Chapter One: Building Pennsylvania's Railroads: The Story of Capital and Labor

In the 1800s, American railroads were powerful engines of economic growth, threading together previously isolated and distant regions into a fast-growing but at times chaotic national economy. Railroad development created hundreds of thousands of jobs and enabled a few men to accumulate fabulous fortunes. Blessed with rich farmland, and vast reserves of timber, coal, iron ore, and other natural resources, Pennsylvania quickly became a national leader in the construction of railroads that enabled it become an industrial powerhouse.

Pennsylvania's railroads also embodied the conflicting forces of America's free market system, and the intense, and at times violent battle between capital and labor. In the early 1800s, the typical American business was financed by individuals, families, or a few working in partnership. By contrast, the new railroading industry required massive capital investment, and created complex organizational and management structures. The explosive growth of the railroads and its related industries revolutionized industrial management and methods, and drastically changed the lives of working men and women.

From the start, politicians were intimately involved in the development of Pennsylvania's railroads. In the 1830s, state commissioners for Pennsylvania's Main Line of Public Works dispensed construction contracts to favored clients. Thaddeus Stevens, the famous abolitionist and Congressional leader of Radical Reconstruction after the Civil War, was an early railroad speculator. His infamous "Tapeworm Railroad," a name coined by his political enemies - was a fiasco that ate up $700,000 of state funding before work on it was abandoned.

"Tapeworm Railroad," a name coined by his political enemies - was a fiasco that ate up $700,000 of state funding before work on it was abandoned.

By the 1870s Pennsylvania Railroad president, Thomas A. Scott's political power was so great that on a day of unusually heavy legislative activity, one lawmaker - after the chamber had voted to approve several bills that the PRR wanted -was reported to have asked the presiding officer, "Mr. Speaker, may we now go Scott free?" Another tale was that one legislative session ended as follows: "The Pennsylvania Railroad having no more business to come before this chamber, we stand adjourned." For decades afterwards PRR's lobbyist was known as the state's unofficial "51st senator." (Now as then, Pennsylvania's State Senate still consists of fifty members.)

Two other industrial tycoons with holdings in Pennsylvania railroading - Jay Gould and

Jay Gould and  Andrew Carnegie - became symbols of the captains of industry who cared little for employee needs or rights. For many, Gould epitomized the "robber barons" of the age, while Carnegie redeemed his reputation by giving away most of his fortune to worthy causes. Another wealthy railroad president of the period,

Andrew Carnegie - became symbols of the captains of industry who cared little for employee needs or rights. For many, Gould epitomized the "robber barons" of the age, while Carnegie redeemed his reputation by giving away most of his fortune to worthy causes. Another wealthy railroad president of the period,  Asa Packer, who built much of what became the Lehigh Valley Railroad, used his wealth to serve the public in elective office and to endow Lehigh University.

Asa Packer, who built much of what became the Lehigh Valley Railroad, used his wealth to serve the public in elective office and to endow Lehigh University.

In the late 1800s, Pennsylvania's railroads rapidly expanded as their owners gobbled up coal mining, iron, and other supporting industries, and worked to eliminate competition and accumulate greater capital. Locomotive engineers, shop men, and other skilled railway workers were relatively well paid. Many of the impoverished and unskilled European immigrants and African Americans who worked for Pennsylvania's railroads, however, received low wages for the most physically demanding and dangerous work. Some, like the fifty-seven Irish immigrants hired by the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad in 1832 to build a railroad track fill known as

Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad in 1832 to build a railroad track fill known as  Duffy's Cut, died in anonymity.

Duffy's Cut, died in anonymity.

Like other industries in the 1800s, railroads insisted on their right to control wages and work conditions without the interference of government–or their workers. Railroads were massive enterprises that required a great variety of skilled, unskilled, and white-collar labor to conduct their complex and, necessarily, highly organized business. The need to control and coordinate personnel, equipment, operations, and finance over a wide geographic range forced the trunk-line railroads to develop complex organizational and management structures. In the case of PRR, its top officers had served the Union in the Civil War as transportation advisors, and they brought back to the peacetime railroad world the principle of military chain-of-command hierarchy as a management model.

