![header=[Marker Text] body=[The renowned poet was born here on September 10, 1886; died in Zurich, September 27, 1961. H. D. sought the Hellenic spirit and a classic beauty of expression. She is buried in nearby Nisky Hill Cemetery. "O, give me burning blue."] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-3F6-139-Doolittle.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

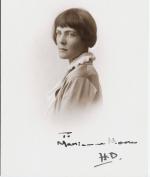

Hilda Doolittle (H.D.)

County:

Northampton

Marker Location:

10 E. Church St., City Center Plaza, Bethlehem

Dedication Date:

September 1982

Behind the Marker

As a writer, Hilda Doolittle remains better known than read, her legacy built more on the largeness of her life than on the deft precision of her verse. A daring experimenter both on and off the page, H. D. led the Imagist movement she was tremendously influential over a generation of poets who rose out of World War I.

Decades ahead of her time, Doolittle unabashedly tested the boundaries of human sexuality, entered into psychoanalysis with Freud himself, sought counsel from pioneering sexologist Havelock Ellis, and over a long and prolific career used her poetry and often brutally frank prose to examine and redefine women's roles in ways that turned her, after her death, into a beacon for the burgeoning feminist and gay-rights movements.

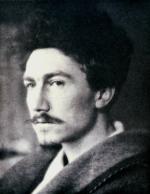

Her friends included D.H. Lawrence, James Joyce, William Carlos Williams and Marianne Moore. Engaged to Ezra Pound, perhaps the most controversial character in twentieth-century letters, she lived on and off for forty years with Annie Winifred Ellerman, the cigar-smoking heiress and novelist who wrote under the name of Bryher. As avant garde as Doolittle could be, she consistently reached back to Greek lore and literature for inspiration, symbolism, and solace.

Marianne Moore. Engaged to Ezra Pound, perhaps the most controversial character in twentieth-century letters, she lived on and off for forty years with Annie Winifred Ellerman, the cigar-smoking heiress and novelist who wrote under the name of Bryher. As avant garde as Doolittle could be, she consistently reached back to Greek lore and literature for inspiration, symbolism, and solace.

Doolittle was born in 1886 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where her father, Charles Doolittle, was an astronomy professor at Lehigh University, and her mother, Helen Wolle Doolittle, taught music and painting at the Moravian Seminary. When Hilda was ten, her father was appointed Flower Professor of Astronomy and director of the Flower Observatory at the University of Pennsylvania, and the family moved to Philadelphia's Main Line.

Charles Doolittle wanted his only daughter to become a scientist. Actively discouraging her early explorations of the arts, he tutored her daily, hoping to create another Marie Curie, but, his daughter later wrote, "The more he explained, the less I understood." Her half-brother Eric introduced her to worlds built by writers like Louisa May Alcott, Jane Austen, and the Bronte sisters, all of whom captured her imagination. So too did a Penn student who liked visiting her father's observatory; she met and fell in love with Ezra Pound when she was just fifteen.

When she entered Bryn Mawr to study Classics in 1905, Pound gathered the love poems he had written her into a collection he called Hilda's Book. The two grew closer. She also became friendly with fellow student Marianne Moore, and Pound's classmate William Carlos Williams, both of whom would later rise to prominence as poets. Until poor grades and ill health forced Doolittle to leave school in 1907, the four met regularly to talk about literature and poetry and the need to modernize them for the new century.

Over her father's strenuous objection, Doolittle and Pound became engaged that year, but by the next, with Pound in Europe blazing his unique modernist trail and Doolittle conflicted by the very notion of marriage, the engagement ended. She began publishing poems and stories in small journals and newspapers, and fell into her first serious relationship with a woman, Frances Gregg. In 1911, the two sailed for a summer vacation to London. Doolittle, in essence, never came back.

In London, she reconnected with Pound, who ushered her into his growing literary circle, which included Ford Maddox Ford, William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, and Richard Aldington. Already established as an important new voice, Pound liked what he saw of Doolittle's writing, and was impressed with how much it naturally fit into the poetic ideals-economy of language, precision of image, and the natural rhythms of speech-that he and Aldington had begun expounding. In 1912, the three asserted themselves as the "three original Imagists." During a meeting at the tearoom of the British Museum, Pound was especially taken by the poems Doolittle showed him. "It's straight talk," he exclaimed, "straight as Greek," and it was. Just witness the opening of "Hermes of the Ways," its language void of any excess:

The hard sand breaks,

Enthralled, Pound selected three poems, scratched the name "H.D. Imagiste" on them, and submitted them to the prestigious American magazine Poetry, which published them. Doolittle embraced those genderless initials and the opportunity to abandon the ambitionless sound of her last name. Although she quickly dropped the Imagiste, she from then on signed her work as H.D.

