![header=[Marker Text] body=[Co-founder of Pittsburgh's Black Horizon Theater and the author of a cycle of ten plays that have been hailed as a unique triumph in American literature. The plays cover each decade of the 20th century and most focus on African American life in the Hill District. Two of the plays, "Fences" and "The Piano Lesson," won Pulitzer prizes for best drama in 1987 and 1990; "Fences" also won Broadway's Tony Award. This site is Wilson's birthplace. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-271-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0k0c1-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

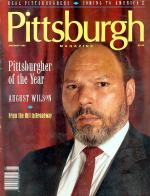

August Wilson

Region:

Pittsburgh Region

County:

Allegheny

Marker Location:

1727 Bedford Ave., Pittsburgh

Dedication Date:

May 30, 2007

Behind the Marker

If August Wilson's observation today seems self-evident, it was his own remarkable achievement that so contributed to giving it voice. The playwright made it his mission to root around that mythology, culture, and history, to honor and explore the black experience in America's twentieth century, to extol the nobility of its struggle, and to expose the ugly residues of racism. By every theatrical measure - awards, reviews, and the more than 2,000 productions of his plays from Broadway and Off Broadway to repertory and amateur theaters around the country - he succeeded spectacularly.

"No one except perhaps Eugene O'Neill and Tennessee Williams has aimed so high and achieved do much in the American theater," observed John Lahr, the influential drama critic of The New Yorker. Through ten powerful dramas, one for each decade of the black experience of the twentieth century, Wilson chronicled a rich and unique world that had never before received such a comprehensive and vibrant treatment on the stage. "I am taking each decade," Wilson once told an interviewer, "and looking at one of the most important questions that blacks confronted in that decade and writing a play about it. Put them together and you have a history."

The child of a mixed marriage, August Wilson was born Frederick August Kittell in Pittsburgh on April 27, 1945, and grew up in "The Hill," the city's famed African-American section, until his mother remarried when August was in his teens. His biological father was white, a German immigrant who worked as a baker, drank too much, and largely absented himself from his six children's lives before abandoning the family altogether. His mother, a cleaning woman, was the family's rock; when Wilson decided to become a writer, he legally replaced "Kittell" with her maiden name. It was, he would say, his sign of respect for the dignity and pride she filled him with.

Spurred by the belief that better opportunity awaited in a white community, the family moved to the suburbs after Wilson's mother remarried, but opportunity never knocked. The only black student in a Roman Catholic high school, he remembered parrying racial taunts from classmates every day, and when, at fifteen, a teacher accused him of plagiarizing a paper, he left school altogether. That's when, he liked to say, his real education began.

Thirsty for knowledge - and surroundings he felt he fit into - Wilson returned to The Hill, working menial jobs to support himself, before disappearing for hours at a time into the public library. There, he soaked himself in the words and stories of Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and other black writers. Wilson also frequented the local cafes and shops, and hung out on stoops and street corners. Watching and listening, he absorbed the cadences, conversations, concerns, and characters he would later populate his plays with. He already knew he wanted to be a writer, and with the $20 he had charged one of his sisters for ghostwriting a college term paper, he bought his first typewriter. By the age of twenty, he was sending his poetry to literary journals.

Stirred by the Black Power movement, Wilson - and his work - became more militant and political. In 1968, along with his friend Rob Penny, a teacher and playwright, he co-founded Black Horizon, an activist theater company intent on raising the consciousness of Pittsburgh's black community. Though he had no experience in the theater, Wilson gamely tried his hand at acting and directing, and experimented with playwrighting.

In 1978, Wilson moved to St. Paul to work at the Science Museum of Minnesota, where one of his responsibilities was to turn American folk tales into children's plays. Here, Wilson returned in his imagination to The Hill, and to the voices and stories that kept bubbling up in his memory. In 1979, he wrote Jitney. Set in the 1970s, it intertwined the story of a son's return to The Hill from prison with his father's struggle to keep his cab company running. His next effort, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, which he set in a Chicago recording studio in the 1920s, was accepted by the National Playwrights Conference. Wilson then began what would become a long and powerful collaboration with the conference's director, Lloyd Richards, the dean of the Yale School of Drama.

