![header=[Marker Text] body=[Modernist painter and photographer, known for a seemingly impersonal, machine-inspired style called precisionism. Subjects included factories, skyscrapers, and Bucks County barns. He rented the Worthington House, 1910-26, and here he did important early work. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-1A3-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0a9u7-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Charles Sheeler

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Bucks

Marker Location:

39 Mercer Ave. at Center St., Doylestown

Dedication Date:

May 29, 1999

Behind the Marker

If you visit The Art Institute of Chicago, make sure you see Charles Sheeler's unusual 1943 self-portrait entitled "The Artist Looks at Nature." In it, an elderly man paints a small enclosed room, while observing what seems to be the most unnatural "nature" you can imagine: manicured lawns without flowers or trees, segmented by equally stark, simple walls. The small painting resembles another one that Sheeler executed twelve years earlier entitled "View of New York" (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Instead of the expected skyline, Sheeler offers us a tiny room in a small apartment in which many city residents live.

In his self-portrait, Sheeler encapsulated his life's work, questioning the very nature of "nature." He included as "among the experiences of artists from which their work derives, the miracle of spring - the first leaf buds and with them the reassurance of life making a new beginning. The trees in mid-summer with their opulence of celebration [And] the unbelievable swan-song of autumn - the fragrance of burning leaves in the air." Then, suddenly, autumn is not followed by winter, but by "the man-made architecture inlaid in these environments to serve its several purposes." In this startling final sentence, in which nature as bucolic and refreshing is suddenly called up short by a nature that includes buildings, Sheeler summarized his work. "All Nature has an underlying abstract structure and it is within the province of the artist to search for it and to select and rearrange the forms for the enhancement of his design."

Born in Philadelphia, Sheeler attended the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (the present University of the Arts) for three years after his graduation from high school. He then attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. In the first ten years of the twentieth century he studied there with William Merritt Chase and then went to Europe, but was disenchanted with the artistic styles then in vogue. "I had to bail out, as I've called it for another ten years, before I really got started in a new direction," he later wrote. "There was no more possible justice of the [posing human] model or to go out and paint a landscape."

Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. In the first ten years of the twentieth century he studied there with William Merritt Chase and then went to Europe, but was disenchanted with the artistic styles then in vogue. "I had to bail out, as I've called it for another ten years, before I really got started in a new direction," he later wrote. "There was no more possible justice of the [posing human] model or to go out and paint a landscape."

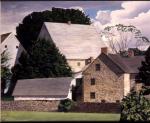

He then moved to Doylestown in Bucks County with his good friend and fellow artist Morton Schamberg (Sheeler did not marry until three years after Schamberg's early death in 1918) where he began to paint in the manner of the Cubist school associated with Pablo Picasso, and to experiment with photography. Sheeler considered the influence of the geometrical patterns of Bucks County architecture as a turning point in his work, as it would be two decades later for photographer Aaron Siskind.

Aaron Siskind.

In Sheeler's work, buildings and landscapes were rendered as objective geometrical forms, monochromatic colors, with no hint of weather or time of day. As Sheeler wrote in a laudatory exhibition review of ancient Greek art that may be applied to his own, its "geometric basis was the internal structure around which was built the objective aspect of nature. . . . The profound understanding of the harmony of rhythms and proportions enabled the Greeks to create sculptures of the smallest dimensions which have the grandeur and scale of works of heroic proportions."

works of heroic proportions."

The austere colonial beauty of Bucks County barns and houses and the settlement at Ephrata inspired much of Sheeler's work before he moved to New York City in 1919. His paintings and photographs reflected the geometrical patterns of barns and interiors that he later extended on a larger scale. He was welcomed and praised by the avant-garde of the art world, showing six paintings at the famous New York Armory Show of 1913. Among his patrons were Walter and Louise Arensberg and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, who donated much of his work to New York's Museum of Modern Art. He moved to South Salem in rural upstate New York in 1926.

