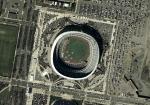

![header=[Marker Text] body=[A multi-purpose stadium opened here in 1971 and served as home to Philadelphia Phillies and Philadelphia Eagles, 1971-2003. The stadium was the site of three World Series in 1980, 1983, and 1993; two Major League Baseball All-Star games in 1976 and 1996; two National Football Conference Championship games in 1981 and 2003; and 17 Army-Navy football games. "The Vet" had a seating capacity of over 65,000; razed in 2004. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-313-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0k6g5-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Veterans Stadium

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

Broad St. and Pattison Ave., Philadelphia

Dedication Date:

September 28, 2005

Behind the Marker

Although officially dubbed Philadelphia Veterans Stadium, the cavernous hulk that rose from a 74-acre patch of marshland across from the Spectrum at the northeast corner of Broad and Pattison was never referred to as anything but The Vet. And nobody particularly liked it.

For fans, the venue certainly wasn't intimate; with seating on seven color-coded levels, ticket-holders along the top perimeter might as well have been sitting in Detroit. For players, especially football players, the rock-hard surface beneath the field's artificial turf was as subtle as a hammer, and contributed to its share of career-shortening injuries. For baseball purists, it was a structural eyesore with cookie-cutter dimensions and a playing field devoid of character.

So, no, nobody much liked The Vet. Among the die-hard football faithful, however, it inspired a begrudged loyalty, and was as much a public showcase for Philadelphia's loud, critical fan base as for the teams they ached to cheer, but enthusiastically booed when the performances they had paid to witness were sub-par.

Compared to the arenas it replaced–the Phillies' Connie Mack Stadium (born as Shibe Park) and the Eagles' Franklin Field–The Vet lacked personality. Architecturally, its fully-enclosed almost circular design was charmless. But then charm and personality were never meant to be its strong suits; function was, and so was access. Like its two closest relatives–Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium–the city-owned Vet was designed to house both football and baseball; supplant parks in inner city neighborhoods that fans, in the wake of the racially volatile 1960s, were uncomfortable visiting; and sit adjacent to major highways for easy access from the suburbs. Picking up on a trend begun with the success of Baltimore's retro-style baseball field, Camden Yards, in the early 1990s, all three of these stadiums gave way to friendlier confines, including Philadelphia's Citizens Bank Park and Lincoln Financial Field and Pittsburgh's PNC Park and Heinz Field, geared specifically to the sports they house.

Shibe Park) and the Eagles' Franklin Field–The Vet lacked personality. Architecturally, its fully-enclosed almost circular design was charmless. But then charm and personality were never meant to be its strong suits; function was, and so was access. Like its two closest relatives–Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium–the city-owned Vet was designed to house both football and baseball; supplant parks in inner city neighborhoods that fans, in the wake of the racially volatile 1960s, were uncomfortable visiting; and sit adjacent to major highways for easy access from the suburbs. Picking up on a trend begun with the success of Baltimore's retro-style baseball field, Camden Yards, in the early 1990s, all three of these stadiums gave way to friendlier confines, including Philadelphia's Citizens Bank Park and Lincoln Financial Field and Pittsburgh's PNC Park and Heinz Field, geared specifically to the sports they house.

Even before it was built, the Vet suffered its share of star-crossed moments. As far back as 1953 members of Philadelphia's City Council locked horns over the idea of a multi-purpose stadium. First they could not agree on where to put it, then they fought over what it should look like, how much it should cost, how to pay for it, and even what to name it. (As the Vietnam War politically split the country, veterans groups heavily lobbied the city, and ultimately prevailed.) With a vision of creating a destination sports complex for the region, ground was finally broken in 1967 on what would balloon into a $50 million enterprise–the most expensive of its time. Between cost overruns and uncooperative weather, the opening was delayed a full year, but opening day, April 10, 1971, was truly memorable.

More than 55,000, the largest ever to gather for a baseball game in Pennsylvania to that time, came out to watch the Phillies defeat the Montreal Expos in a very unbaseball-like 40-degree chill. Future Hall-of-Fame pitcher Jim Bunning notched the victory, and the Phils' future manager, Larry Bowa, recorded the inaugural hit. In a nice link with the past, the old home plate from Connie Mack Stadium was drafted into service, and placed into position on the artificial field.

Overall, the Vet witnessed the most successful teams in Phillies' history. Led by the tireless left arm of pitcher Steve Carleton and the home-run bat and satin glove of third baseman Mike Schmidt, the once-perennial doormats of the National League blossomed into contenders, winning three consecutive division titles in the late 1970s, a pennant and World Series, and two more pennants, in 1983 and 1993. Twice, the All-Star Game came to town.

The Eagles also did well in their new environment, regularly reaching the play-offs behind a trio of strong field-commanders: quarterbacks Ron Jaworski, Randall Cunningham, and Donovan McNabb. Yet, throughout the NFL, the Vet became legend as much for went on in the stands as what happened on the field. Indeed, visiting players likened it to "a hellhole." In a 1989 game against the Dallas Cowboys, rowdy fans tossed snowballs at visiting players, coaches and officials; even then Mayor Ed Rendell got into the act–to his later embarrassment and chagrin–betting a fan that one of his missiles couldn't reach the field. Eight years later, the Eagles became the first team in sports to set up an on-site courtroom to handle the gamut of game-day infractions from public drunkenness, to fist-fights, to harassing visiting rooters. To help maintain decorum, the police department even dispatched officers dressed in opposition jerseys to sit in the Vet's upper 700-level.