Richards directed Ma Rainey, the only play in the cycle that doesn't take place on The Hill, at Yale in 1984. The play then moved on to Philadelphia and then to Broadway, where reviewers lauded both the play - the New York Times called it "a searing account of what white racism does to its victims" - and the stunning talent of its writer; the New York Drama Critics Circle honored it as the year's best play. Wilson followed in 1985 with Fences, about a bitter former Negro League ball-player. Set in the 1950s, it reached Broadway in 1987 and then won several Tony Awards and the Pulitzer Prize in drama. (Wilson would win a second Pulitzer in 1990, for The Piano Lesson, his ode to the 1930s, in which the piano itself becomes a bittersweet symbol of the past for the family that owns it.)

Though Wilson hadn't begun with the idea of chronicling the black struggle in American decade by decade, his first three plays established the framework, and the seven that followed, though they skipped around in time, completed the structure. Each was its own unique enterprise, but they tied to one another in many ways: by Wilson's insistence that blacks in America must acknowledge and honor the pain of their past; by the themes of prejudice, struggle, dignity, family, and fulfillment that worked through them; by Wilson's powerful use of language - his dialogue, wrote one critic, "married the complexity of jazz to the emotional power of the blues"; and by the individual characters that would echo and reverberate through the cycle. Something else also ties them together: possibility. "In all the plays," Wilson insisted, "the characters remain pointed toward the future, their pockets lined with fresh hope and an abiding faith in their own abilities and their own heroics."

Wilson believed so strongly in the power of theater, that, with the exception of a television version of "The Piano Lesson," which he retained almost complete control over, he refused to adapt his work for Hollywood. Still, he had no trouble attracting the best black actors of his time - among them James Earl Jones, Charles S. Dutton, Angela Bassett, Roscoe Lee Brown, Leslie Uggams, and Laurence Fishburne - to breath for his characters on stage.

By the mid-1990s, Wilson relocated to Seattle, where he lived until his death, at age sixty, on October 2, 2005, from liver cancer. Shortly after his death, he received an honor from the theater community far rarer than any Tony or Pulitzer: a Broadway stage was rechristened in his name.

"I simply believe that blacks have culture, and that we have our own mythology, our own history, our own social organization, our own creative motif."

-August Wilson

If August Wilson's observation today seems self-evident, it was his own remarkable achievement that so contributed to giving it voice. The playwright made it his mission to root around that mythology, culture, and history, to honor and explore the black experience in America's twentieth century, to extol the nobility of its struggle, and to expose the ugly residues of racism. By every theatrical measure - awards, reviews, and the more than 2,000 productions of his plays from Broadway and Off Broadway to repertory and amateur theaters around the country - he succeeded spectacularly.

"No one except perhaps Eugene O'Neill and Tennessee Williams has aimed so high and achieved do much in the American theater," observed John Lahr, the influential drama critic of The New Yorker. Through ten powerful dramas, one for each decade of the black experience of the twentieth century, Wilson chronicled a rich and unique world that had never before received such a comprehensive and vibrant treatment on the stage. "I am taking each decade," Wilson once told an interviewer, "and looking at one of the most important questions that blacks confronted in that decade and writing a play about it. Put them together and you have a history."

The child of a mixed marriage, August Wilson was born Frederick August Kittell in Pittsburgh on April 27, 1945, and grew up in "The Hill," the city's famed African-American section, until his mother remarried when August was in his teens. His biological father was white, a German immigrant who worked as a baker, drank too much, and largely absented himself from his six children's lives before abandoning the family altogether. His mother, a cleaning woman, was the family's rock; when Wilson decided to become a writer, he legally replaced "Kittell" with her maiden name. It was, he would say, his sign of respect for the dignity and pride she filled him with.