To earn money, Sheeler took up took up commercial photography for Vogue, Vanity Fair, and other magazines, and used both paintings and photographs in the same style to create advertisements for the Tennessee Valley Authority, Ford Motor Company, and other corporations. He worked briefly on the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg and for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and exhibited his work throughout the country at major museums. After World War II, he taught at the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and served as a curator at the Currier Gallery in Manchester, New Hampshire. He died in Dobbs Ferry, New York, six years after he suffered a stroke that left him unable to paint.

took up commercial photography for Vogue, Vanity Fair, and other magazines, and used both paintings and photographs in the same style to create advertisements for the Tennessee Valley Authority, Ford Motor Company, and other corporations. He worked briefly on the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg and for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and exhibited his work throughout the country at major museums. After World War II, he taught at the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and served as a curator at the Currier Gallery in Manchester, New Hampshire. He died in Dobbs Ferry, New York, six years after he suffered a stroke that left him unable to paint.

Although cultural critic Constance Rourke, in the first important biography of Sheeler (1938), stressed that he successfully conveyed the power and glory of the modern veneration of the industrial machine - "Our factories are our substitute for religious expression" - other writers found his work "inhuman," for eliminating "the mind and the heart of the artist which make him see the world . . . through his own experience."

In a sense, Sheeler's work foreshadowed that of Pittsburgh native Andy Warhol, who also moved to New York, and reproduced soup cans and images of pop icons such as Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy that appear "objective." But just as critics have found both tragedy and comedy in Warhol's images (there is no "real" Marilyn, only a repeatedly reproduced image), they have also realized the complexity of Sheeler's art. His urban landscapes may be viewed either as appreciations or criticisms of the increasingly man-made society and colossal geometric architecture which characterize modern America.

In his self-portrait, Sheeler encapsulated his life's work, questioning the very nature of "nature." He included as "among the experiences of artists from which their work derives, the miracle of spring - the first leaf buds and with them the reassurance of life making a new beginning. The trees in mid-summer with their opulence of celebration [And] the unbelievable swan-song of autumn - the fragrance of burning leaves in the air." Then, suddenly, autumn is not followed by winter, but by "the man-made architecture inlaid in these environments to serve its several purposes." In this startling final sentence, in which nature as bucolic and refreshing is suddenly called up short by a nature that includes buildings, Sheeler summarized his work. "All Nature has an underlying abstract structure and it is within the province of the artist to search for it and to select and rearrange the forms for the enhancement of his design."

Born in Philadelphia, Sheeler attended the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (the present University of the Arts) for three years after his graduation from high school. He then attended the

He then moved to Doylestown in Bucks County with his good friend and fellow artist Morton Schamberg (Sheeler did not marry until three years after Schamberg's early death in 1918) where he began to paint in the manner of the Cubist school associated with Pablo Picasso, and to experiment with photography. Sheeler considered the influence of the geometrical patterns of Bucks County architecture as a turning point in his work, as it would be two decades later for photographer

In Sheeler's work, buildings and landscapes were rendered as objective geometrical forms, monochromatic colors, with no hint of weather or time of day. As Sheeler wrote in a laudatory exhibition review of ancient Greek art that may be applied to his own, its "geometric basis was the internal structure around which was built the objective aspect of nature. . . . The profound understanding of the harmony of rhythms and proportions enabled the Greeks to create sculptures of the smallest dimensions which have the grandeur and scale of

The austere colonial beauty of Bucks County barns and houses and the settlement at Ephrata inspired much of Sheeler's work before he moved to New York City in 1919. His paintings and photographs reflected the geometrical patterns of barns and interiors that he later extended on a larger scale. He was welcomed and praised by the avant-garde of the art world, showing six paintings at the famous New York Armory Show of 1913. Among his patrons were Walter and Louise Arensberg and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, who donated much of his work to New York's Museum of Modern Art. He moved to South Salem in rural upstate New York in 1926.

To earn money, Sheeler took up

Although cultural critic Constance Rourke, in the first important biography of Sheeler (1938), stressed that he successfully conveyed the power and glory of the modern veneration of the industrial machine - "Our factories are our substitute for religious expression" - other writers found his work "inhuman," for eliminating "the mind and the heart of the artist which make him see the world . . . through his own experience."

In a sense, Sheeler's work foreshadowed that of Pittsburgh native Andy Warhol, who also moved to New York, and reproduced soup cans and images of pop icons such as Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy that appear "objective." But just as critics have found both tragedy and comedy in Warhol's images (there is no "real" Marilyn, only a repeatedly reproduced image), they have also realized the complexity of Sheeler's art. His urban landscapes may be viewed either as appreciations or criticisms of the increasingly man-made society and colossal geometric architecture which characterize modern America.