Overview: King Coal: Mining Bituminous

"Coal is to the world of industry what sun is to the natural world."

Coal was critical to the United States' industrial revolution. By the late nineteenth century it replaced wood as the preferred fuel for powering factories, locomotives, and ships, and displaced wood for home heating in the northeastern United States. In 1874 a coal miner stressed how central coal and miners' work had become, "I hope to see the miners of America realize that… they are foremost in producing wealth, that … millions of firesides of rich and poor must be supplied by our labor, that the magnificent steamer that ploughs the ocean, rivers and lakes, the locomotive, whose shrill whistle echoes and re-echoes from Maine to California, the rolling mills, the cotton mills, the flour mills, the world's entire machinery, is moved, propelled by our labor."

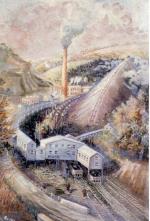

Mine owners and miners made Pennsylvania the nation's leading coal producer. Virtually all of the country's anthracite coal came from Pennsylvania, and anthracite production dominated the Commonwealth's coal output for most of the nineteenth century. In 1897 western Pennsylvania's bituminous mines surpassed anthracite production. The Keystone state led the nation in mining bituminous coal until the 1930s.

Coal is a rock that burns. It is found in two principal types: bituminous and anthracite. Bituminous coal, which is also called soft coal, has a significantly lower proportion of combustible carbon than anthracite coal, which is harder and is often called hard coal. Bituminous coal also is made into coke by burning the coal under controlled conditions to expel impurities which impede combustion, leaving a higher proportion of combustible carbon. Pennsylvania's bituminous coal fields lie at the northern end of the Appalachian coal fields, which extend from the Commonwealth to Alabama. Bituminous coal underlies more than 14,000 square miles and parts of thirty-three counties in western Pennsylvania.

Bituminous mining began on a small scale in southwestern Pennsylvania during the mid-eighteenth century. During the mid- and late nineteenth century the industry grew enormously, greatly increasing output and the numbers of mines and workers. Thousands of people settled in western Pennsylvania to labor at mines and coke works, greatly increasing the local population. At first American-born and British immigrant miners dominated the labor force, but during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, thousands of eastern and southern European immigrants provided cheap, mostly unskilled labor for the burgeoning industry.

Since operators usually opened mines in rural areas, they built dozens of towns or "coal patches" to house workers and their families. A coal patch reflected the occupational hierarchy and ethnic composition of the work force. A coal company constructed the best houses for mine supervisors and erected cheaper housing for workers. Different ethnic groups often settled in their own neighborhoods in larger coal patches. Coal miners' wages financed local businesses, including company stores that were centerpieces of many company towns.

Operators tightly controlled most mines and patch towns during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. They had power over families' personal lives to a degree not found in most other Pennsylvania communities. They typically controlled employment, housing, local government officials, and most businesses in coal patches, as well as private police that patrolled towns. Operators also reduced wages to meet growing competition for shrinking markets, particularly during the 1920s. Most employers saw workers as a production cost to be cut as well as controlled. When miners went on strike or tried to organize unions, operators fought back hard by firing workers, bringing in strikebreakers to replace them, using private police to protect mine property and strikebreakers, and evicting miners and their families from company housing.

Men and boys worked in the mines primarily to support themselves and their families. Alex Whoolery recounted, "I was forced to go [into the mines] because my dad was failing in health, and we had a large family of ten." Jerry Schuessler's father went to work at Moorewood Mine in the 1890s and later in Bittner. Schuessler explained why he followed his father into the mines. "My dad worked in a coal mine, and if you lived in a patch, you naturally went into the coal mine. Kids in those days [around 1920]–if the father worked in the mine–they went into the coal mine. Never any question about it!"

Work in the mines was hard and dangerous. Between 1877 and 1940, 18,000 men and boys died in Pennsylvania bituminous mines. Workers blamed operators for bad working conditions and low wages. Workers and employers viewed each other with hostility and distrust by the late nineteenth century. A miners' song published in 1913 expressed how many miners saw operators:

"Pick! Pick! Pick!

In the tunnel's endless gloom,

And every blow of our strong right arm

But helps to carve our tomb.

But what is that to thee

Who live by our blood and toil?

For mining royalties must be made

To glut the coal barons' spoils."

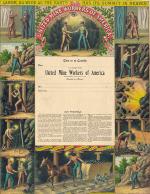

Miners went on strike and organized to gain better pay and working conditions and more power in the work place and patch town. Miners from Pennsylvania and other states formed the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) in 1890. This union staged a nationwide strike in 1897 and won recognition as the collective bargaining agent for miners at many bituminous mines in western Pennsylvania and other northern states. Between then and 1924, the UMWA organized anthracite workers in eastern Pennsylvania and gained pay raises and a shorter hours for miners.

The UMWA became the largest and most powerful union in the United States. However, during the mid-1920s, many Pennsylvania operators abrogated their contract with the UMWA and cut wages in order to meet competition especially from nonunion mines with lower wage rates in southern states. The UMWA rebounded greatly after 1933 with passage of federal legislation that supported unionization.

Beginning in the 1920s the Pennsylvania bituminous industry slipped into drastic decline. The industry faced a crisis of overproduction for shrinking markets. Operators closed mines and mechanized work, throwing thousands of miners out of work. Pennsylvania fell in national prominence as other states surpassed the Commonwealth's production. During the 1930s, West Virginia passed Pennsylvania, with Illinois, Kentucky, and Ohio lagging well behind. By 1972, West Virginia and Kentucky produced more coal than Pennsylvania, and Illinois was close behind. During the 1970s, Wyoming also became a major producer of coal.

The evolution of Pennsylvania's anthracite industry shows both similarities and differences to that of the bituminous industry. Anthracite mining began in the early 1800s, later than bituminous mining, but like bituminous extraction, anthracite mining grew enormously from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century. Beginning in the 1920s, it, too, suffered a drastic decline due to shrinking markets. Both industries had a long history of labor-management distrust and hostility, and the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) was also critical to organizing and representing workers in the anthracite region. But operators in the anthracite fields had less control over their workers. In the early 1900s less than one-third of anthracite miners lived in company-owned towns, as compared to about three-quarters of miners in bituminous fields.

Pennsylvania's bituminous and anthracite coal industries are greatly diminished from their peak during the early twentieth century. Many coal towns have lost population and businesses since mines closed, and some coal towns have disappeared entirely. Many operators have gone out of business and left a legacy of environmental damage. Even decades after the mines closed, some retirees and their families still view bituminous mining companies with hostility or fear.

Surviving miners and their families, however, also continue to speak with pride about their accomplishments. Susan Raytek, whose husband had labored in bituminous mines for forty-five years, spoke for many family survivors when she said, "I thank God every day for all our men who worked and fought for a better way of life, and for all the hardships, tragedies and strikes that we survived. Also, I am thankful to them for what income and benefits I now enjoy as a widow." The work of thousands in Pennsylvania's bituminous industry benefited the nation, and helped make bituminous coal the king of western Pennsylvania.