In 1913, she married Aldington, and in 1914 saw her work included, along with Pound's, Yeats's, Aldington's, and Joyce's, in the first Imagist anthology. The following year, she and Aldington, who loved classical literature and Greek myth as much as his wife, embarked on a series of translations from Greek and Latin classics that she would continue long after the marriage ended.

In 1916, H.D. published Sea Garden, the first of her more than a dozen books of poetry, which cemented her growing reputation as an important new voice. Her message, in poems like "Pear Tree,"

"Pear Tree,"  "Sheltered Garden," and

"Sheltered Garden," and  "Sea Rose," was pointed: the florid conventions of poetry's past must give way to a cleaner modernism. Then, when Aldington enlisted into the Army in World War I, she replaced him as editor of the influential literary magazine The Egoist.

"Sea Rose," was pointed: the florid conventions of poetry's past must give way to a cleaner modernism. Then, when Aldington enlisted into the Army in World War I, she replaced him as editor of the influential literary magazine The Egoist.

Her next several years were trying. Her half-brother Eric was killed fighting in France; she suffered two miscarriages; she grew apart from her husband; and her father died. In 1919 she gave birth to her only child, Perdita, but that, too, was complicated. Although Aldington was listed as the father, the child's real father was English composer Cecil Gray, with whom H.D. had briefly lived. In 1918, she met Bryher, who had written H.D. an admiring fan letter; they would live together until 1946 and remain deeply committed to each other until H.D.'s death in 1961, though each would take other partners along their route, and, occasionally, even share the same men.

After the war, they travelled widely through Egypt, Greece, and the United States, and, in 1924, moved to in Switzerland. For H.D., the time between the wars was creatively fertile, although not altogether critically satisfying. She continued to stretch and push her poetic voice in Translations (1920), Hymen (1921), Heliodora and Other Poems (1924), Collected Poems, (1925), Red Roses From Bronze (1932), and the 1927 verse drama Hippolytus Temporizes.

H.D. also turned to prose to explore themes of feminism and the role of the artist in three experimental works of fiction, most notably HERmione, a thinly-veiled roman … clef built around her life between Bryn Mawr and London that had remained squirreled away until after her death. In 1930, she appeared with Paul Robeson in "Borderline," a silent movie about racial prejudice, and she underwent analysis with Sigmund Freud, later revisiting the experience in a fascinating memoir, Tribute to Freud, with Unpublished Letters to Freud by the Author (1956).

Paul Robeson in "Borderline," a silent movie about racial prejudice, and she underwent analysis with Sigmund Freud, later revisiting the experience in a fascinating memoir, Tribute to Freud, with Unpublished Letters to Freud by the Author (1956).

As World War II broke out, she and Bryher returned to London, where H.D. published three well-received volumes of poetry-The Walls Do Not Fall (1943), Tribute to the Angels (1945) and Flowering of the Rod (1946)-that became collectively known as the "War Trilogy." Returning to prose, she also penned a memoir, The Gift, about growing up in Pennsylvania and the formative events that influenced her writing. Unpublished until 1960, it opens stunningly: "There was a girl who was burnt to death at the Seminary, as they called the old school where our grandfather was buried."

After the war, H.D. returned to Switzerland, where she continued pushing the boundaries of her poetry. In her epic poem "Helen in Egypt," she reexamined the Trojan War from a feminist perspective, and in the posthumously published memoir End to Torment, she opened the window on her relationship with Pound, who allowed inclusion of the poems that made up Hilda's Book.

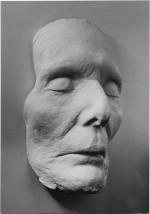

In 1960, H.D. returned to the United States when she was named the first woman recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters medal. She died in Switzerland the following year, and her ashes were buried in the family plot in Bethlehem, near the Seminary where the girl in the first sentence of The Gift had been burned to death.

Decades ahead of her time, Doolittle unabashedly tested the boundaries of human sexuality, entered into psychoanalysis with Freud himself, sought counsel from pioneering sexologist Havelock Ellis, and over a long and prolific career used her poetry and often brutally frank prose to examine and redefine women's roles in ways that turned her, after her death, into a beacon for the burgeoning feminist and gay-rights movements.

Her friends included D.H. Lawrence, James Joyce, William Carlos Williams and

Doolittle was born in 1886 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where her father, Charles Doolittle, was an astronomy professor at Lehigh University, and her mother, Helen Wolle Doolittle, taught music and painting at the Moravian Seminary. When Hilda was ten, her father was appointed Flower Professor of Astronomy and director of the Flower Observatory at the University of Pennsylvania, and the family moved to Philadelphia's Main Line.

Charles Doolittle wanted his only daughter to become a scientist. Actively discouraging her early explorations of the arts, he tutored her daily, hoping to create another Marie Curie, but, his daughter later wrote, "The more he explained, the less I understood." Her half-brother Eric introduced her to worlds built by writers like Louisa May Alcott, Jane Austen, and the Bronte sisters, all of whom captured her imagination. So too did a Penn student who liked visiting her father's observatory; she met and fell in love with Ezra Pound when she was just fifteen.

