![header=[Marker Text] body=[Religious, cultural, and industrial center. Founded 1741 by Moravians, who excelled as missionaries and musicians. Place of refuge during Indian wars. Lehigh Canal, opened 1829, brought industrialization. Home of Bethlehem Steel.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-239-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h6s9-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Bethlehem

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Northampton

Marker Location:

PA 412 entering city from S

Dedication Date:

July 26, 1948

Behind the Marker

Bethlehem has a distinctive colonial history as a pioneering Moravian community, and a secure place in northeastern Pennsylvania's anthracite industry, but its celebrity as "the arsenal of America" and its vital importance for the American steel industry centers on the saga of Bethlehem Steel. For more than a century Bethlehem was a microcosm for the nation's steel industry.

Beginning in the 1870s, Bethlehem's steel was made into rails, battleships, factories, skyscrapers, and more. The company amassed an impressive track record of technical innovation, and owing to the leadership of Charles Schwab it grew into the nation's second largest steel producer in the 1920s.

Charles Schwab it grew into the nation's second largest steel producer in the 1920s.

Unfortunately, Bethlehem also mirrored steel's decline. From the 1970s the company struggled with outmoded production technology, high labor costs, and stiff international competition. Steelmaking in Bethlehem, after nearly a century and a quarter, ended on November 18, 1995.

Bethlehem Iron, founded in 1861, became a steel company when it built the nation's tenth Bessemer steel rail mill a dozen years later. John Fritz, inventor of the industry-standard three-high rail mill while he was at

John Fritz, inventor of the industry-standard three-high rail mill while he was at  Cambria, helped perfect the making of Bessemer steel rails at Bethlehem but he recognized that the company's rail mill could not compete economically against

Cambria, helped perfect the making of Bessemer steel rails at Bethlehem but he recognized that the company's rail mill could not compete economically against  Andrew Carnegie's cost-busting Pittsburgh complex. After the death of railroad man

Andrew Carnegie's cost-busting Pittsburgh complex. After the death of railroad man  Asa Packer, who had tightly controlled the company for years, and its subsequent purchase by entrepreneur Joseph Wharton, Fritz got his chance in 1885. He built Bethlehem into the "arsenal of America" by importing special heavy-forging equipment from England and France and entering the lucrative market for battleship armor.

Asa Packer, who had tightly controlled the company for years, and its subsequent purchase by entrepreneur Joseph Wharton, Fritz got his chance in 1885. He built Bethlehem into the "arsenal of America" by importing special heavy-forging equipment from England and France and entering the lucrative market for battleship armor.

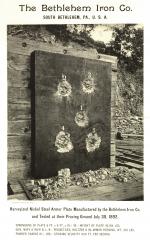

Bethlehem commanded tonnage prices for its armor roughly ten times those for steel rails. The company also began making oversize gun barrels for battleships and coastal fortifications. Frederick Taylor, the controversial "scientific management" guru, invented his landmark high-speed tool steel in Bethlehem's heavy gun shop. The company's renowned "Beth Forge" division grew directly from these roots. It hammered 70 tons of steel into the 45-foot-long axle for George Ferris's revolving wheel installed at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. The Panama Canal's 110-foot-high lock gates also came from Bethlehem.

Frederick Taylor, the controversial "scientific management" guru, invented his landmark high-speed tool steel in Bethlehem's heavy gun shop. The company's renowned "Beth Forge" division grew directly from these roots. It hammered 70 tons of steel into the 45-foot-long axle for George Ferris's revolving wheel installed at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. The Panama Canal's 110-foot-high lock gates also came from Bethlehem.

From the 1880s through the 1920s, Bethlehem took up and perfected a string of challenging technical innovations. It was one of a select few firms in the world to successfully make special hardened armor used in the great powers" World War I battleships. This armor was hard as glass on the outside, yet had a flexible inside to absorb the impact of incoming shells. The company saw an opportunity in building steel bridges and skyscrapers, and it built an open-hearth steelmaking plant in 1907 for this new market.

Unlike the fiery Bessemer converter, which blasted air through molten iron to make steel in as little as ten minutes, the open hearth furnace generated extremely high temperatures to make a "heat" of steel in a comparatively unhurried eight to twenty-four hours. Since the metal could be repeatedly tested while in the furnace, open hearth steel was of higher quality and more uniform. Open hearth steel fed a new $4 million rolling mill that Bethlehem built in 1908. This patented mill rolled mammoth structural beams up to 36 inches in height. With flanges much wider than in standard "I" beams, they were known as "H" beams, and again Bethlehem commanded premium prices for them. It is Bethlehem's steel in New York's Chrysler Building and George Washington Bridge, Philadelphia's Benjamin Franklin Bridge, and San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge.