Besides the Phillies and Eagles, the Vet, through the 1970s, housed Philadelphia's two professional soccer teams, and the Philadelphia Stars of the short-lived United States Football League. From 1978 to 2002, Temple University used the stadium for football, and rock acts like The Who and Bruce Springsteen filled its seats, as did evangelist Billy Graham's crusade and gatherings of Jehovah's Witnesses. The Vet also hosted the annual Army-Navy game seventeen times. Again, though, it wasn't what happened on the field that always resonated. In 1998, a lower-level support-rail gave way and several Cadets were injured. As was The Vet. Fatally.

Despite the $40 million that Philadelphia began pouring into the facility in the early 1990s to upgrade it with new seats, an electronic scoreboard, and, in a dying last gasp, a new artificial field in 2001, the collapse made it clear that it was time for The Vet to go.

The Eagles played their last game at the Vet in 2002; the Phillies played theirs a year later. Finally, on March 21, 2004, The Vet disappeared in a matter of moments, imploded by dynamite. It is now a parking lot for the two stadiums that replaced it.

For fans, the venue certainly wasn't intimate; with seating on seven color-coded levels, ticket-holders along the top perimeter might as well have been sitting in Detroit. For players, especially football players, the rock-hard surface beneath the field's artificial turf was as subtle as a hammer, and contributed to its share of career-shortening injuries. For baseball purists, it was a structural eyesore with cookie-cutter dimensions and a playing field devoid of character.

So, no, nobody much liked The Vet. Among the die-hard football faithful, however, it inspired a begrudged loyalty, and was as much a public showcase for Philadelphia's loud, critical fan base as for the teams they ached to cheer, but enthusiastically booed when the performances they had paid to witness were sub-par.

Compared to the arenas it replaced–the Phillies' Connie Mack Stadium (born as

Even before it was built, the Vet suffered its share of star-crossed moments. As far back as 1953 members of Philadelphia's City Council locked horns over the idea of a multi-purpose stadium. First they could not agree on where to put it, then they fought over what it should look like, how much it should cost, how to pay for it, and even what to name it. (As the Vietnam War politically split the country, veterans groups heavily lobbied the city, and ultimately prevailed.) With a vision of creating a destination sports complex for the region, ground was finally broken in 1967 on what would balloon into a $50 million enterprise–the most expensive of its time. Between cost overruns and uncooperative weather, the opening was delayed a full year, but opening day, April 10, 1971, was truly memorable.

More than 55,000, the largest ever to gather for a baseball game in Pennsylvania to that time, came out to watch the Phillies defeat the Montreal Expos in a very unbaseball-like 40-degree chill. Future Hall-of-Fame pitcher Jim Bunning notched the victory, and the Phils' future manager, Larry Bowa, recorded the inaugural hit. In a nice link with the past, the old home plate from Connie Mack Stadium was drafted into service, and placed into position on the artificial field.

Overall, the Vet witnessed the most successful teams in Phillies' history. Led by the tireless left arm of pitcher Steve Carleton and the home-run bat and satin glove of third baseman Mike Schmidt, the once-perennial doormats of the National League blossomed into contenders, winning three consecutive division titles in the late 1970s, a pennant and World Series, and two more pennants, in 1983 and 1993. Twice, the All-Star Game came to town.

The Eagles also did well in their new environment, regularly reaching the play-offs behind a trio of strong field-commanders: quarterbacks Ron Jaworski, Randall Cunningham, and Donovan McNabb. Yet, throughout the NFL, the Vet became legend as much for went on in the stands as what happened on the field. Indeed, visiting players likened it to "a hellhole." In a 1989 game against the Dallas Cowboys, rowdy fans tossed snowballs at visiting players, coaches and officials; even then Mayor Ed Rendell got into the act–to his later embarrassment and chagrin–betting a fan that one of his missiles couldn't reach the field. Eight years later, the Eagles became the first team in sports to set up an on-site courtroom to handle the gamut of game-day infractions from public drunkenness, to fist-fights, to harassing visiting rooters. To help maintain decorum, the police department even dispatched officers dressed in opposition jerseys to sit in the Vet's upper 700-level.

Besides the Phillies and Eagles, the Vet, through the 1970s, housed Philadelphia's two professional soccer teams, and the Philadelphia Stars of the short-lived United States Football League. From 1978 to 2002, Temple University used the stadium for football, and rock acts like The Who and Bruce Springsteen filled its seats, as did evangelist Billy Graham's crusade and gatherings of Jehovah's Witnesses. The Vet also hosted the annual Army-Navy game seventeen times. Again, though, it wasn't what happened on the field that always resonated. In 1998, a lower-level support-rail gave way and several Cadets were injured. As was The Vet. Fatally.

Despite the $40 million that Philadelphia began pouring into the facility in the early 1990s to upgrade it with new seats, an electronic scoreboard, and, in a dying last gasp, a new artificial field in 2001, the collapse made it clear that it was time for The Vet to go.

The Eagles played their last game at the Vet in 2002; the Phillies played theirs a year later. Finally, on March 21, 2004, The Vet disappeared in a matter of moments, imploded by dynamite. It is now a parking lot for the two stadiums that replaced it.