Chapter 3: War and Crisis in Indian Pennsylvania, 1754-1784

Why did the American patriots put an $800 price on

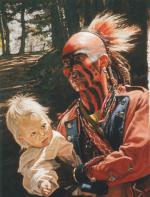

While still a teenager, Simon Girty was taken captive by Indians during the French and Indian War. He lived among the Seneca in the Ohio Country for several years, learning Indian languages and customs, but eventually returning to white society at the end of the war. Girty then made a name for himself among the Indians, colonists, and soldiers who lived in the vicinity of Fort Pitt, working as an interpreter, fur trader, and scout who bridged the gap between native and colonial worlds.

During the American Revolution his reputation among white Americans changed. Patriots in western Pennsylvania accused him of planning an Indian assault on Pittsburgh, and he decided to join the British cause, participating in Indian and loyalist raids against Pennsylvania's settlers and soldiers. The American patriots even offered an $800 reward for his arrest or proof of his death. By the time the war ended, Girty was one of the most hated men in the newly independent United States. He left the Ohio Country, a region he had inhabited since his childhood, and spent the rest of his days in British Canada, an inveterate enemy of people who had once claimed him as kin.

Had Girty lived a generation earlier, his story might have been very different. The skills he acquired by living among the Indians might have made him a wealthy trader and influential mediator in Pennsylvania's Indian relations. Several such figures, such as

The French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years' War, began as a contest over control of the Allegheny-Ohio watershed, a region contemporaries referred to as the Ohio Country. To the British and French, this was a contest between imperial powers for control of the North American interior, but for the Indians who lived there, it was a battle to defend their homelands from an ever-increasing tide of European encroachment. When a small force of soldiers led by George Washington tried to force the French to abandon their fortifications in the Ohio Country in 1754, the Delaware, Shawnee, and Iroquois Indians who lived there were anxious to have the help of the British but were skeptical of their motives.

A year later, the Indians' suspicions were confirmed when the British marched a much larger army to the Forks of the Ohio to confront the French. Asked by the Indians to acknowledge their right to the Ohio Country, General Edward Braddock declared abruptly that "No Savage Should Inherit the Land" he intended to occupy.

In the wake of Braddock's Defeat, the Pennsylvania frontier erupted in violence. Supplied at

The intercultural warfare that plagued Pennsylvania for the next forty years had no precedent in the colony's history. Each side committed atrocities against the other, murdering non-combatants, burning homes and crops, and mutilating corpses. At the raid on

Vigilante frontiersmen known as the Paxton Boys engaged in a similar bloody episode in December 1763, when they destroyed the

The escalation of intercultural violence continued unabated through the second half of the eighteenth century. On the European side, "Indian-hating" became an acceptable means of addressing the presence of Indians within Pennsylvania's borders. Although the Quakers and Moravians tried to restore peace, the majority of Pennsylvania's white inhabitants increasingly regarded all Indians as degenerate savages fit only for death or exile.

On the Indian side, spiritual movements arose during the French and Indian War (1754-60), Pontiac's Rebellion (1763-64), and the American Revolution (1775-83) that emphasized the need for all Indians to restore their cultural integrity and autonomy by disavowing European liquor, Christian missionaries, and any other accommodations to white society.

As each side drew further apart from the other, those Indians and Europeans who tried to bridge the gap between them found their work increasingly difficult. Moravian missionary

After the French and Indian War, the Delaware towns he had sought to defend through negotiation, such as

It is no wonder then that someone like Simon Girty found it impossible to remain a part of Indian and white worlds during the second half of the eighteenth century. Whatever personal failings or strengths Girty may have had (and contemporary accounts attributed many to him), they could not compensate for the fact that the world he lived in was changing abruptly.

The horrors of war made it impossible for Indians and whites to forgive the differences of the past or to mediate those of the present. Their fingers pried one by one from the great river systems that had been their homelands - the Delaware, the Susquehanna, the Allegheny-Ohio - Indians decided that their survival depended on distancing themselves both culturally and physically from white society. Whites, on the other hand, used these wars as convenient justifications for killing, exiling, or permanently disenfranchising Indians in the new American nation.