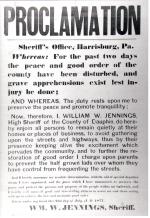

After the Civil War, economic cycles of boom and bust, often fed by the intense, at times cutthroat competition led to open conflict between the railroads and their workers. In 1873, when worldwide markets crashed and the nation entered a depression that lasted a record-breaking sixty-five months, millions lost their jobs. Railroads cut wages, and increased the work of those who still had jobs. When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) announced a 10 percent wage reduction in the summer of 1877, exasperated workers walked out first in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and then across the nation. Soon more than 100,000 men were participating in the first nationwide strike in American history, a strike that quickly turned ugly.

Some of the worst violence of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 took place in Pittsburgh, where outraged mobs burned and destroyed millions of dollars worth of locomotives, tracks, and equipment. Ten days of tension and violence left thirty-one people dead, and countless others wounded. In Reading, ten workers were shot dead and dozens wounded in what became known as the Reading Railroad Massacre.

Great Railroad Strike of 1877 took place in Pittsburgh, where outraged mobs burned and destroyed millions of dollars worth of locomotives, tracks, and equipment. Ten days of tension and violence left thirty-one people dead, and countless others wounded. In Reading, ten workers were shot dead and dozens wounded in what became known as the Reading Railroad Massacre.

By the time the 1877 strikes were over, more than 100 men, women, and children had been killed, 1,000 imprisoned, and movement on over half of the nation's rail lines had been temporarily halted. The national press rallied around the railroads, reviling the strikers and those who joined them as "hoodlums," "loafers," "malcontents," and even "enemies of society." But in the decades that followed, railroad workers joined with workers in other industries in great labor struggles.

During the Pullman strike of 1894 more than 260,000 American railroad workers walked off their jobs and shut down the nation's rail system as violent clashes broke out in twenty-six states. In 1909, the McKees Rock Steel Strike at the Pressed Steel Car Company in Allegheny County Pennsylvania helped make the International Workers of the World a powerful force for industrial unionism.

McKees Rock Steel Strike at the Pressed Steel Car Company in Allegheny County Pennsylvania helped make the International Workers of the World a powerful force for industrial unionism.

In the late 1800s, many railroads began to establish their own voluntary insurance, sick pay, pension, and death-benefit programs. The B&O set up such a program in 1887, and the Pennsylvania Railroad did so in 1900. Paying for the programs out of current operating revenues, the two lines felt no obligation to pay all benefits if they had a bad year financially. While these programs were imperfect, they did replace earlier unwritten practices, whereby managers rewarded employees or their survivors with discretionary bonuses, benefits, or funeral expenses based at times on nothing more tangible than ad hoc preferences and personal whims. More than 400 railroad and other industrial pension/benefit programs were set up after the B&O and PRR programs began, and they served as a safety net of sorts until the coming of the federal Railroad Retirement Act in 1937.

In the late 1800s mounting public pressure led to the passage of state and federal legislation to regulate an industry that had come to dominate the national economy. Farmers working through state chapters of the National Grange - won legislation to regulate the rates that railroads could charge to carry their products to market. Railroad worker safety took a major step forward in 1900 with the passage of federal legislation mandating that railroads install air brakes and automatic knuckle couplers. In 1908, passage of the Federal Employers" Liability Act ended the long-held legal principle that railroaders worked at their own risk, that they were usually responsible for their own misfortunes in accidents, and that acts of negligence by "fellow-servants" (co-workers) exonerated the company from liability.

the National Grange - won legislation to regulate the rates that railroads could charge to carry their products to market. Railroad worker safety took a major step forward in 1900 with the passage of federal legislation mandating that railroads install air brakes and automatic knuckle couplers. In 1908, passage of the Federal Employers" Liability Act ended the long-held legal principle that railroaders worked at their own risk, that they were usually responsible for their own misfortunes in accidents, and that acts of negligence by "fellow-servants" (co-workers) exonerated the company from liability.

