Overview: Pennsylvania and the New Nation

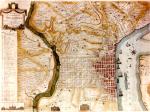

From 1783 to 1789 and from 1790-1800, Philadelphia was the capital of the nation, and the great issues that faced the country centered in the Keystone State. A circle of Pennsylvanians who were leaders in the national movement to replace the loosely affiliated states in the Articles of Confederation with a stronger government, were simultaneously working to replace Pennsylvania's Constitution of 1776. Two problems both existing governments had failed to solve were promotion of the general welfare - especially economic prosperity - and opening the west to settlement.

By the early 1780s, both the Pennsylvania and the national government had broken down. Neither had any money, and because neither the state nor nation could pay them, the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army mutinied twice, chasing Congress out of Philadelphia to Princeton, New Jersey. Many more conservative Pennsylvanians believed the 1776 state constitution had established a tyranny of the majority - under it a single legislative body ruled unchecked by a weak executive council - that denied the right to vote to pacifists, neutrals, and former Loyalists whose religion and principles prevented them from taking the required loyalty oath.

Impotence, perhaps, best described the national government. The states refused to support Congress, which had no money to pay its debts or remove Native Americans or the British troops stationed at Forts Detroit, Niagara, and other posts from its own territory.

While the Pennsylvania and national governments were broke in the early 1780s, the same was not true of Pennsylvanians themselves. Except for the frontier and the Philadelphia area during the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777-1778, the war had spared most of the state. Privateers supplied currency and imported goods; grain farmers and manufacturers profited from supplying the army. After the war, trade with the West Indies and Europe soared. The first American voyage to China, outfitted by Pennsylvania financier Robert Morris and his associates, netted more than £300,000.

Wealthy Pennsylvania merchants had the money to help the state and national governments, but insisted that their constitutions be revised to place both under their own leadership. The American banking industry arose in Philadelphia to render both governments solvent. On July 1, 1780, ninety-two Philadelphia merchants put up £315,000 of their own money to establish the Bank of the United States. The Bank of North America, chartered by Congress in December 1781, soon supplanted it.

Robert Morris, superintendent of finance for the national government, was the mover behind both banks, but Jewish financier Haym Salomon negotiated the loans from Holland that provided some solid backing for a severely inflated currency, which had risen about 1000 percent since the beginning of the war. Thomas Willing, Morris's patron and business partner, became the bank's president and then president of the First Bank of the United States, founded in 1791 as part of Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton's program to once again stabilize the nation's finances.

American independence also had an impact on women, who were now expected to educate their children to be virtuous and patriotic republican citizens. For the first time, women began to attend academies, such as the Philadelphia Female Academy, founded in 1787, and the Franklin Academy in Lancaster, where they were educated alongside of men.

Women also contributed to Pennsylvania's rich cultural life. Susanna Rowson, author of one of America's first novels, Charlotte Temple, performed at Philadelphia's Chestnut Street Theater from 1794 to 1796 and wrote several plays, including "The Slaves of Algiers," which dealt with the predicament of Americans taken prisoner by the Barbary pirates. Philadelphian Charles Brockden Brown became the first American to earn his living as a novelist. His novel Arthur Mervyn (1798) describes a country lad who thanks to a strong-minded Jewish woman survives scoundrels, economic hardship, and yellow fever epidemics.

Philadelphia was the nation's financial and cultural center and well as its capital. The city boasted the nation's first medical school, first museum (1786), first stock exchange (1791), insurance company (1792), paved road and turnpike (1792), the largest public building (the State House), and largest market. Philadelphia also led the nation in schemes and inventions to increase the nation's wealth. Here, merchant Tench Coxe in 1787 founded the Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures, and John Fitch in 1787 invented the first steam boat.

Both defense and economic development cost money, and not all Pennsylvanians were happy with the way the national government ordered them to provide it; with increased excise and property taxes. The first two citizen "rebellions" under the new federal government established by the United States Constitution both occurred in Pennsylvania: the so-called "Whiskey Rebellion" of farmers in the west in 1794, and "Fries Rebellion" of 1799, when eastern Pennsylvanians in Berks and Northampton counties rose up against taxes they considered unjust.

Pennsylvania was torn by internal divisions in the quarter century from 1775 to 1800. Many farmers and workers - one of the first strikes in the new nation was organized by the printers of Philadelphia in 1786 - disliked the fact that taxes and their efficient collection increased in the 1790s, and that the new state Senate, instituted with the Constitution of 1790s, made substantial wealth a requirement for election.

The institution of Senates at both levels–chosen by people with substantial property at the state level, and by the state legislatures at the national–and a powerful governor and president, assured that state assemblies could no longer postpone the collection of taxes largely used to pay debts that the governments owed to the wealthy both at home and in foreign countries. Both governments, however, also enabled the farmers and soldiers to head west by paying them with land for their service during the American Revolution. This plan, however, was only partially successful, as many veterans sold their "donation lands" at a fraction of their value to wealthy land speculators.

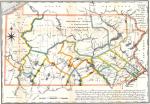

Pennsylvania's population soared from about 300,000 in 1770 to 434,000 in 1790 to 602,000 in 1800. The jump in the number of counties from eleven in 1773 to forty-two in 1804 reflects the rapid settlement of both the north and the west. In the decades following independence, the Commonwealth, like the nation, was able to confront its problems and emerge by 1800 poised to realize the hope Governor Thomas Mifflin expressed in his inaugural address in 1789: "Imagination can hardly paint the magnitude of the scene which demands our industry, nor hope exaggerate the richness of the reward which solicits our enjoyment." How those "improvements" would proceed and who would enjoy the "richness of the reward" have been the central questions of Pennsylvania history ever since.

