Pennsylvania Politics, 1865-1930.

If asked to name the most important Americans in history, most of us would certainly mention Washington, Franklin, and Jefferson from the revolutionary era, Lincoln, Grant, and Lee from the Civil War period, and both Roosevelts and Woodrow Wilson in the twentieth century. For the "Gilded Age," as Mark Twain called it, which stretched from the end of the Civil War until about 1900, however, politicians and generals would have to yield to Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and J.P. Morgan, whose public visibility and accomplishments far exceeded those of the contemporary presidents.

Their sayings, too, have become part of American folklore: "The public be damned" (Vanderbilt); "I can always hire half the working class to kill the other half" (Gould, when warned about the possibility of revolution); "He who dies rich, dies disgraced" (Carnegie); "God gave me my money" (Rockefeller); and "If you have to ask what it costs, you can't afford it" (J.P. Morgan, with respect to a yacht).

Pennsylvania played a key role in all their careers. Gould's first business venture was a tannery in Lackawanna County. Carnegie Steel, based in Pittsburgh, was America's largest steel producer. From it, financier J.P. Morgan would form U.S. Steel, the world's first billion-dollar corporation. Standard Oil was incorporated in Pennsylvania and extracted most of its oil from the state. Cornelius Vanderbilt's New York Central Railroad, like the Pennsylvania Railroad, made a deal with Rockefeller to ship his oil at lower prices than his competitors.

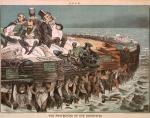

We disagree whether to call them "industrial statesmen" or "robber barons," but both terms convey their domination of the age. They had more wealth than the state and federal governments, and wielded more power. They acquired it not only through hard work and intelligence but through ruthless suppression of their enemies, unethical and, at times, downright criminal behavior. And they presided over a nation that increasingly approximated an aristocracy of wealth rather than a democratic republic.

How wealthy were they? At a time when laborers were earning $35 and Philadelphia schoolteachers made $47 a month, Carnegie and Rockefeller were making a million. By 1900, when the United States government spent less than half a billion dollars a year, corporations on which J.P. Morgan and his partners sat on the boards of directors held assets of $22 billion, a quarter of the gross national product. Business interests ruled the nation, and the vocabulary of industry came to describe American politics: a "boss" - although his real bosses were the businessmen - ran a "machine" to turn out a product: votes.

Feudal language also entered the American political vocabulary. To maintain their claims to dignity, America's first nationwide labor union called itself "the Knights of Labor." Farmers set up the "Grange," originally meaning a country estate, and became "the patrons of husbandry." Even those whom society preferred to call tramps, bums, and hoboes insisted they were "knights of the road." Feudal architecture also filled the nation's landscape. The first home in the United States to cost a million dollars - and the first private residence in the nation larger than the White House - was Ogontz, built in 1869 just north of Philadelphia by banker Jay Cooke, whose sale of war bonds helped the Union to fight the Civil War without the ruinous inflation suffered by the Confederacy.

Others followed: the Vanderbilt mansions at Biltmore, North Carolina; Newport, Rhode Island; and Hyde Park, New York; the palaces of Henry Clay Frick, Carnegie's second-in-command, in Pittsburgh and New York; the mansions of Lehigh Railroad President Asa Packer and his son in Mauch Chunk - all are now museums. Following the great railroad strike of 1877, frightened citizens built armories resembling medieval fortresses from which they could defend themselves. The rich sent their children to universities that resembled Oxford and Cambridge. Some even married into the European nobility: New York's Jennie Jerome and her husband, the Duke of Marlborough, had a son named Winston Churchill.

Pennsylvania was at the heart of this transformation of the America. It was an industrial powerhouse, leading the nation in the production of oil, coal, iron, steel, and lumber. The three largest corporations in the world by 1901, the Pennsylvania Railroad, Standard Oil, and U.S. Steel, did most of their business in the Keystone State.

