Chapter Four: Labor Strikes and Mine Disasters

They called them "damps." That's the name mine workers gave to various gases in coal mines. In September 1869, 110 men and boys were killed in the Avondale colliery in Luzerne County as a result of an underground mine fire ignited by mine gas. It was the deadliest disaster in the history of anthracite mining.

The Avondale Mine Disaster was a horrific event that awoke the public and the state legislature to the dangers mine workers knew well and had been trying to alleviate. The Workingmen's Benevolent Association, a local organization for mine workers, had petitioned the state for greater safety measures just months before the disaster. But it took the Avondale deaths to get a law enacted that prohibited coal operators from building a coal breaker directly atop a mine opening, and required management to have two openings to mine workings.

Avondale Mine Disaster was a horrific event that awoke the public and the state legislature to the dangers mine workers knew well and had been trying to alleviate. The Workingmen's Benevolent Association, a local organization for mine workers, had petitioned the state for greater safety measures just months before the disaster. But it took the Avondale deaths to get a law enacted that prohibited coal operators from building a coal breaker directly atop a mine opening, and required management to have two openings to mine workings.

Limited in its scope and widely ignored, the Mining Safety Law of 1870 had little impact, and mining hazards continued to be a widespread problem. "Robbing the pillars" was another example of dangerous practices encouraged by management. As miners excavated a "room," they left pillars of coal standing to help support the roof overhead; when all of the coal had been removed from a room, managers ordered the workers to remove remaining pillars. When the roof started "pressing" (down), sometimes it would emit a crackling sound. Sometimes it just fell.

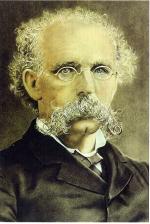

Terence V. Powderly, future head of the Knights of Labor, reported that hearing union activists talk about the deaths at Avondale convinced him to devote his life to working as an organizer. Powderly, who also served as mayor of Scranton in the 1870s, was a political unionist. He believed in working for union goals through the democratic political process and opposed the use of strikes as a tool in collective bargaining. This commitment and his willingness to broaden the labor coalition to unskilled workers, many of whom were recent immigrants, made him a revolutionary figure in the history of the American labor movement.

Terence V. Powderly, future head of the Knights of Labor, reported that hearing union activists talk about the deaths at Avondale convinced him to devote his life to working as an organizer. Powderly, who also served as mayor of Scranton in the 1870s, was a political unionist. He believed in working for union goals through the democratic political process and opposed the use of strikes as a tool in collective bargaining. This commitment and his willingness to broaden the labor coalition to unskilled workers, many of whom were recent immigrants, made him a revolutionary figure in the history of the American labor movement.

The diversity of coal miners' ethnicity, religions, and languages made it difficult for them to organize. Avondale, in fact, had been blamed on the Irish, who had been angry about consistently receiving the lowliest and most dangerous jobs at the colliery. In part, this suspicion of the Irish was due to the secretive Molly Maguires, who had been accused of murdering mine managers and were executed by hanging in

Molly Maguires, who had been accused of murdering mine managers and were executed by hanging in  Schuylkill and

Schuylkill and  Carbon counties.

Carbon counties.

The blame for subsequent rock falls or dynamite explosions that fatally injured miners was laid upon the Irish, then the Italians, and then the Slovaks. A belief in Anglo-American superiority was widespread in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and this prejudice was used by mine owners to divide the workers in order to stall something else that management opposed: unions.

Two more horrific events near the turn of the twentieth century helped unify mine workers and inspire their leaders. The first was the Twin Shaft Disaster of 1896. Fifty-eight men died during a mine cave-in at a colliery in Luzerne County. Miners in the region pointed to the ongoing safety hazards that they faced and the negligence of mine operators as a fundamental justification for unionization. Other issues that executives were unwilling to negotiate included day-to-day leases of company homes, the practice of "docking" a percentage of the value of coal for its impurities, automatic fee deductions from workers' pay for the company doctor, and wages that had dropped or remained stagnant for years.