Through it all the Pennsylvania Railroad and the state's other trunkline railroads prospered. In the first few decades of the twentieth century, PRR built its $112-million complex of tunnels, yards, and the palatial Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan, and spent many millions more on new freight yards and main line improvements, and massive new stations in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, and Chicago. PRR President Alexander J. Cassatt was the driving force behind the creation of a "community of interest" among major eastern railroads to bring order out of the rate-cutting chaos instigated by weaker trunk lines. In so doing, Cassatt organized a legal cartel in which strong trunk lines bought stock control of weak competitors in order to control the setting of rates and to moderate the cycles of economic growth and contraction.

Under Cassatt the PRR achieved the pinnacle of its power and influence in Washington, in the state capitols of the states it served, in Wall Street, and in the lives of its employees and the passengers, shippers, competitors, and suppliers with whom it did business. At its peak in the early 1900s, PRR employed close to 280,000 people, more than any other railroad in the nation.

But the Progressive movement of the early 1900s, reacting to the arrogance of Robber Baron days, brought regulation of the industry that ranged from the rates charged to ship firebrick from Mount Union to Pittsburgh, to schedules for locomotive-boiler inspections, to the size and placement of brakemen's handholds on the sides of freight cars. Antitrust legislation, coupled with federal rate regulation, ended the need for Cassatt's community of interest.

During World War I, the federal government took over operation of the nation's railroads to coordinate and facilitate movement of defense materiel. When it did so, it boosted railroad employment to more than two million nationwide, and gave formal recognition to railroad unions that had been unsuccessfully seeking a greater voice. When the war ended and the corporations resumed control of the railroads, they rescinded those agreements, rolling back many gains that workers had won. As the industry's largest employer, PRR was a bellwether for railroad labor relations throughout the nation.

The U.S. Railroad Labor Board attempted to coerce PRR into recognizing labor, but the railroad instead insisted that its "Employee Representation Plan" - a company union -was fair and was what PRR employees wanted. PRR defied and openly ignored the labor board, defeating it in a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. PRR won national attention in 1922 when 400,000 railroad shopmen went on strike nationally. The railroad kept running by quickly filling strikers" vacant jobs with other workers. In the quintessential railroad town of Altoona, where 16,000 men labored in the

Altoona, where 16,000 men labored in the  Pennsylvania Railroad Shops, only a handful walked out.

Pennsylvania Railroad Shops, only a handful walked out.

Railroad workers achieved significant gains in the 1930s and 1940s - despite drawing the ire of President Harry S. Truman, who seized the nation's railroads during a 1946 strike by engineers and trainmen, and threatened to send the Army to operate trains until a last-minute settlement ended the standoff. But the unions lost influence in the 1950s, as profound technological changes depleted their ranks - and then led to collapse of the once mighty industry.

No markers tell the story of the decline of the railroads' enormous influence in American life, law, and culture. But it is a story well worth telling. As diesel locomotives replaced steam engines, the number of workers needed to build, man, and service engines plummeted. In the middle decades of the twentieth century the automobile and trucking industries drew passengers and freight away from American railroads. Shifts in public policy also undermined the financial health of the industry, as the federal government poured billions of dollars of public money into the construction of interstate highways and airports, and ended the haulage of mail by the rails, which led to the discontinuance of hundreds of passenger trains, and with them went the jobs of those who ran and serviced the trains. Starved for cash by the late 1950s, many railroads declared bankruptcy.

Nationwide and in Pennsylvania, the health of the industry did not return until, again, action came at the federal level. Faced with a choice of liquidation of the railroads, nationalization, or a restoration of private enterprise, Congress chose the latter, passing the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, which began to restore the economic health of the industry. At the dawn of the twenty-first century the American railroad industry employed only 220,000 workers, one-ninth of the number in 1920.

