![header=[Marker Text] body=[Eminent poet, editor, essayist, and teacher. Her independent spirit and keen eye for detail distinguished her life and work. Moore won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature, the Bollingen Prize in Poetry, and the National Book Award. She lived here (1896–1916).] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-3F5-139-Moore.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

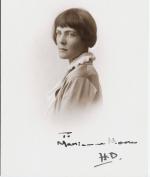

Marianne Moore

Region:

Hershey/Gettysburg/Dutch Country Region

County:

Cumberland

Marker Location:

343 N Hanover Street, Carlisle

Dedication Date:

April 25, 2002

Behind the Marker

As poets go, Marianne Moore’s credentials were impeccable. Her poems appeared in the most distinguished publications, and she received the principal honors her profession bestowed. T.S. Eliot said that her "poems form part of the small body of durable poetry written in our time." W.H. Auden happily volunteered that he borrowed from her frequently. High praise, indeed, for a writer inclined to describe herself as “a happy hack.”

But this is just a hint of the mark Moore left both on her craft and in the public mind. A leading proponent of the Imagist movement that eschewed the ornate language of Victorian literature for something closer to common speech, Moore helped shape the voice of twentieth-century American poetry, and the very idea of the twentieth-century American poet. With her tricorne hat atop her long, gray braid, and a cape that embraced her willowy frame, she was an unmistakable presence, as much a part of the nation’s popular culture as its literary avant-garde. Her personality radiated, as did her self-effacing humor. "I’m all bone, just solid, pure bone," she said of herself. "I’m good natured, but hideous as an old hoptoad."

Moore was a regular on TV talk shows, at chic parties and fashion shows, at lectures, concerts, ballgames, and even the occasional boxing match. In her seventies, she graced the cover of Esquire. At eighty, she opened the baseball season by throwing out the first pitch at Yankee Stadium. Her circle was wide enough to include e.e. cummings and Casey Stengel. She was truly one of a kind.

Marianne Moore grew up outside St. Louis, where she was born, in 1887. She never met her father; he had suffered a severe breakdown shortly before her birth and was institutionalized in Massachusetts. Pregnant with Marianne, her mother returned to Missouri to live with her father, a Presbyterian minister. When he died in 1894, Mary Moore—a strong, overprotective presence in her daughter’s life for the next fifty years—moved Marianne and her older brother to Pennsylvania, eventually settling in Carlisle. There, Marianne excelled in school, and, in 1905, was admitted to the elite Bryn Mawr College on Philadelphia’s Main Line.

At Bryn Mawr, Moore majored in biology, briefly considering the idea of a career in medicine until she was drawn to modernist literature. Founded in 1885, Bryn Mawr thrived under its first female president, Martha Carey Thomas. Under her leadership, from 1894 to 1922, it became one of the most elite, academically rigorous, and progressive women’s schools in the country. Centered on a classical curriculum with grounding in Greek, Latin, and the classics, it rivaled the best universities in the country. The first college to offer graduate fellowships to women, Bryn Mawr had a tremendous impact on the lives of its many of its all-female students, who included Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Margaret Ayres Barnes (1907), children’s-book writer Cornelia Lynde Meigs (1908), classicist Lily Ross Taylor (1912), and New Yorker editor Katharine Sergeant Angell White (1914).

Moore published several of her own poems in the college’s two literary magazines, including "Ennui" and "Progress," both printed in Tipyn O’Bob in 1909. It was also at this time that Moore first met Hilda Doolittle, who would become one of her literary mentors. Moore’s years at Bryn Mawr marked a critical time in her life; it was there she first received recognition as a writer and began to expand her artistic form. Through her studies and interactions with students and faculty, she developed a sense of self- and social awareness, taking interest in the suffrage movement and the relationship between socialism and the arts.

Hilda Doolittle, who would become one of her literary mentors. Moore’s years at Bryn Mawr marked a critical time in her life; it was there she first received recognition as a writer and began to expand her artistic form. Through her studies and interactions with students and faculty, she developed a sense of self- and social awareness, taking interest in the suffrage movement and the relationship between socialism and the arts.

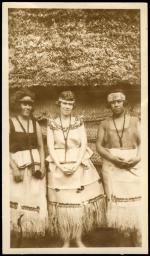

After graduation in 1909, Moore returned to Carlisle, took some commercial business courses, and then joined her mother for a grand cultural tour of England, Scotland, and France. Back in Carlisle, she taught stenography at the Carlisle Indian School from 1911 to 1915. There, one of her students was the great athlete

Carlisle Indian School from 1911 to 1915. There, one of her students was the great athlete  Jim Thorpe.

Jim Thorpe.