Twin Shaft Disaster of 1896. Fifty-eight men died during a mine cave-in at a colliery in Luzerne County. Miners in the region pointed to the ongoing safety hazards that they faced and the negligence of mine operators as a fundamental justification for unionization. Other issues that executives were unwilling to negotiate included day-to-day leases of company homes, the practice of "docking" a percentage of the value of coal for its impurities, automatic fee deductions from workers' pay for the company doctor, and wages that had dropped or remained stagnant for years.

The next year, 1897, a contingent of sheriff's deputies fired upon an unarmed procession of striking mine workers who were marching between the patch towns of Harwood and Lattimer in Luzerne County. The deputies killed nineteen and wounded thirty-six people in what became known as the Lattimer Massacre. The dead and wounded workers were immigrants from Eastern Europe who protested an "alien tax" imposed by the General Assembly, and were proponents of better conditions in their mines. Both the Lattimer Massacre and the Twin Shaft Disaster resulted in greater unity among mine workers who began to listen to labor leader John Mitchell's message: unite.

Lattimer Massacre. The dead and wounded workers were immigrants from Eastern Europe who protested an "alien tax" imposed by the General Assembly, and were proponents of better conditions in their mines. Both the Lattimer Massacre and the Twin Shaft Disaster resulted in greater unity among mine workers who began to listen to labor leader John Mitchell's message: unite.

By 1900, establishing a grievance procedure throughout the anthracite fields was a major strike issue and the efforts of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) to organize anthracite workers gained ground. The great labor advocate Mother Jones led 2,000 wives, children and miners in a march in Schuylkill County, articulating the injustices felt across the fields from workers who produced so much and got so little in return.

Mother Jones led 2,000 wives, children and miners in a march in Schuylkill County, articulating the injustices felt across the fields from workers who produced so much and got so little in return.

The tension between mine owners and workers crested during the long Anthracite Strike of 1902. Until this point, the UMWA had represented many bituminous mine workers in western Pennsylvania, but anthracite miners had remained mostly non-union, fragmented by different work experiences between the fields and by companies that pitted one group against another. However, mine disasters and labor actions that produced hard fought concessions had taught colliery workers that they held much in common, and that in order to secure a living wage and better conditions for themselves and their families, they had to hold together for as long as it took. The strike of 1902 demonstrated their resolve.

Anthracite Strike of 1902. Until this point, the UMWA had represented many bituminous mine workers in western Pennsylvania, but anthracite miners had remained mostly non-union, fragmented by different work experiences between the fields and by companies that pitted one group against another. However, mine disasters and labor actions that produced hard fought concessions had taught colliery workers that they held much in common, and that in order to secure a living wage and better conditions for themselves and their families, they had to hold together for as long as it took. The strike of 1902 demonstrated their resolve.

From March to October 1902, 150,000 workers stayed out of the mines and in many ways steered the union to insist on their demands to ensure a fairer workplace. With the leadership of UMWA president John Mitchell, future Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson, and the

William B. Wilson, and the  Rev. John J. Curran, the striking workers forced the federal government to intervene on their behalf.

Rev. John J. Curran, the striking workers forced the federal government to intervene on their behalf.  The Anthracite Strike Commission, an outside arbitration group that President Theodore Roosevelt had pressured the coal operators to accept, heard weeks of testimony from miners, their wives, coal community leaders, and mine management on issues that had divided labor and management for so long.

The Anthracite Strike Commission, an outside arbitration group that President Theodore Roosevelt had pressured the coal operators to accept, heard weeks of testimony from miners, their wives, coal community leaders, and mine management on issues that had divided labor and management for so long.

In the end, the Commission granted some of the workers' demands, yet was reluctant to disrupt the "business of mining" by empowering workers. Moreover, one result miners sought in the Great Strike of 1902 was not gained: company executives did not have to recognize the UMWA as an official union.