When she entered Bryn Mawr to study Classics in 1905, Pound gathered the love poems he had written her into a collection he called Hilda's Book. The two grew closer. She also became friendly with fellow student Marianne Moore, and Pound's classmate William Carlos Williams, both of whom would later rise to prominence as poets. Until poor grades and ill health forced Doolittle to leave school in 1907, the four met regularly to talk about literature and poetry and the need to modernize them for the new century.

Over her father's strenuous objection, Doolittle and Pound became engaged that year, but by the next, with Pound in Europe blazing his unique modernist trail and Doolittle conflicted by the very notion of marriage, the engagement ended. She began publishing poems and stories in small journals and newspapers, and fell into her first serious relationship with a woman, Frances Gregg. In 1911, the two sailed for a summer vacation to London. Doolittle, in essence, never came back.

In London, she reconnected with Pound, who ushered her into his growing literary circle, which included Ford Maddox Ford, William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, and Richard Aldington. Already established as an important new voice, Pound liked what he saw of Doolittle's writing, and was impressed with how much it naturally fit into the poetic ideals-economy of language, precision of image, and the natural rhythms of speech-that he and Aldington had begun expounding. In 1912, the three asserted themselves as the "three original Imagists." During a meeting at the tearoom of the British Museum, Pound was especially taken by the poems Doolittle showed him. "It's straight talk," he exclaimed, "straight as Greek," and it was. Just witness the opening of "Hermes of the Ways," its language void of any excess:

The hard sand breaks,

and the grains of it

are clear as wine.

Far off over, the leagues of it,

the wind,

playing on the wide shore,

piles little ridges,

and the great waves

break over it.

are clear as wine.

Far off over, the leagues of it,

the wind,

playing on the wide shore,

piles little ridges,

and the great waves

break over it.

Enthralled, Pound selected three poems, scratched the name "H.D. Imagiste" on them, and submitted them to the prestigious American magazine Poetry, which published them. Doolittle embraced those genderless initials and the opportunity to abandon the ambitionless sound of her last name. Although she quickly dropped the Imagiste, she from then on signed her work as H.D.

In 1913, she married Aldington, and in 1914 saw her work included, along with Pound's, Yeats's, Aldington's, and Joyce's, in the first Imagist anthology. The following year, she and Aldington, who loved classical literature and Greek myth as much as his wife, embarked on a series of translations from Greek and Latin classics that she would continue long after the marriage ended.

In 1916, H.D. published Sea Garden, the first of her more than a dozen books of poetry, which cemented her growing reputation as an important new voice. Her message, in poems like

Her next several years were trying. Her half-brother Eric was killed fighting in France; she suffered two miscarriages; she grew apart from her husband; and her father died. In 1919 she gave birth to her only child, Perdita, but that, too, was complicated. Although Aldington was listed as the father, the child's real father was English composer Cecil Gray, with whom H.D. had briefly lived. In 1918, she met Bryher, who had written H.D. an admiring fan letter; they would live together until 1946 and remain deeply committed to each other until H.D.'s death in 1961, though each would take other partners along their route, and, occasionally, even share the same men.

After the war, they travelled widely through Egypt, Greece, and the United States, and, in 1924, moved to in Switzerland. For H.D., the time between the wars was creatively fertile, although not altogether critically satisfying. She continued to stretch and push her poetic voice in Translations (1920), Hymen (1921), Heliodora and Other Poems (1924), Collected Poems, (1925), Red Roses From Bronze (1932), and the 1927 verse drama Hippolytus Temporizes.

H.D. also turned to prose to explore themes of feminism and the role of the artist in three experimental works of fiction, most notably HERmione, a thinly-veiled roman … clef built around her life between Bryn Mawr and London that had remained squirreled away until after her death. In 1930, she appeared with

As World War II broke out, she and Bryher returned to London, where H.D. published three well-received volumes of poetry-The Walls Do Not Fall (1943), Tribute to the Angels (1945) and Flowering of the Rod (1946)-that became collectively known as the "War Trilogy." Returning to prose, she also penned a memoir, The Gift, about growing up in Pennsylvania and the formative events that influenced her writing. Unpublished until 1960, it opens stunningly: "There was a girl who was burnt to death at the Seminary, as they called the old school where our grandfather was buried."

After the war, H.D. returned to Switzerland, where she continued pushing the boundaries of her poetry. In her epic poem "Helen in Egypt," she reexamined the Trojan War from a feminist perspective, and in the posthumously published memoir End to Torment, she opened the window on her relationship with Pound, who allowed inclusion of the poems that made up Hilda's Book.

In 1960, H.D. returned to the United States when she was named the first woman recipient of the American Academy of Arts and Letters medal. She died in Switzerland the following year, and her ashes were buried in the family plot in Bethlehem, near the Seminary where the girl in the first sentence of The Gift had been burned to death.