Spurred by the belief that better opportunity awaited in a white community, the family moved to the suburbs after Wilson's mother remarried, but opportunity never knocked. The only black student in a Roman Catholic high school, he remembered parrying racial taunts from classmates every day, and when, at fifteen, a teacher accused him of plagiarizing a paper, he left school altogether. That's when, he liked to say, his real education began.

Thirsty for knowledge - and surroundings he felt he fit into - Wilson returned to The Hill, working menial jobs to support himself, before disappearing for hours at a time into the public library. There, he soaked himself in the words and stories of Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and other black writers. Wilson also frequented the local cafes and shops, and hung out on stoops and street corners. Watching and listening, he absorbed the cadences, conversations, concerns, and characters he would later populate his plays with. He already knew he wanted to be a writer, and with the $20 he had charged one of his sisters for ghostwriting a college term paper, he bought his first typewriter. By the age of twenty, he was sending his poetry to literary journals.

Stirred by the Black Power movement, Wilson - and his work - became more militant and political. In 1968, along with his friend Rob Penny, a teacher and playwright, he co-founded Black Horizon, an activist theater company intent on raising the consciousness of Pittsburgh's black community. Though he had no experience in the theater, Wilson gamely tried his hand at acting and directing, and experimented with playwrighting.

In 1978, Wilson moved to St. Paul to work at the Science Museum of Minnesota, where one of his responsibilities was to turn American folk tales into children's plays. Here, Wilson returned in his imagination to The Hill, and to the voices and stories that kept bubbling up in his memory. In 1979, he wrote Jitney. Set in the 1970s, it intertwined the story of a son's return to The Hill from prison with his father's struggle to keep his cab company running. His next effort, Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, which he set in a Chicago recording studio in the 1920s, was accepted by the National Playwrights Conference. Wilson then began what would become a long and powerful collaboration with the conference's director, Lloyd Richards, the dean of the Yale School of Drama.

Richards directed Ma Rainey, the only play in the cycle that doesn't take place on The Hill, at Yale in 1984. The play then moved on to Philadelphia and then to Broadway, where reviewers lauded both the play - the New York Times called it "a searing account of what white racism does to its victims" - and the stunning talent of its writer; the New York Drama Critics Circle honored it as the year's best play. Wilson followed in 1985 with Fences, about a bitter former Negro League ball-player. Set in the 1950s, it reached Broadway in 1987 and then won several Tony Awards and the Pulitzer Prize in drama. (Wilson would win a second Pulitzer in 1990, for The Piano Lesson, his ode to the 1930s, in which the piano itself becomes a bittersweet symbol of the past for the family that owns it.)

Though Wilson hadn't begun with the idea of chronicling the black struggle in American decade by decade, his first three plays established the framework, and the seven that followed, though they skipped around in time, completed the structure. Each was its own unique enterprise, but they tied to one another in many ways: by Wilson's insistence that blacks in America must acknowledge and honor the pain of their past; by the themes of prejudice, struggle, dignity, family, and fulfillment that worked through them; by Wilson's powerful use of language - his dialogue, wrote one critic, "married the complexity of jazz to the emotional power of the blues"; and by the individual characters that would echo and reverberate through the cycle. Something else also ties them together: possibility. "In all the plays," Wilson insisted, "the characters remain pointed toward the future, their pockets lined with fresh hope and an abiding faith in their own abilities and their own heroics."

Wilson believed so strongly in the power of theater, that, with the exception of a television version of "The Piano Lesson," which he retained almost complete control over, he refused to adapt his work for Hollywood. Still, he had no trouble attracting the best black actors of his time - among them James Earl Jones, Charles S. Dutton, Angela Bassett, Roscoe Lee Brown, Leslie Uggams, and Laurence Fishburne - to breath for his characters on stage.

By the mid-1990s, Wilson relocated to Seattle, where he lived until his death, at age sixty, on October 2, 2005, from liver cancer. Shortly after his death, he received an honor from the theater community far rarer than any Tony or Pulitzer: a Broadway stage was rechristened in his name.

Beyond the Marker