Chapter One: Pennsylvania Art: From Its Beginnings to the Late Nineteenth Century

From the time William Penn settled Pennsylvania until the Battle of Gettysburg, the events and people of Pennsylvania were among the best known in the United States. Penn's founding of Pennsylvania, the Revolutionary War, America's bountiful and beautiful plants, animals, and sceneries, a democratic populace exercising its newly found economic and political power, and the heroism and horror of the Civil War all entered the nation's collective memory, in large part, through Pennsylvania art. For instance, after

Aside from Hicks, few artists celebrated Pennsylvania's three-quarters of a century as a peaceful refuge for people of different religions. The Quakers, for instance, shunned depiction of the human image as a sign of vanity - the only surviving portrait of the adult William Penn is a sketch he did not know was being made. One notable exception, unlike any other painting in colonial America, is Moravian Johan Valentine Haidt's (1700-1766) "The First Fruits." Painted between 1755 and 1760, this extraordinary work celebrates the Moravians' worldwide missionary efforts through realistic and sympathetic images of Asians, Africans, and American Indians who approach the throne of God. Haidt's work is displayed in the equally exceptional Moravian settlement at Bethlehem, founded in the 1740s, whose architecture is distinctive in British North America.

Unlike the Amish, the German Brethren at the Ephrata Cloister, and other pacifist German groups who came to Pennsylvania were not primarily poor farmers and craftsmen. These latecomers to Pennsylvania's diverse religious landscape included sophisticated, well-trained artists and musicians. Moravians were among the German immigrant groups that practiced the folk art of

Far more artists celebrated the young American republic. Notable among them was

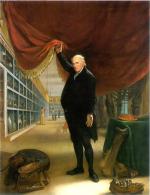

In this painting, Peale presents America by depicting both its nature and republican founders, in an orderly manner, with men placed above animals. The new republic itself, he is saying, does not represent the anarchy Europeans feared; as the well-mannered family inspecting the exhibits suggests, not only can the United State produce superior animal and human specimens (revolutionary heroes) to Europe, it can incorporate them into a refined and orderly national space, which Peale's museum represents in miniature. Peale was at the head of another artistic world, too; several sons, to whom he gave the names of the great masters Rembrandt, Raphaelle, Rubens, and Titian, and two daughters, Sarah Miriam and Anna Claypoole, followed in his footsteps.

Peale celebrated a heroic America. Well into the1800s, Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze,

The early nineteenth century also witnessed the rise of "genre" painters, who celebrated another sort of hero - "the common man" (and woman) - as worthy heirs of the founding generation. John Lewis Krimmel, a German immigrant who worked in Philadelphia, was one of the best. He is most famous for the energy displayed by the bustling crowds he portrayed in public spaces. In works such as "Fourth of July in Central Square" (1812) and "Election Day at the State House" (1815), a large number of people young and old, rich and poor, black and white, male and female, and even dogs, are all given individual, positive identities. Krimmel did not share French observer Alexis de Tocqueville's belief that Democracy in America (the title of his great 1831 commentary) would stifle individuality and creativity, but rather that this new nation unleashed the hitherto unrevealed potential of ordinary folks.

Other genre artists painted portraits of successful working-class individuals, who claimed artistic equality with the upper-class people who had their own and their families' portraits painted in the colonial period and early republic (See Benjamin West's portrait of Thomas Mifflin, for example, which inspired Philadelphians to send him to Europe).

In many of these works, it was customary to place something indicating the subject's occupation or career in the background: a bolt of lightning for Benjamin Franklin, a ship for a merchant or sea captain, and a gun, dead game, and beautiful estate for West's young Mifflin, for example. Painted in 1829, John Neagle's "Pat Lyon at the Forge" shows a confident, likeable, well-to-do blacksmith. Only those who knew Lyon's biography and Philadelphia architecture would notice that the local jail, where he had briefly served time for debt, is the background object that Neagle used to identify the obstacles that Lyon had overcome in his youth.

Pennsylvania's beautiful landscapes were another cause for artistic celebration. The early work of Thomas Doughty, George Hetzel, and Thomas Moran conveyed early nineteenth-century Americans' belief that nature was omnipresent and inexhaustible (Moran painted Wissahickon Creek near Philadelphia before he became the premier landscape artist of the American West). In perhaps the most famous Pennsylvania landscape, "The Lackawanna Valley," George Inness showed the changes in the American landscape then being wrought by the railroad. To the executives of the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad who commissioned it, as to most contemporary audiences, the railroad and roundhouse perfected rather than spoiled the landscape.

But the impact of the "machine" on the "garden" was not without a cost, or its critics. If

Another important Pennsylvania landscape artist,

In his canvasses, Pittsburgh's David Gilmour Blythe (1815-1865) expressed his feelings about the nature of America and its future. In two paintings of the Pittsburgh Post Office, he portrayed the excessively competitive and faceless society that Tocqueville feared was developing in the young Republic. On one canvas, his loafing subjects plan what appears to be criminal activity. Their faces are neither well defined or individually distinctive. On the other canvas, they compete to see who can get their mail first. With their backs to us, the painting is dominated by a woman's ballooning hoop skirt. As with economic opportunity, the door through which all would pass was far too narrow to accommodate all applicants. After the Civil War, Pennsylvania's art would continue to reflect a nation in which new technologies and rapid industrialization were creating both vast wealth and great inequalities.