Pennsylvania's railroads also embodied the conflicting forces of America's free market system, and the intense, and at times violent battle between capital and labor. In the early 1800s, the typical American business was financed by individuals, families, or a few working in partnership. By contrast, the new railroading industry required massive capital investment, and created complex organizational and management structures. The explosive growth of the railroads and its related industries revolutionized industrial management and methods, and drastically changed the lives of working men and women.

From the start, politicians were intimately involved in the development of Pennsylvania's railroads. In the 1830s, state commissioners for Pennsylvania's Main Line of Public Works dispensed construction contracts to favored clients. Thaddeus Stevens, the famous abolitionist and Congressional leader of Radical Reconstruction after the Civil War, was an early railroad speculator. His infamous

By the 1870s Pennsylvania Railroad president, Thomas A. Scott's political power was so great that on a day of unusually heavy legislative activity, one lawmaker - after the chamber had voted to approve several bills that the PRR wanted -was reported to have asked the presiding officer, "Mr. Speaker, may we now go Scott free?" Another tale was that one legislative session ended as follows: "The Pennsylvania Railroad having no more business to come before this chamber, we stand adjourned." For decades afterwards PRR's lobbyist was known as the state's unofficial "51st senator." (Now as then, Pennsylvania's State Senate still consists of fifty members.)

Two other industrial tycoons with holdings in Pennsylvania railroading -

In the late 1800s, Pennsylvania's railroads rapidly expanded as their owners gobbled up coal mining, iron, and other supporting industries, and worked to eliminate competition and accumulate greater capital. Locomotive engineers, shop men, and other skilled railway workers were relatively well paid. Many of the impoverished and unskilled European immigrants and African Americans who worked for Pennsylvania's railroads, however, received low wages for the most physically demanding and dangerous work. Some, like the fifty-seven Irish immigrants hired by the

Like other industries in the 1800s, railroads insisted on their right to control wages and work conditions without the interference of government–or their workers. Railroads were massive enterprises that required a great variety of skilled, unskilled, and white-collar labor to conduct their complex and, necessarily, highly organized business. The need to control and coordinate personnel, equipment, operations, and finance over a wide geographic range forced the trunk-line railroads to develop complex organizational and management structures. In the case of PRR, its top officers had served the Union in the Civil War as transportation advisors, and they brought back to the peacetime railroad world the principle of military chain-of-command hierarchy as a management model.

After the Civil War, economic cycles of boom and bust, often fed by the intense, at times cutthroat competition led to open conflict between the railroads and their workers. In 1873, when worldwide markets crashed and the nation entered a depression that lasted a record-breaking sixty-five months, millions lost their jobs. Railroads cut wages, and increased the work of those who still had jobs. When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) announced a 10 percent wage reduction in the summer of 1877, exasperated workers walked out first in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and then across the nation. Soon more than 100,000 men were participating in the first nationwide strike in American history, a strike that quickly turned ugly.

Some of the worst violence of the

By the time the 1877 strikes were over, more than 100 men, women, and children had been killed, 1,000 imprisoned, and movement on over half of the nation's rail lines had been temporarily halted. The national press rallied around the railroads, reviling the strikers and those who joined them as "hoodlums," "loafers," "malcontents," and even "enemies of society." But in the decades that followed, railroad workers joined with workers in other industries in great labor struggles.

During the Pullman strike of 1894 more than 260,000 American railroad workers walked off their jobs and shut down the nation's rail system as violent clashes broke out in twenty-six states. In 1909, the

In the late 1800s, many railroads began to establish their own voluntary insurance, sick pay, pension, and death-benefit programs. The B&O set up such a program in 1887, and the Pennsylvania Railroad did so in 1900. Paying for the programs out of current operating revenues, the two lines felt no obligation to pay all benefits if they had a bad year financially. While these programs were imperfect, they did replace earlier unwritten practices, whereby managers rewarded employees or their survivors with discretionary bonuses, benefits, or funeral expenses based at times on nothing more tangible than ad hoc preferences and personal whims. More than 400 railroad and other industrial pension/benefit programs were set up after the B&O and PRR programs began, and they served as a safety net of sorts until the coming of the federal Railroad Retirement Act in 1937.

