Chapter 1: The Theater

"Too oft, we own, the stage with dangerous art

In wanton scenes, has play'd a Syren's part,

Yet if the Muse, unfaithful to her trust,

Has sometimes stray'd from what was pure and just;

Has she not oft, with awful virtue's rage.

Struck home at vice, and nobly trod the stage?

Then as you'd treat a favourite fair's mistake,

Pray spare her foibles for her virtues stake:

And whilst her chastest scenes are made appear,

(For none but such will find admittance here)

The muse's friends, we hope, will join the cause,

And crown our best endeavours with applause."

Prologue to first performance of Hallam's Company in Philadelphia, 1754.

Applause was hard to come by in colonial Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania's Quaker founders were no friends of the theater, or of bearbaiting and bullbaiting, cock fighting, equestrian performances and horse racing, tight-rope dancing, or the other amusements, whose "very mischievous effects" as the Common Council had warned after the first recorded theatrical performance took place in Philadelphia in 1749, encouraged idleness and drew "great sums of money from weak and inconsiderate persons."

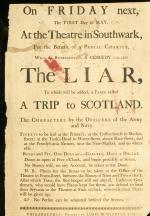

When Lewis Hallam's Company arrived from London in 1754, distressed local citizens forced them to move outside Philadelphia on the other side of South Street, where they constructed Pennsylvania's first theater. By 1760 Hallam's troupe had won sufficient local favor to open the larger Southwark Theater at 4th and South Streets - again outside the city's borders. The next year, the Privy Council in England struck down the Pennsylvania legislature's attempt to ban all theater in the colony. No friend of distractions or extravagances, the first Continental Congress in 1774 banned all theatrical performances "and other

While resident in Philadelphia as the new nation's first president, George Washington attended the Southwark Theater in a box specially fitted with cushioned seats, red drapes, and the United States" coat of arms. The president was also a great fan of riding. So when Englishman

Theater in the early republic offered a broad mix of entertainments. Houses interspersed their plays - Shakespeare was always a favorite - with acts by jugglers, dancers, singers, trained animals, one-act farces, and other diversions. For decades the American stage was dominated by imports from England, both plays and actors. By the 1820s, however, nationalistic Americans were seeking their theatrical independence, and they found their champion in the person of the stocky, full-throated, histrionic, and always exciting Philadelphian

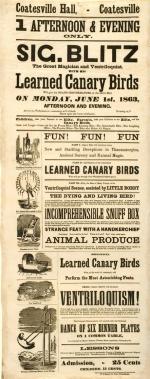

In the middle decades of the 1800s, Pennsylvania's economy was booming. The anthracite industry was taking off in the northeast, and western Pennsylvania was the world's leading producer of oil. Railroads were threading the state - and nation - together, carrying the raw materials and finished products of the Commonwealth's booming iron, textile, timber and other industries to market and mill. They were also carrying a growing collection of traveling stock companies, elocutionists, minstrel troupes, ventriloquists, humorists, and other entertainers to lodge halls, converted barns, and other makeshift theaters sprouting up across the state. Among them was "Professor"

As towns grew and prospered, local businessmen constructed handsome theaters, like Lancaster's

In the 1890s Isaac Mishler organized a circuit of theaters in twenty-four cities in eastern Pennsylvania that extended from Lancaster through Allentown up to Wilkes-Barre and Scranton. Based in Altoona along the main line of the Pennsylvania Railroad the

By the 1830s New York had surpassed Philadelphia as the center of American show business. But the Quaker City continued to support a thriving entertainment industry and to be a training ground for performers. Philadelphia boasted three resident stock companies, which toured the state when their season was over in the city. The family of Joseph Jefferson, America's most popular comic actor of the late 1800s, for three generations was associated with the Chestnut Street Theater. At the Arch Street, Mrs. John Drew ran one of the nation's most celebrated theaters and was matriarch of the

By 1900, vaudeville was all the rage, and a small handful of New York theatrical barons controlled a vast national network of theaters and the booking of acts. Altoona was loved on the national vaudeville circuit. Scranton was infamous for its tough audiences and Pittsburgh for its tough theater owners. The Majestic Theater in Gettysburg and Poli in Wilkes-Barre were part of the "medium time" vaudeville circuit for performers honing their acts in preparation for the "big time." Philadelphia was known both as "Sleepyville" and as "the cradle of vaudeville," for giving so many first-class performers their start. Stars

By the 1910s, Philadelphia's African-American community had become large and diverse enough to support two black-owned theaters, the

Close to Manhattan, Philadelphia in the 1920s became a tryout town for musicals and plays working out the kinks on their way to Broadway. Christened "The Genius Belt" in the 1930s for the concentration of famous literary figures, the Bucks County countryside in the 1940s

In the Poconos, the

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, theater continues to thrive in Pennsylvania. Towns and cities across the state are rehabilitating old theaters where amateur and professional troupes perform classic works and new productions. Resident ensemble companies along Philadelphia's thriving Avenue of the Arts perform new works. Comedians hone their acts at comedy clubs and in college auditoriums, and colleges and universities train new generations of actors and dancers, choreographers, and playwrights.