Overview: William Still and the Underground Railroad

William Still was working as a clerk for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, when a former slave calling himself Peter Freedman turned up in his Philadelphia office. The older fugitive had an incredible story to tell, but the clerk was too busy to pay much attention. It was August 1850, and most anti-slavery activists were focused on the great national debate over slavery that was taking place in Congress. One excitable ex-slave from Alabama hardly compared to the importance of stopping the spread of slavery or preventing the passage of a new fugitive slave law. But as William Still fidgeted impatiently behind his desk, he suddenly realized that the man sitting across from him was actually his brother.

Still's parents were former slaves from Delaware who had been forced to leave behind two of their children when they managed to find freedom in New Jersey. The boys were eventually sold to a plantation owner in Alabama. One of them survived and was so bright and dependable that his owner hired him out to local shopkeepers. The talented slave then made friends with two Jewish merchants who agreed to buy him, and secretly let him work for his freedom. They even helped him come to the North. Now here he was -Peter Still- meeting his youngest brother for the first time.

William Still felt that he had discovered his life's calling. His work for the Anti-Slavery Society had brought him into contact with fugitives before. But like many northerners involved in the effort to help runaway slaves, known as the "Underground Railroad," he had never taken notes or kept records of those activities. It was considered too dangerous. After this unexpected reunion, however, he vowed not to let the fear of punishment prevent him from collecting evidence that might help some of slavery's other "bleeding and severed hearts" find each other.

During the 1850s, Still organized many of the Underground Railroad operations in Philadelphia. According to his records, the city's network of abolitionists helped more than 100 slaves escape each year. Most of the fugitives came from nearby slave regions like Delaware, Maryland, Virginia or Washington, D.C. They were often young men with special skills who had been hired out, providing them with more education and freedom of movement than typical plantation field hands.

The runaways crossed into Pennsylvania not only because it was close, but also because it contained the North's largest free African-American population, more than 56,000 residents by the eve of the Civil War. They also came to Pennsylvania because the state had a reputation for being antislavery. It had been the first state to adopt a gradual emancipation law. It had also been the first northern state to protect its black residents with personal liberty laws, written to prevent slavecatchers from kidnapping free blacks.

The story is complicated, however, because Pennsylvania was also an openly racist society. The state withdrew voting rights from African-American men in 1838. Some communities required free blacks to register their presence and limit their movements. Wherever blacks lived in Pennsylvania, there were occasional race riots or racially motivated assaults.

Despite these difficulties, the Underground Railroad operated in Pennsylvania from the 1830s until the coming of the Civil War. Nobody knows exactly how many slaves escaped to freedom, but southerners became increasingly enraged.

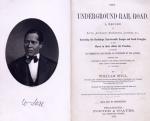

When the Civil War erupted, William Still gathered up his Underground Railroad records and hid them in a cemetery. He resigned from the Anti-Slavery Society and became a businessman who supplied materials to a nearby Union army camp that trained black soldiers. He grew wealthy, but did not forget his past. When the war was over and slavery was finally abolished, he published a book that described the workings of the Underground Railroad, the most complete first-hand account ever written.

Still's name was well known for a time, but eventually his celebrity faded. The importance of the Underground Railroad also was overshadowed in the years after the Civil War. Much of the physical history has since been lost. Many of the participants' memories went unrecorded. Only recently has this tragic indifference started to change. About 80 percent of the historical markers that support this story were dedicated after 1980. New efforts to preserve Underground Railroad heritage are being encouraged every year. It is possible that many more stories, as compelling as that of the Still family, remain to be discovered.

Still's parents were former slaves from Delaware who had been forced to leave behind two of their children when they managed to find freedom in New Jersey. The boys were eventually sold to a plantation owner in Alabama. One of them survived and was so bright and dependable that his owner hired him out to local shopkeepers. The talented slave then made friends with two Jewish merchants who agreed to buy him, and secretly let him work for his freedom. They even helped him come to the North. Now here he was -Peter Still- meeting his youngest brother for the first time.

William Still felt that he had discovered his life's calling. His work for the Anti-Slavery Society had brought him into contact with fugitives before. But like many northerners involved in the effort to help runaway slaves, known as the "Underground Railroad," he had never taken notes or kept records of those activities. It was considered too dangerous. After this unexpected reunion, however, he vowed not to let the fear of punishment prevent him from collecting evidence that might help some of slavery's other "bleeding and severed hearts" find each other.

During the 1850s, Still organized many of the Underground Railroad operations in Philadelphia. According to his records, the city's network of abolitionists helped more than 100 slaves escape each year. Most of the fugitives came from nearby slave regions like Delaware, Maryland, Virginia or Washington, D.C. They were often young men with special skills who had been hired out, providing them with more education and freedom of movement than typical plantation field hands.

The runaways crossed into Pennsylvania not only because it was close, but also because it contained the North's largest free African-American population, more than 56,000 residents by the eve of the Civil War. They also came to Pennsylvania because the state had a reputation for being antislavery. It had been the first state to adopt a gradual emancipation law. It had also been the first northern state to protect its black residents with personal liberty laws, written to prevent slavecatchers from kidnapping free blacks.

The story is complicated, however, because Pennsylvania was also an openly racist society. The state withdrew voting rights from African-American men in 1838. Some communities required free blacks to register their presence and limit their movements. Wherever blacks lived in Pennsylvania, there were occasional race riots or racially motivated assaults.

Despite these difficulties, the Underground Railroad operated in Pennsylvania from the 1830s until the coming of the Civil War. Nobody knows exactly how many slaves escaped to freedom, but southerners became increasingly enraged.

When the Civil War erupted, William Still gathered up his Underground Railroad records and hid them in a cemetery. He resigned from the Anti-Slavery Society and became a businessman who supplied materials to a nearby Union army camp that trained black soldiers. He grew wealthy, but did not forget his past. When the war was over and slavery was finally abolished, he published a book that described the workings of the Underground Railroad, the most complete first-hand account ever written.

Still's name was well known for a time, but eventually his celebrity faded. The importance of the Underground Railroad also was overshadowed in the years after the Civil War. Much of the physical history has since been lost. Many of the participants' memories went unrecorded. Only recently has this tragic indifference started to change. About 80 percent of the historical markers that support this story were dedicated after 1980. New efforts to preserve Underground Railroad heritage are being encouraged every year. It is possible that many more stories, as compelling as that of the Still family, remain to be discovered.