Future conflicts were inevitable, as were additional mine disasters. In 1911, the horrible Anthracite Mine Disaster killed seventy-two miners. The industry continued to grow in the first decades of the 20th century, producing nearly 100 million tons in 1917. Soaring inflation during World War I, unresolved worker grievances, and a 1922 strike that, for the first time, shut down both the anthracite and bituminous mining industries left workers feeling bitter towards UMWA leaders, who had gained only meager concessions. They challenged UMWA President John L. Lewis' leadership and his concern for circumstances in the anthracite fields, notably the increasing practice of "contract mining." Railroad companies had begun leasing their mines to contracting companies that were paid by tonnage.

Anthracite Mine Disaster killed seventy-two miners. The industry continued to grow in the first decades of the 20th century, producing nearly 100 million tons in 1917. Soaring inflation during World War I, unresolved worker grievances, and a 1922 strike that, for the first time, shut down both the anthracite and bituminous mining industries left workers feeling bitter towards UMWA leaders, who had gained only meager concessions. They challenged UMWA President John L. Lewis' leadership and his concern for circumstances in the anthracite fields, notably the increasing practice of "contract mining." Railroad companies had begun leasing their mines to contracting companies that were paid by tonnage.

Under the new contract operators drove the men hard, firing at whim and cutting corners on equipment and safety regulations in their extraction of anthracite. During the Great Depression, a rival organization, the United Anthracite Miners of Pennsylvania (UAMP), arose and tried to meet the needs of anthracite workers in a dying industry.

By the 1920s and 1930s, consumers of anthracite began shifting to oil, natural gas and electricity. Stubborn coal executives, still locked into their hostile battle with labor, held on to their profits by reducing labor costs, leasing operations to small non-union operators, and did not develop new markets or technologies for anthracite. As the Great Depression shook the country and the world, northeastern Pennsylvania had already fallen on hard times.

The decline of anthracite can be measured in tons: the Pennsylvania fields produced nearly 100 million tons in 1917 and only 69 million in 1930. By the late 1940s, only 80,000 worked in the mines. As the industry continued its long decline, some men got three days of work a week; many got none. The older, more skilled miners (usually with larger families to support) were fired first because they earned more.

Anthracite workers and the UAMP called for "work equalization," in which companies would spread out the work across their mines rather than operating only one colliery where the coal was easiest to reach. The companies and the UMWA opposed this and other reforms. "Unemployed councils," another grass-roots initiative with thousands of participants, provided food and aid to the needy and called for unemployment insurance legislation.

Pressure nationwide pushed the Roosevelt administration, in 1935, to include unemployment compensation and a pension system in the Social Security Act. Social activism and militancy grew; there were violent clashes between workers and owners, and the UAMP president was killed with a package bomb. While unemployed miners dug pits for "bootleg mining," their wives and daughters endured exploitation by garment factory owners to help their families survive, earning six dollars pay for a 60-hour work week.

"bootleg mining," their wives and daughters endured exploitation by garment factory owners to help their families survive, earning six dollars pay for a 60-hour work week.  Min Matheson of the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union led them to demand, as their fathers and brothers had done before them, a voice in the management of their work and their welfare.

Min Matheson of the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union led them to demand, as their fathers and brothers had done before them, a voice in the management of their work and their welfare.

The symbolic end of the anthracite coal era came in 1959, when the Knox Mine Disaster occurred at the Knox Coal Company's River Slope mine near Pittston in Luzerne County. The larger Pennsylvania Coal Company leased the mine to Knox, a company founded by a leading organized crime figure. Collusion between the Knox Coal Company, the UMWA, and organized crime led to illegal practices that had brought a mine tunnel much closer to the bed of the Susquehanna River than allowed by state regulations. When the river crashed through the mine's ceiling, forty-five workers were trapped; twelve died. This catastrophic flooding ended deep mining in much of the northern anthracite region.

