![header=[Marker Text] body=[German-born inventor and showman; exhibited nearby at Maelzel's Hall, 1826-1831, assisted by Wm. Schlumberger. His Automaton Chess Player (The Turk) was famous for games with Franklin and Napoleon. He patented a metronome; made hearing aids for Beethoven.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-397-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0m4m9-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

John Nepomuk Maelzel

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

NW corner of Fifth St. and St. Mark's St., Philadelphia

Dedication Date:

July 5, 2004

Behind the Marker

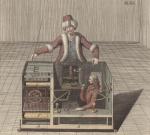

On December 26, 1826, excited Philadelphians gathered at the Masonic Hall on Chestnut Street between Seventh and Eighth streets. The crowd was hushed when the suave European "prince of entertainers," John Maelzel, stepped onto the stage and wheeled out "The Turk." Seated at its own desk, draped in a green silk robe and a turban, The Turk was billed as a thinking machine that played chess.

To prove that it was not human, Maelzel unlocked and opened its doors to reveal belts, cogs, and gears. Next, he set up the chessboard and selected an audience member to play against the device. Then Maelzel wound up The Turk. It made a loud ratcheting sound. When the human challenger moved a piece, the machine suddenly jerked to life. Its arm and hand moved forward, and its fingers gently grasped a piece and moved it.

The Turk was a good chess player. More often than not, it won. It could also recognize and correct illegal or improper moves and even uttered "checkmate" in French (chec et mat) when it won the opponent's king. The Turk made a lasting impression on all who saw it. Years later, the renowned Philadelphia physician Silas Weir Mitchell recalled how The Turk had haunted his boyhood dreams.

When Maelzel arrived in New York City in 1826, he hoped he had left his troubles behind him in Europe. First, he was deeply in debt. Second, he did not own The Turk. He had sold the machine in 1809 to Eugene de Beauharnais, Napoleon's stepson, but then repented. Unable to repurchase it, Maelzel leased it from de Beauharnais, and then fell behind on the payments. He also falsely claimed to have invented the "Maelzel Metronome," when in fact he had misappropriated the design from a Dutch inventor who was suing him.

After a few months in New York and Boston, Maelzel settled in Philadelphia. In the Quaker city, he rented a building, hired workers to renovate the space, advertised, and assisted by his secretary William Schlumberger, assembled his automata. Amusing and often educational machines, automata had been common in Europe for decades. Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen, a counselor to Austro-Hungarian Empress Maria Theresa, had constructed The Turk back in 1769. Its arrival in the United States created the sensation, and profits, no longer available in Europe. For eleven years, Maelzel and his troupe toured the nation, visiting New York City, Boston, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Richmond, Charleston, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Louisville, and New Orleans.

Everyone marveled at The Turk and wondered how it worked. Was it evidence of a future dominated by machines? Could The Turk think? If so, was this good, natural, moral? Or was The Turk a hoax? Observers hazarded various answers to those questions. Edgar Allan Poe saw The Turk several times, and like some European critics, concluded that a

saw The Turk several times, and like some European critics, concluded that a  person "concealed in the box" controlled the device. Others were convinced that it was a thinking machine. Maelzel was amused by all of the speculation, but kept his counsel.

person "concealed in the box" controlled the device. Others were convinced that it was a thinking machine. Maelzel was amused by all of the speculation, but kept his counsel.

In late 1837, Maelzel and his troupe made a second trip to Cuba for an extended stay. There, Maelzel suffered a series of misfortunes: attendance dropped and the show lost money, Schlumberger died of yellow fever, and his assistants abandoned him. Alone, broke and depressed, Maelzel borrowed enough money to return to Philadelphia, where he planned to open a new show. He died at sea, however, and his body was cast overboard off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, on July 21, 1838. His automata and other belongings were auctioned in Philadelphia to pay his creditors.

The Turk's new owner, Dr. John Kearsley Mitchell (father of frightened Silas), lacked Maelzel's panache and showmanship skills. Public interest in the "Automaton Chess Player" waned dramatically, so in 1840 Mitchell donated the machine to Nathan Dunn's "Chinese Museum" at Ninth and George (now Sansom) streets, where it was largely forgotten, and then destroyed by fire on July 5, 1854.

So what was The Turk's secret? Maelzel's famous Automaton Chess Player was, in fact, a clever hoax; Schulmberger operated it from inside the cabinet. He avoided detection by moving forward or backward on a sliding seat when the cabinet doors were opened in proper sequence. The history of American entertainment is filled with similar ploys. P.T. Barnum-who had met Maelzel in 1835 and been advised by the German to make good use of the press-was famous for humbugs like "the man in the moon" and the "FeeJee mermaid."

The Turk, however, did more than amuse people. It prompted some thoughtful Americans to ask profound questions about the relationship between science and religion, and the potential of science to change the world. Mary Shelley also examined these questions in her novel Frankenstein,a book read by many Americans after its American publication in Philadelphia in 1831.