Although economists speak of private enterprise or "laissez-faire" capitalism, they also acknowledge that every economic system requires a legal system to function effectively. Railroads received massive subsidies from the federal and often state governments. Coal mines required a plentiful, cheap, and subservient labor force. The tremendous urban growth of this period required the construction of schools, government buildings, streets, and trolleys, and other public works, that made municipal contractors rich and politically powerful.

The influx of millions of immigrants to the United States ensured there would always be plenty of low-cost labor available - and new voters to be wooed and manipulated. Workers injured on the job could not collect compensation without proving negligence on the company's part, almost impossible given their inability to pay for legal talent. Government at all levels - local, state, federal, legislative, executive, and judicial - usually considered strikes and union organizing violations of the natural laws of the free marketplace, and dangerous threats to the public peace if not downright revolutionary. And few laws protected the environment as forests disappeared, rivers and streams became dumping grounds for industrial wastes, and clouds of soot hovered over filthy cities with polluted water sources.

One law nearly all Pennsylvanians, whether bosses, workers, or reformers, believed vital to the state's prosperity was the tariff, to protect their industries from foreign competition. By the late 1800s, Pennsylvania needed no such protection, for it dominated the world markets in steel, oil, coal, and iron, but to generations of Pennsylvania congressmen and senators, the tariff was as sacred as the Bible and the flag.

Pennsylvania's economic might gave its Republican leaders' tremendous political power in Washington. The state produced no presidents after James Buchanan stepped down in 1861, but Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and Warren Harding in 1920 received the Republican nominations in large part through the influence of Pennsylvania bosses Simon Cameron and Boies Penrose, respectively.

Pennsylvania Railroad President Tom Scott was a key player in the deal by which the Democratic Party in 1876 acquiesced in the disputed election of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. Pennsylvania boss Matthew Quay ran Benjamin Harrison's successful national campaign for the presidency in 1888. James A. Beaver in 1880 and William Sproul in 1920 both turned down offers of the vice-presidency. Both would have been become president after Garfield's assassination in 1881 and Harding's untimely death in 1923. Pennsylvania Democrat and war hero General Winfield Scott Hancock narrowly lost the Presidency to Republican James Garfield in 1880.

The four chapters in this story explore Pennsylvania's politics and government between the end of the Civil War and onset of the Great Depression, and how in an era of bosses and political corruption, despite notable critics and reformers in the state, Pennsylvania led the nation in not only in industry, but in notoriety as well.

Their sayings, too, have become part of American folklore: "The public be damned" (Vanderbilt); "I can always hire half the working class to kill the other half" (Gould, when warned about the possibility of revolution); "He who dies rich, dies disgraced" (Carnegie); "God gave me my money" (Rockefeller); and "If you have to ask what it costs, you can't afford it" (J.P. Morgan, with respect to a yacht).

Pennsylvania played a key role in all their careers. Gould's first business venture was a tannery in Lackawanna County. Carnegie Steel, based in Pittsburgh, was America's largest steel producer. From it, financier J.P. Morgan would form U.S. Steel, the world's first billion-dollar corporation. Standard Oil was incorporated in Pennsylvania and extracted most of its oil from the state. Cornelius Vanderbilt's New York Central Railroad, like the Pennsylvania Railroad, made a deal with Rockefeller to ship his oil at lower prices than his competitors.

We disagree whether to call them "industrial statesmen" or "robber barons," but both terms convey their domination of the age. They had more wealth than the state and federal governments, and wielded more power. They acquired it not only through hard work and intelligence but through ruthless suppression of their enemies, unethical and, at times, downright criminal behavior. And they presided over a nation that increasingly approximated an aristocracy of wealth rather than a democratic republic.

How wealthy were they? At a time when laborers were earning $35 and Philadelphia schoolteachers made $47 a month, Carnegie and Rockefeller were making a million. By 1900, when the United States government spent less than half a billion dollars a year, corporations on which J.P. Morgan and his partners sat on the boards of directors held assets of $22 billion, a quarter of the gross national product. Business interests ruled the nation, and the vocabulary of industry came to describe American politics: a "boss" - although his real bosses were the businessmen - ran a "machine" to turn out a product: votes.