At Carlisle, Moore continued to develop her literary style and entered the most active period of her career, publishing fifty-one poems between the 1910 and 1917. In 1915, Doolittle, now settled in London, wrote to Moore after her husband accepted several of Moore’s poems for publication in the influential bimonthly, The Egoist, initiating their decades long friendship. Soon, Moore and her mother took an apartment in New York’s bohemian capital, Greenwich Village. Moore began working as an assistant librarian in the city’s public library system. More importantly, she found a place for herself and her poetry in a downtown literary circle that included William Carlos Williams and Wallace Stevens. There, too, Ezra Pound started a correspondence with her, which eventually blossomed into to a remarkable literary friendship.

Wallace Stevens. There, too, Ezra Pound started a correspondence with her, which eventually blossomed into to a remarkable literary friendship.

Without Moore’s knowledge, Doolittle in 1921 published a book of twenty-four of Moore’s verses, called, simply, Poems, in London. Both Poems and her second collection, Observations (1924), reaped critical acclaim. Moore also received a $2,000 award from the prestigious pro-modernist journal, The Dial, which allowed Moore to leave the library to become editor of The Dial, a title she kept until the magazine closed in 1929. That year, Moore and her mother left Manhattan for Fort Greene, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. Moore remained a Brooklynite, living in the same book-filled apartment until 1966.

Moore published her next book, Selected Poems, with an introduction by Eliot, in 1935; Pangolin in 1936; What Are Years in 1941; then several more short collections, plus essays, and a celebrated 1954 verse translation, Fables of La Fontaine. In 1951, Collected Poems won poetry’s triple crown: the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the Bollingen Prize.

Moore was not a prolific writer. The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore, published to coincide with her eightieth birthday in 1967, contained just 120 poems in just over 242 pages. She was, however, a painstakingly careful writer, always revising, as if picking and re-picking her words with, as one critic said, tweezers. A precise observer, she loved the rhythm of poetry, and the majesty of simple words, which she stitched together in compact, if intricate, patterns. "I admire the legerdemain of saying a lot in a few words," she explained— with very specific rhythmic schemes based on a predetermined number of syllables per line.

Moore demanded much from readers: "It ought to be work to read something that was work to write," she insisted. And whether focused on baseball. which she loved unconditionally, or

on baseball. which she loved unconditionally, or  poetry itself, her work tapped into both her wit and intellect. She regularly

poetry itself, her work tapped into both her wit and intellect. She regularly  used animals as subjects to drive her philosophic arguments across more gently. Indeed, she took much of her poetic imagery from the natural world she had studied so intently in college. Some critics ascribed a cool detachment to the complexities of her verse, while others, like the noted critic Louise Bogan, saw Moore as "a naturalist without pedantry, and a moralist without harshness."

used animals as subjects to drive her philosophic arguments across more gently. Indeed, she took much of her poetic imagery from the natural world she had studied so intently in college. Some critics ascribed a cool detachment to the complexities of her verse, while others, like the noted critic Louise Bogan, saw Moore as "a naturalist without pedantry, and a moralist without harshness."

In the 1950s, she relished the very public assignment she took from the Ford Motor Company to come up with a name for a new series of cars. Her ideas ranged from the fanciful—The Intelligent Whale, The Turtlestopper, and The Ford Faberge—to the high-throttled—The Ford Silver Sword, The Resilient Bullet, and Hurricane Hirundo. Ford, instead, opted for what turned into a snakebit moniker of its own choosing: The Edsel. In the 1960s, she relished another assignment: writing the liner notes to heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali’s album of verse, I Am the Greatest!

Shortly before her death in 1972, Moore sold her papers, both personal and literary, to Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum and Library. In her will, she also left the museum her furniture and other belongings. Her Greenwich Village living room, complete with velvet couches and one of her tricorne hats, is part of the Rosenbach’s permanent display.

But this is just a hint of the mark Moore left both on her craft and in the public mind. A leading proponent of the Imagist movement that eschewed the ornate language of Victorian literature for something closer to common speech, Moore helped shape the voice of twentieth-century American poetry, and the very idea of the twentieth-century American poet. With her tricorne hat atop her long, gray braid, and a cape that embraced her willowy frame, she was an unmistakable presence, as much a part of the nation’s popular culture as its literary avant-garde. Her personality radiated, as did her self-effacing humor. "I’m all bone, just solid, pure bone," she said of herself. "I’m good natured, but hideous as an old hoptoad."

Moore was a regular on TV talk shows, at chic parties and fashion shows, at lectures, concerts, ballgames, and even the occasional boxing match. In her seventies, she graced the cover of Esquire. At eighty, she opened the baseball season by throwing out the first pitch at Yankee Stadium. Her circle was wide enough to include e.e. cummings and Casey Stengel. She was truly one of a kind.