In September 1939 Bethlehem chairman Eugene Grace was out on the company's golf course when word came that World War II had just begun. "Gentlemen, we are going to make a lot of money," he reportedly told his fellow golfer-executives. In the war effort Bethlehem fortified its reputation as the arsenal of America, producing around one-fourth of the wartime battleship armor, heavy gun barrels, and ships for the Navy, in addition to nearly three-quarters of the airplane engine cylinders. In retrospect, though, we can see that the postwar 1950s was a crucial one for the steel industry and that Bethlehem under Grace made several tragic mistakes with disastrous consequences.

Eugene Grace was out on the company's golf course when word came that World War II had just begun. "Gentlemen, we are going to make a lot of money," he reportedly told his fellow golfer-executives. In the war effort Bethlehem fortified its reputation as the arsenal of America, producing around one-fourth of the wartime battleship armor, heavy gun barrels, and ships for the Navy, in addition to nearly three-quarters of the airplane engine cylinders. In retrospect, though, we can see that the postwar 1950s was a crucial one for the steel industry and that Bethlehem under Grace made several tragic mistakes with disastrous consequences.

Bethlehem faced three pressing challenges in the 1950s. To compete effectively, Bethlehem needed to reverse its dismal labor-management relations. Grace, as Bethlehem's president since 1913 and chairman since 1945, had set the company's confrontational labor policy. Having supported the anti-labor "open shop" campaign of the 1920s, Grace walked out on a key conference in 1933 with the U.S. Labor Secretary Frances Perkins when a union leader walked in, explaining later "we have an almost sacred policy that we will never recognize organized labor."

Frances Perkins when a union leader walked in, explaining later "we have an almost sacred policy that we will never recognize organized labor."

In 1941, six years after the landmark Wagner Act had compelled all companies to recognize the rights of U.S. workers to form independent unions, Bethlehem provoked a second "Little Steel" strike. In the 1950s the company did little to improve this climate, backing the 1959 strike, which lasted 116 days and led many U.S. consumers of steel to seek more reliable foreign suppliers of steel.

Bethlehem's second challenge was managing its great affluence. Instead of following a Carnegie-Schwab policy of aggressive innovation, Bethlehem spent a mountain of money on executive perks. In the mid-1950s, its executives held seven of the nation's ten highest-paid jobs. Company dining rooms featured extravagant meals (with leftovers taken home for private weekend entertaining), and its executives lived like princes on Prospect Avenue, known as "Bonus Hill," often with domestic help from company-paid grounds staff. The company's police force was larger than the city's.

Bethlehem's confrontational labor policies and executives' greed made it doubly difficult to take up the third challenge: new production technology. Beginning in the 1950s, Japan and Germany rebuilt their war-damaged steel plants with new production technologies, including basic-oxygen furnaces and continuous casting. Both of these innovations made high quality steel at substantially lower cost than in open-hearth furnaces.

Bethlehem spent lavishly on a new research lab in the 1960s, but few innovations came from it. Bethlehem's managers and workers, even its townspeople, did not really understand the serious trouble facing the company - and the industry - until it was too late. Before investing a dime in continuous casters, the company spent $35 million on a 21-story office complex. Among the architectural features of Martin Towers is its distinctive "cruciform" shape, designed to permit innumerable vice presidents to have offices with corner windows.

During the 1980s, when America lost half of its steel jobs in just ten years, union members clung to elaborate work rules that specified who could do which jobs. Contract settlements thirty years earlier had stipulated that the prevailing work rules could be changed only when new processes were installed, effectively locking many steel plants, including Bethlehem's, into the past.

An early sign of the company's deep troubles was "Black Friday," September 30, 1977, when the company laid off 10,000 employees. Across the grim 1980s the company slashed jobs and made sizable investment only to its mills at Burns Harbor, Indiana, and Sparrows Point, Maryland. A dire sign came in 1983 when, for the first time, more people collected pensions from Bethlehem than paychecks. When the company finally filed for bankruptcy in October 2001, only 13,000 paid employees remained compared to 95,000 retirees.