Knox Mine Disaster occurred at the Knox Coal Company's River Slope mine near Pittston in Luzerne County. The larger Pennsylvania Coal Company leased the mine to Knox, a company founded by a leading organized crime figure. Collusion between the Knox Coal Company, the UMWA, and organized crime led to illegal practices that had brought a mine tunnel much closer to the bed of the Susquehanna River than allowed by state regulations. When the river crashed through the mine's ceiling, forty-five workers were trapped; twelve died. This catastrophic flooding ended deep mining in much of the northern anthracite region.

The

Limited in its scope and widely ignored, the Mining Safety Law of 1870 had little impact, and mining hazards continued to be a widespread problem. "Robbing the pillars" was another example of dangerous practices encouraged by management. As miners excavated a "room," they left pillars of coal standing to help support the roof overhead; when all of the coal had been removed from a room, managers ordered the workers to remove remaining pillars. When the roof started "pressing" (down), sometimes it would emit a crackling sound. Sometimes it just fell.

The diversity of coal miners' ethnicity, religions, and languages made it difficult for them to organize. Avondale, in fact, had been blamed on the Irish, who had been angry about consistently receiving the lowliest and most dangerous jobs at the colliery. In part, this suspicion of the Irish was due to the secretive

The blame for subsequent rock falls or dynamite explosions that fatally injured miners was laid upon the Irish, then the Italians, and then the Slovaks. A belief in Anglo-American superiority was widespread in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and this prejudice was used by mine owners to divide the workers in order to stall something else that management opposed: unions.

Two more horrific events near the turn of the twentieth century helped unify mine workers and inspire their leaders. The first was the

The next year, 1897, a contingent of sheriff's deputies fired upon an unarmed procession of striking mine workers who were marching between the patch towns of Harwood and Lattimer in Luzerne County. The deputies killed nineteen and wounded thirty-six people in what became known as the

By 1900, establishing a grievance procedure throughout the anthracite fields was a major strike issue and the efforts of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) to organize anthracite workers gained ground. The great labor advocate

The tension between mine owners and workers crested during the long

From March to October 1902, 150,000 workers stayed out of the mines and in many ways steered the union to insist on their demands to ensure a fairer workplace. With the leadership of UMWA president John Mitchell, future Secretary of Labor

In the end, the Commission granted some of the workers' demands, yet was reluctant to disrupt the "business of mining" by empowering workers. Moreover, one result miners sought in the Great Strike of 1902 was not gained: company executives did not have to recognize the UMWA as an official union.

Future conflicts were inevitable, as were additional mine disasters. In 1911, the horrible

Under the new contract operators drove the men hard, firing at whim and cutting corners on equipment and safety regulations in their extraction of anthracite. During the Great Depression, a rival organization, the United Anthracite Miners of Pennsylvania (UAMP), arose and tried to meet the needs of anthracite workers in a dying industry.

By the 1920s and 1930s, consumers of anthracite began shifting to oil, natural gas and electricity. Stubborn coal executives, still locked into their hostile battle with labor, held on to their profits by reducing labor costs, leasing operations to small non-union operators, and did not develop new markets or technologies for anthracite. As the Great Depression shook the country and the world, northeastern Pennsylvania had already fallen on hard times.

The decline of anthracite can be measured in tons: the Pennsylvania fields produced nearly 100 million tons in 1917 and only 69 million in 1930. By the late 1940s, only 80,000 worked in the mines. As the industry continued its long decline, some men got three days of work a week; many got none. The older, more skilled miners (usually with larger families to support) were fired first because they earned more.

Anthracite workers and the UAMP called for "work equalization," in which companies would spread out the work across their mines rather than operating only one colliery where the coal was easiest to reach. The companies and the UMWA opposed this and other reforms. "Unemployed councils," another grass-roots initiative with thousands of participants, provided food and aid to the needy and called for unemployment insurance legislation.

Pressure nationwide pushed the Roosevelt administration, in 1935, to include unemployment compensation and a pension system in the Social Security Act. Social activism and militancy grew; there were violent clashes between workers and owners, and the UAMP president was killed with a package bomb. While unemployed miners dug pits for

The symbolic end of the anthracite coal era came in 1959, when the