The mystery behind The Turk also fueled the growing fascination with machines. American life and culture were in the process of being revolutionized by steam engines, locomotives, steamboats, and the telegraph. Artificial intelligence seemed like the next step. Within a century, it was a reality. In 1946 scientists working at the University of Pennsylvania developed ENIAC, the world's first electronic digital computer.

ENIAC, the world's first electronic digital computer.

Three years later, electrical engineer and mathematician Dr. Claude Shannon built another Turk, the first computer to play chess. In tests reminiscent of Maelzel's exhibitions, engineers and scientists used chess to compare the capabilities of humans and computers. Humans consistently beat their mechanical opponents until 1997, when IBM's Turk, "Deep Blue," defeated international chess master Gary Kasparov in a match that Maelzel, no doubt, would have enjoyed.

To prove that it was not human, Maelzel unlocked and opened its doors to reveal belts, cogs, and gears. Next, he set up the chessboard and selected an audience member to play against the device. Then Maelzel wound up The Turk. It made a loud ratcheting sound. When the human challenger moved a piece, the machine suddenly jerked to life. Its arm and hand moved forward, and its fingers gently grasped a piece and moved it.

The Turk was a good chess player. More often than not, it won. It could also recognize and correct illegal or improper moves and even uttered "checkmate" in French (chec et mat) when it won the opponent's king. The Turk made a lasting impression on all who saw it. Years later, the renowned Philadelphia physician Silas Weir Mitchell recalled how The Turk had haunted his boyhood dreams.

When Maelzel arrived in New York City in 1826, he hoped he had left his troubles behind him in Europe. First, he was deeply in debt. Second, he did not own The Turk. He had sold the machine in 1809 to Eugene de Beauharnais, Napoleon's stepson, but then repented. Unable to repurchase it, Maelzel leased it from de Beauharnais, and then fell behind on the payments. He also falsely claimed to have invented the "Maelzel Metronome," when in fact he had misappropriated the design from a Dutch inventor who was suing him.

After a few months in New York and Boston, Maelzel settled in Philadelphia. In the Quaker city, he rented a building, hired workers to renovate the space, advertised, and assisted by his secretary William Schlumberger, assembled his automata. Amusing and often educational machines, automata had been common in Europe for decades. Baron Wolfgang von Kempelen, a counselor to Austro-Hungarian Empress Maria Theresa, had constructed The Turk back in 1769. Its arrival in the United States created the sensation, and profits, no longer available in Europe. For eleven years, Maelzel and his troupe toured the nation, visiting New York City, Boston, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Richmond, Charleston, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Louisville, and New Orleans.

Everyone marveled at The Turk and wondered how it worked. Was it evidence of a future dominated by machines? Could The Turk think? If so, was this good, natural, moral? Or was The Turk a hoax? Observers hazarded various answers to those questions. Edgar Allan Poe

In late 1837, Maelzel and his troupe made a second trip to Cuba for an extended stay. There, Maelzel suffered a series of misfortunes: attendance dropped and the show lost money, Schlumberger died of yellow fever, and his assistants abandoned him. Alone, broke and depressed, Maelzel borrowed enough money to return to Philadelphia, where he planned to open a new show. He died at sea, however, and his body was cast overboard off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina, on July 21, 1838. His automata and other belongings were auctioned in Philadelphia to pay his creditors.

The Turk's new owner, Dr. John Kearsley Mitchell (father of frightened Silas), lacked Maelzel's panache and showmanship skills. Public interest in the "Automaton Chess Player" waned dramatically, so in 1840 Mitchell donated the machine to Nathan Dunn's "Chinese Museum" at Ninth and George (now Sansom) streets, where it was largely forgotten, and then destroyed by fire on July 5, 1854.

So what was The Turk's secret? Maelzel's famous Automaton Chess Player was, in fact, a clever hoax; Schulmberger operated it from inside the cabinet. He avoided detection by moving forward or backward on a sliding seat when the cabinet doors were opened in proper sequence. The history of American entertainment is filled with similar ploys. P.T. Barnum-who had met Maelzel in 1835 and been advised by the German to make good use of the press-was famous for humbugs like "the man in the moon" and the "FeeJee mermaid."

The Turk, however, did more than amuse people. It prompted some thoughtful Americans to ask profound questions about the relationship between science and religion, and the potential of science to change the world. Mary Shelley also examined these questions in her novel Frankenstein,a book read by many Americans after its American publication in Philadelphia in 1831.

The mystery behind The Turk also fueled the growing fascination with machines. American life and culture were in the process of being revolutionized by steam engines, locomotives, steamboats, and the telegraph. Artificial intelligence seemed like the next step. Within a century, it was a reality. In 1946 scientists working at the University of Pennsylvania developed

Three years later, electrical engineer and mathematician Dr. Claude Shannon built another Turk, the first computer to play chess. In tests reminiscent of Maelzel's exhibitions, engineers and scientists used chess to compare the capabilities of humans and computers. Humans consistently beat their mechanical opponents until 1997, when IBM's Turk, "Deep Blue," defeated international chess master Gary Kasparov in a match that Maelzel, no doubt, would have enjoyed.