Feudal language also entered the American political vocabulary. To maintain their claims to dignity, America's first nationwide labor union called itself "the Knights of Labor." Farmers set up the "Grange," originally meaning a country estate, and became "the patrons of husbandry." Even those whom society preferred to call tramps, bums, and hoboes insisted they were "knights of the road." Feudal architecture also filled the nation's landscape. The first home in the United States to cost a million dollars - and the first private residence in the nation larger than the White House - was Ogontz, built in 1869 just north of Philadelphia by banker Jay Cooke, whose sale of war bonds helped the Union to fight the Civil War without the ruinous inflation suffered by the Confederacy.

Others followed: the Vanderbilt mansions at Biltmore, North Carolina; Newport, Rhode Island; and Hyde Park, New York; the palaces of Henry Clay Frick, Carnegie's second-in-command, in Pittsburgh and New York; the mansions of Lehigh Railroad President Asa Packer and his son in Mauch Chunk - all are now museums. Following the great railroad strike of 1877, frightened citizens built armories resembling medieval fortresses from which they could defend themselves. The rich sent their children to universities that resembled Oxford and Cambridge. Some even married into the European nobility: New York's Jennie Jerome and her husband, the Duke of Marlborough, had a son named Winston Churchill.

Pennsylvania was at the heart of this transformation of the America. It was an industrial powerhouse, leading the nation in the production of oil, coal, iron, steel, and lumber. The three largest corporations in the world by 1901, the Pennsylvania Railroad, Standard Oil, and U.S. Steel, did most of their business in the Keystone State.

Although economists speak of private enterprise or "laissez-faire" capitalism, they also acknowledge that every economic system requires a legal system to function effectively. Railroads received massive subsidies from the federal and often state governments. Coal mines required a plentiful, cheap, and subservient labor force. The tremendous urban growth of this period required the construction of schools, government buildings, streets, and trolleys, and other public works, that made municipal contractors rich and politically powerful.

The influx of millions of immigrants to the United States ensured there would always be plenty of low-cost labor available - and new voters to be wooed and manipulated. Workers injured on the job could not collect compensation without proving negligence on the company's part, almost impossible given their inability to pay for legal talent. Government at all levels - local, state, federal, legislative, executive, and judicial - usually considered strikes and union organizing violations of the natural laws of the free marketplace, and dangerous threats to the public peace if not downright revolutionary. And few laws protected the environment as forests disappeared, rivers and streams became dumping grounds for industrial wastes, and clouds of soot hovered over filthy cities with polluted water sources.

One law nearly all Pennsylvanians, whether bosses, workers, or reformers, believed vital to the state's prosperity was the tariff, to protect their industries from foreign competition. By the late 1800s, Pennsylvania needed no such protection, for it dominated the world markets in steel, oil, coal, and iron, but to generations of Pennsylvania congressmen and senators, the tariff was as sacred as the Bible and the flag.

Pennsylvania's economic might gave its Republican leaders' tremendous political power in Washington. The state produced no presidents after James Buchanan stepped down in 1861, but Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and Warren Harding in 1920 received the Republican nominations in large part through the influence of Pennsylvania bosses Simon Cameron and Boies Penrose, respectively.

Pennsylvania Railroad President Tom Scott was a key player in the deal by which the Democratic Party in 1876 acquiesced in the disputed election of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. Pennsylvania boss Matthew Quay ran Benjamin Harrison's successful national campaign for the presidency in 1888. James A. Beaver in 1880 and William Sproul in 1920 both turned down offers of the vice-presidency. Both would have been become president after Garfield's assassination in 1881 and Harding's untimely death in 1923. Pennsylvania Democrat and war hero General Winfield Scott Hancock narrowly lost the Presidency to Republican James Garfield in 1880.

The four chapters in this story explore Pennsylvania's politics and government between the end of the Civil War and onset of the Great Depression, and how in an era of bosses and political corruption, despite notable critics and reformers in the state, Pennsylvania led the nation in not only in industry, but in notoriety as well.