles away. When they arrived at the destination city in the morning, they were ready for another round of appointments or sales calls at that location.

Sandwiched between East Coast cities and the Midwest, Pennsylvania saw the nightly passage of dozens upon dozens of first-class east-west sleeper trains on the four trunk-line railroads that crossed the state. Each competed to provide the most luxurious travel experience: the flagships of their fleets were the Twentieth Century Limited of the New York Central (New York-Buffalo-Erie-Chicago), the Broadway Limited of the Pennsylvania (New York-Philadelphia-Pittsburgh-Chicago), the Capitol Limited of the Baltimore and Ohio (Washington-Pittsburgh-Chicago), and the Erie Limited of the Erie Railroad (Jersey City, N.J.-Chicago). Every U.S. president from the 1870s through Eisenhower rode sleeping cars - often, they were presidential private cars - when they traveled for official business or to campaign for election.

To protect his monopoly of the American sleeping car industry, Pullman, who built his own sleepers at a massive plant near Chicago, regularly sued his competitors for infringement on his sleeper car patents. Defendants consistently secured evidence from CVRR officials to show that the devices in question had been in common use long before Pullman had developed his version of them. In this way, Philip Berlin's early innovation helped advance the comfort of rail travel in America. Although business travelers deserted the extensive network of Pullman service when commercial jetliners came on the scene in the 1950s, Amtrak continues to offer sleeping-car space on many of its long-distance trains.

Beyond the Marker