By the early 1780s, both the Pennsylvania and the national government had broken down. Neither had any money, and because neither the state nor nation could pay them, the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army mutinied twice, chasing Congress out of Philadelphia to Princeton, New Jersey. Many more conservative Pennsylvanians believed the 1776 state constitution had established a tyranny of the majority - under it a single legislative body ruled unchecked by a weak executive council - that denied the right to vote to pacifists, neutrals, and former Loyalists whose religion and principles prevented them from taking the required loyalty oath.

Impotence, perhaps, best described the national government. The states refused to support Congress, which had no money to pay its debts or remove Native Americans or the British troops stationed at Forts Detroit, Niagara, and other posts from its own territory.

While the Pennsylvania and national governments were broke in the early 1780s, the same was not true of Pennsylvanians themselves. Except for the frontier and the Philadelphia area during the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777-1778, the war had spared most of the state. Privateers supplied currency and imported goods; grain farmers and manufacturers profited from supplying the army. After the war, trade with the West Indies and Europe soared. The first American voyage to China, outfitted by Pennsylvania financier Robert Morris and his associates, netted more than £300,000.

Wealthy Pennsylvania merchants had the money to help the state and national governments, but insisted that their constitutions be revised to place both under their own leadership. The American banking industry arose in Philadelphia to render both governments solvent. On July 1, 1780, ninety-two Philadelphia merchants put up £315,000 of their own money to establish the Bank of the United States. The Bank of North America, chartered by Congress in December 1781, soon supplanted it.

Robert Morris, superintendent of finance for the national government, was the mover behind both banks, but Jewish financier Haym Salomon negotiated the loans from Holland that provided some solid backing for a severely inflated currency, which had risen about 1000 percent since the beginning of the war. Thomas Willing, Morris's patron and business partner, became the bank's president and then president of the First Bank of the United States, founded in 1791 as part of Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton's program to once again stabilize the nation's finances.

American independence also had an impact on women, who were now expected to educate their children to be virtuous and patriotic republican citizens. For the first time, women began to attend academies, such as the Philadelphia Female Academy, founded in 1787, and the Franklin Academy in Lancaster, where they were educated alongside of men.

Women also contributed to Pennsylvania's rich cultural life. Susanna Rowson, author of one of America's first novels, Charlotte Temple, performed at Philadelphia's Chestnut Street Theater from 1794 to 1796 and wrote several plays, including "The Slaves of Algiers," which dealt with the predicament of Americans taken prisoner by the Barbary pirates. Philadelphian Charles Brockden Brown became the first American to earn his living as a novelist. His novel Arthur Mervyn (1798) describes a country lad who thanks to a strong-minded Jewish woman survives scoundrels, economic hardship, and yellow fever epidemics.

Philadelphia was the nation's financial and cultural center and well as its capital. The city boasted the nation's first medical school, first museum (1786), first stock exchange (1791), insurance company (1792), paved road and turnpike (1792), the largest public building (the State House), and largest market. Philadelphia also led the nation in schemes and inventions to increase the nation's wealth. Here, merchant Tench Coxe in 1787 founded the Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures, and John Fitch in 1787 invented the first steam boat.

Both defense and economic development cost money, and not all Pennsylvanians were happy with the way the national government ordered them to provide it; with increased excise and property taxes. The first two citizen "rebellions" under the new federal government established by the United States Constitution both occurred in Pennsylvania: the so-called "Whiskey Rebellion" of farmers in the west in 1794, and "Fries Rebellion" of 1799, when eastern Pennsylvanians in Berks and Northampton counties rose up against taxes they considered unjust.

Pennsylvania was torn by internal divisions in the quarter century from 1775 to 1800. Many farmers and workers - one of the first strikes in the new nation was organized by the printers of Philadelphia in 1786 - disliked the fact that taxes and their efficient collection increased in the 1790s, and that the new state Senate, instituted with the Constitution of 1790s, made substantial wealth a requirement for election.

The institution of Senates at both levels–chosen by people with substantial property at the state level, and by the state legislatures at the national–and a powerful governor and president, assured that state assemblies could no longer postpone the collection of taxes largely used to pay debts that the governments owed to the wealthy both at home and in foreign countries. Both governments, however, also enabled the farmers and soldiers to head west by paying them with land for their service during the American Revolution. This plan, however, was only partially successful, as many veterans sold their "donation lands" at a fraction of their value to wealthy land speculators.

Pennsylvania's population soared from about 300,000 in 1770 to 434,000 in 1790 to 602,000 in 1800. The jump in the number of counties from eleven in 1773 to forty-two in 1804 reflects the rapid settlement of both the north and the west. In the decades following independence, the Commonwealth, like the nation, was able to confront its problems and emerge by 1800 poised to realize the hope Governor Thomas Mifflin expressed in his inaugural address in 1789: "Imagination can hardly paint the magnitude of the scene which demands our industry, nor hope exaggerate the richness of the reward which solicits our enjoyment." How those "improvements" would proceed and who would enjoy the "richness of the reward" have been the central questions of Pennsylvania history ever since.