Marianne Moore grew up outside St. Louis, where she was born, in 1887. She never met her father; he had suffered a severe breakdown shortly before her birth and was institutionalized in Massachusetts. Pregnant with Marianne, her mother returned to Missouri to live with her father, a Presbyterian minister. When he died in 1894, Mary Moore—a strong, overprotective presence in her daughter’s life for the next fifty years—moved Marianne and her older brother to Pennsylvania, eventually settling in Carlisle. There, Marianne excelled in school, and, in 1905, was admitted to the elite Bryn Mawr College on Philadelphia’s Main Line.

At Bryn Mawr, Moore majored in biology, briefly considering the idea of a career in medicine until she was drawn to modernist literature. Founded in 1885, Bryn Mawr thrived under its first female president, Martha Carey Thomas. Under her leadership, from 1894 to 1922, it became one of the most elite, academically rigorous, and progressive women’s schools in the country. Centered on a classical curriculum with grounding in Greek, Latin, and the classics, it rivaled the best universities in the country. The first college to offer graduate fellowships to women, Bryn Mawr had a tremendous impact on the lives of its many of its all-female students, who included Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Margaret Ayres Barnes (1907), children’s-book writer Cornelia Lynde Meigs (1908), classicist Lily Ross Taylor (1912), and New Yorker editor Katharine Sergeant Angell White (1914).

Moore published several of her own poems in the college’s two literary magazines, including "Ennui" and "Progress," both printed in Tipyn O’Bob in 1909. It was also at this time that Moore first met

After graduation in 1909, Moore returned to Carlisle, took some commercial business courses, and then joined her mother for a grand cultural tour of England, Scotland, and France. Back in Carlisle, she taught stenography at the

At Carlisle, Moore continued to develop her literary style and entered the most active period of her career, publishing fifty-one poems between the 1910 and 1917. In 1915, Doolittle, now settled in London, wrote to Moore after her husband accepted several of Moore’s poems for publication in the influential bimonthly, The Egoist, initiating their decades long friendship. Soon, Moore and her mother took an apartment in New York’s bohemian capital, Greenwich Village. Moore began working as an assistant librarian in the city’s public library system. More importantly, she found a place for herself and her poetry in a downtown literary circle that included William Carlos Williams and

Without Moore’s knowledge, Doolittle in 1921 published a book of twenty-four of Moore’s verses, called, simply, Poems, in London. Both Poems and her second collection, Observations (1924), reaped critical acclaim. Moore also received a $2,000 award from the prestigious pro-modernist journal, The Dial, which allowed Moore to leave the library to become editor of The Dial, a title she kept until the magazine closed in 1929. That year, Moore and her mother left Manhattan for Fort Greene, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. Moore remained a Brooklynite, living in the same book-filled apartment until 1966.

Moore published her next book, Selected Poems, with an introduction by Eliot, in 1935; Pangolin in 1936; What Are Years in 1941; then several more short collections, plus essays, and a celebrated 1954 verse translation, Fables of La Fontaine. In 1951, Collected Poems won poetry’s triple crown: the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the Bollingen Prize.

Moore was not a prolific writer. The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore, published to coincide with her eightieth birthday in 1967, contained just 120 poems in just over 242 pages. She was, however, a painstakingly careful writer, always revising, as if picking and re-picking her words with, as one critic said, tweezers. A precise observer, she loved the rhythm of poetry, and the majesty of simple words, which she stitched together in compact, if intricate, patterns. "I admire the legerdemain of saying a lot in a few words," she explained— with very specific rhythmic schemes based on a predetermined number of syllables per line.

Moore demanded much from readers: "It ought to be work to read something that was work to write," she insisted. And whether focused

In the 1950s, she relished the very public assignment she took from the Ford Motor Company to come up with a name for a new series of cars. Her ideas ranged from the fanciful—The Intelligent Whale, The Turtlestopper, and The Ford Faberge—to the high-throttled—The Ford Silver Sword, The Resilient Bullet, and Hurricane Hirundo. Ford, instead, opted for what turned into a snakebit moniker of its own choosing: The Edsel. In the 1960s, she relished another assignment: writing the liner notes to heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali’s album of verse, I Am the Greatest!

Shortly before her death in 1972, Moore sold her papers, both personal and literary, to Philadelphia’s Rosenbach Museum and Library. In her will, she also left the museum her furniture and other belongings. Her Greenwich Village living room, complete with velvet couches and one of her tricorne hats, is part of the Rosenbach’s permanent display.