In the late 1800s mounting public pressure led to the passage of state and federal legislation to regulate an industry that had come to dominate the national economy. Farmers working through state chapters of

Through it all the Pennsylvania Railroad and the state's other trunkline railroads prospered. In the first few decades of the twentieth century, PRR built its $112-million complex of tunnels, yards, and the palatial Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan, and spent many millions more on new freight yards and main line improvements, and massive new stations in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, and Chicago. PRR President Alexander J. Cassatt was the driving force behind the creation of a "community of interest" among major eastern railroads to bring order out of the rate-cutting chaos instigated by weaker trunk lines. In so doing, Cassatt organized a legal cartel in which strong trunk lines bought stock control of weak competitors in order to control the setting of rates and to moderate the cycles of economic growth and contraction.

Under Cassatt the PRR achieved the pinnacle of its power and influence in Washington, in the state capitols of the states it served, in Wall Street, and in the lives of its employees and the passengers, shippers, competitors, and suppliers with whom it did business. At its peak in the early 1900s, PRR employed close to 280,000 people, more than any other railroad in the nation.

But the Progressive movement of the early 1900s, reacting to the arrogance of Robber Baron days, brought regulation of the industry that ranged from the rates charged to ship firebrick from Mount Union to Pittsburgh, to schedules for locomotive-boiler inspections, to the size and placement of brakemen's handholds on the sides of freight cars. Antitrust legislation, coupled with federal rate regulation, ended the need for Cassatt's community of interest.

During World War I, the federal government took over operation of the nation's railroads to coordinate and facilitate movement of defense materiel. When it did so, it boosted railroad employment to more than two million nationwide, and gave formal recognition to railroad unions that had been unsuccessfully seeking a greater voice. When the war ended and the corporations resumed control of the railroads, they rescinded those agreements, rolling back many gains that workers had won. As the industry's largest employer, PRR was a bellwether for railroad labor relations throughout the nation.

The U.S. Railroad Labor Board attempted to coerce PRR into recognizing labor, but the railroad instead insisted that its "Employee Representation Plan" - a company union -was fair and was what PRR employees wanted. PRR defied and openly ignored the labor board, defeating it in a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. PRR won national attention in 1922 when 400,000 railroad shopmen went on strike nationally. The railroad kept running by quickly filling strikers" vacant jobs with other workers. In the quintessential railroad town of

Railroad workers achieved significant gains in the 1930s and 1940s - despite drawing the ire of President Harry S. Truman, who seized the nation's railroads during a 1946 strike by engineers and trainmen, and threatened to send the Army to operate trains until a last-minute settlement ended the standoff. But the unions lost influence in the 1950s, as profound technological changes depleted their ranks - and then led to collapse of the once mighty industry.

No markers tell the story of the decline of the railroads' enormous influence in American life, law, and culture. But it is a story well worth telling. As diesel locomotives replaced steam engines, the number of workers needed to build, man, and service engines plummeted. In the middle decades of the twentieth century the automobile and trucking industries drew passengers and freight away from American railroads. Shifts in public policy also undermined the financial health of the industry, as the federal government poured billions of dollars of public money into the construction of interstate highways and airports, and ended the haulage of mail by the rails, which led to the discontinuance of hundreds of passenger trains, and with them went the jobs of those who ran and serviced the trains. Starved for cash by the late 1950s, many railroads declared bankruptcy.

Nationwide and in Pennsylvania, the health of the industry did not return until, again, action came at the federal level. Faced with a choice of liquidation of the railroads, nationalization, or a restoration of private enterprise, Congress chose the latter, passing the Staggers Rail Act of 1980, which began to restore the economic health of the industry. At the dawn of the twenty-first century the American railroad industry employed only 220,000 workers, one-ninth of the number in 1920.