Beginning in the 1870s, Bethlehem's steel was made into rails, battleships, factories, skyscrapers, and more. The company amassed an impressive track record of technical innovation, and owing to the leadership of

Unfortunately, Bethlehem also mirrored steel's decline. From the 1970s the company struggled with outmoded production technology, high labor costs, and stiff international competition. Steelmaking in Bethlehem, after nearly a century and a quarter, ended on November 18, 1995.

Bethlehem Iron, founded in 1861, became a steel company when it built the nation's tenth Bessemer steel rail mill a dozen years later.

Bethlehem commanded tonnage prices for its armor roughly ten times those for steel rails. The company also began making oversize gun barrels for battleships and coastal fortifications.

From the 1880s through the 1920s, Bethlehem took up and perfected a string of challenging technical innovations. It was one of a select few firms in the world to successfully make special hardened armor used in the great powers" World War I battleships. This armor was hard as glass on the outside, yet had a flexible inside to absorb the impact of incoming shells. The company saw an opportunity in building steel bridges and skyscrapers, and it built an open-hearth steelmaking plant in 1907 for this new market.

Unlike the fiery Bessemer converter, which blasted air through molten iron to make steel in as little as ten minutes, the open hearth furnace generated extremely high temperatures to make a "heat" of steel in a comparatively unhurried eight to twenty-four hours. Since the metal could be repeatedly tested while in the furnace, open hearth steel was of higher quality and more uniform. Open hearth steel fed a new $4 million rolling mill that Bethlehem built in 1908. This patented mill rolled mammoth structural beams up to 36 inches in height. With flanges much wider than in standard "I" beams, they were known as "H" beams, and again Bethlehem commanded premium prices for them. It is Bethlehem's steel in New York's Chrysler Building and George Washington Bridge, Philadelphia's Benjamin Franklin Bridge, and San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge.

In September 1939 Bethlehem chairman

Bethlehem faced three pressing challenges in the 1950s. To compete effectively, Bethlehem needed to reverse its dismal labor-management relations. Grace, as Bethlehem's president since 1913 and chairman since 1945, had set the company's confrontational labor policy. Having supported the anti-labor "open shop" campaign of the 1920s, Grace walked out on a key conference in 1933 with the U.S. Labor Secretary

In 1941, six years after the landmark Wagner Act had compelled all companies to recognize the rights of U.S. workers to form independent unions, Bethlehem provoked a second "Little Steel" strike. In the 1950s the company did little to improve this climate, backing the 1959 strike, which lasted 116 days and led many U.S. consumers of steel to seek more reliable foreign suppliers of steel.

Bethlehem's second challenge was managing its great affluence. Instead of following a Carnegie-Schwab policy of aggressive innovation, Bethlehem spent a mountain of money on executive perks. In the mid-1950s, its executives held seven of the nation's ten highest-paid jobs. Company dining rooms featured extravagant meals (with leftovers taken home for private weekend entertaining), and its executives lived like princes on Prospect Avenue, known as "Bonus Hill," often with domestic help from company-paid grounds staff. The company's police force was larger than the city's.

Bethlehem's confrontational labor policies and executives' greed made it doubly difficult to take up the third challenge: new production technology. Beginning in the 1950s, Japan and Germany rebuilt their war-damaged steel plants with new production technologies, including basic-oxygen furnaces and continuous casting. Both of these innovations made high quality steel at substantially lower cost than in open-hearth furnaces.

Bethlehem spent lavishly on a new research lab in the 1960s, but few innovations came from it. Bethlehem's managers and workers, even its townspeople, did not really understand the serious trouble facing the company - and the industry - until it was too late. Before investing a dime in continuous casters, the company spent $35 million on a 21-story office complex. Among the architectural features of Martin Towers is its distinctive "cruciform" shape, designed to permit innumerable vice presidents to have offices with corner windows.

During the 1980s, when America lost half of its steel jobs in just ten years, union members clung to elaborate work rules that specified who could do which jobs. Contract settlements thirty years earlier had stipulated that the prevailing work rules could be changed only when new processes were installed, effectively locking many steel plants, including Bethlehem's, into the past.

An early sign of the company's deep troubles was "Black Friday," September 30, 1977, when the company laid off 10,000 employees. Across the grim 1980s the company slashed jobs and made sizable investment only to its mills at Burns Harbor, Indiana, and Sparrows Point, Maryland. A dire sign came in 1983 when, for the first time, more people collected pensions from Bethlehem than paychecks. When the company finally filed for bankruptcy in October 2001, only 13,000 paid employees remained compared to 95,000 retirees.