![header=[Marker Text] body=[The great painter of Indian portraits was born here July 26, 1796, of Connecticut ancestry. Until 1823 he practiced law here and nearby. He began painting Indian pictures six years later. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-229-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h5d9-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

George Catlin [Indians]

Region:

Poconos / Endless Mountains

County:

Luzerne

Marker Location:

River and South Sts., Wilkes-Barre

Dedication Date:

October 13, 1947

Behind the Marker

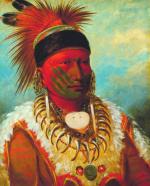

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, to Polly Sutton and lawyer Putnam Catlin, "who entered that beautiful and famed valley soon after the close of the Revolutionary War," George Catlin "whiled away" the early part of his life "with books reluctantly held in one hand, and a rifle or fishing-pole firmly and affectionately grasped in the other." At his father's request he studied law at the Litchfield Academy in Connecticut, his parents' home state, and briefly practiced, before quitting in disgust at the age of twenty-five. He then moved to Philadelphia, where, "without teacher or adviser," he won recognition as an exceptionally skilful painter.

In 1824 the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts elected him a member on the strength of his portraits (mostly miniatures). Three years later he moved to New York, became a member of the National Academy of Art and Design, married Clara Gregory of Albany, and painted more portraits, including the one of Governor DeWitt Clinton that may be viewed in New York's City Hall. Catlin, however, was still dissatisfied, for, as he later wrote, "my mind was continually reaching for some branch of enterprise of the art, on which to devote

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts elected him a member on the strength of his portraits (mostly miniatures). Three years later he moved to New York, became a member of the National Academy of Art and Design, married Clara Gregory of Albany, and painted more portraits, including the one of Governor DeWitt Clinton that may be viewed in New York's City Hall. Catlin, however, was still dissatisfied, for, as he later wrote, "my mind was continually reaching for some branch of enterprise of the art, on which to devote  a whole life-time of enthusiasm."

a whole life-time of enthusiasm."

When a contingent of Indians visited Philadelphia, Catlin found his calling. The Indian diplomats he saw represented "man, in the simplicity and loftiness of his nature, unrestrained and unfettered by the disguises of art." Catlin decided to dedicate his life's work to capturing this natural beauty on canvas, so that "the history and customs of such a people" could be preserved forever.

In 1832, ignoring "those whose anxieties were ready to fabricate every difficulty and danger that could be imagined," Catlin set out for his first journey into the "vast and pathless wilds which are familiarly denominated the great 'Far West.' Time was of the essence, because he was convinced that the Indians of the American West were already "rapidly passing away from the face of the earth," the victims of diseases and alcohol introduced to them by white fur traders.

Over the next nine years, Catlin traveled 1,800 miles up the Missouri River, visited the southern plains and Great Lakes region, and painted more than 300 portraits and 200 scenes of everyday Indian life. His images of the Mandan people, who became extinct from smallpox shortly after his portraits, alone would give value to his life's work. At the conclusion of his travels, he published his invaluable Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians in 1841, still in print, in which he sympathetically, sometimes eloquently, and in great detail recorded the life of the Indians as a worthy counterpart to his bountiful and beautiful illustrations.

Catlin made great claims to the truthfulness of his visual and written descriptions of the Plains Indians, but some of his contemporaries accused him of exaggerations and falsifications, such as when he depicted Mandans living in Sioux teepees. His critics claimed that constant self-promotion often distracted attention away from such inaccuracies in his work.

In his travels out west, Catlin followed in the footsteps of other Pennsylvanians who helped shape the nation's image of Native Americans. Like the German colonial painter Gustavus Hesselius, who painted the Delaware Indians Tishcohan and Lapowinsa, his works conveyed the nobility of Native Americans and their culture. Ironically, just as the Penn proprietors ordered the Hesselius portraits at about the time the infamous "Walking Purchase" of 1737 was dispossessing the Delawares of much of their land, Catlin's works also captured a way of life just before it was overrun by white western expansion.

Other Pennsylvania images generated during the frontier wars of the late eighteenth century, depicted Indians as cannibals and barbarians rather than noble savages. One of several prints - one of the first political cartoons in British North America - defended the Paxton Boys' 1763 massacre of peaceful, Christianized Conestoga Indians by showing an Indian riding to meet Benjamin Franklin on the back of a scalped frontier settler. During the American Revolution, another cartoon showed King George III joining Indians and an Anglican bishop feasting on the bodies of American frontiersmen.

While Catlin made his career and reputation on painting Indians of the trans-Mississippian West, his work also reflected his roots in Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley, which Iroquois and Delaware Indians had called home before their forced dispossession by whites in the 1760s. Catlin completed 22 major portraits of Iroquois, Delaware, or Mahican Indians from the Pennsylvania - New York area, as well as six major landscapes depicting Iroquois country in upstate New York or western Pennsylvania. The most famous of these works are his portraits of the Seneca orator and chief Red Jacket, perhaps the most famous Iroquois of his day, but they also include historical paintings of the seventeenth-century French exploration of Lake Erie and Niagara Falls.

Despite his lavishly illustrated 1841 book and numerous showings at private galleries, Catlin failed to obtain congressional support for his life's dream: a gallery containing his complete drawings along with other artwork and artifacts pertaining to Native Americans. He hoped it would be located in Washington, D.C. Unappreciated in the United States, Catlin traveled to England and France in the 1840s, where he struggled to keep afloat by exhibiting and selling paintings and publishing Notes of Eight Years' Travels and Residence in Europe, with His North American Indian Collection (1848).

Financial setbacks landed him in debtors' prison in London, and only the purchase of all his original paintings - except some he hid-by Philadelphia industrialist Joseph Harrison freed him from his creditors' demands. Residing in England in the 1850s and 1860s, he took three trips to South America, published illustrated children's books of his travels, wrote a history of the Mandans, authored a self-help book, and postulated the theory that the Western Hemisphere took shape through a great geological catastrophe. In the 1860s, he also produced a set of 600 "cartoons" based on his original drawings.

Catlin returned to the United States in 1871, showed his cartoons in New York and at the Smithsonian, and petitioned Congress once more, this time to purchase his original works from their owners and finally establish his dreamed of Indian gallery. Seven years after Catlin's death in 1872, Mrs. Joseph Harrison donated her husband's collection of Catlin's work to the Smithsonian, where combined with Catlin's own donation, they comprised the Indian gallery of which Catlin had dreamed. The National Gallery of Art assembled the cartoon collection. Today, it is housed in the National Museum of the American Indian. Like the Indians he loved and whose life he shared for almost a decade, Catlin "nurtured . . . a burning sense of injury and injustice" thanks to what he sarcastically termed "the glorious influences of refined and moral cultivation."

In 1824 the

When a contingent of Indians visited Philadelphia, Catlin found his calling. The Indian diplomats he saw represented "man, in the simplicity and loftiness of his nature, unrestrained and unfettered by the disguises of art." Catlin decided to dedicate his life's work to capturing this natural beauty on canvas, so that "the history and customs of such a people" could be preserved forever.

In 1832, ignoring "those whose anxieties were ready to fabricate every difficulty and danger that could be imagined," Catlin set out for his first journey into the "vast and pathless wilds which are familiarly denominated the great 'Far West.' Time was of the essence, because he was convinced that the Indians of the American West were already "rapidly passing away from the face of the earth," the victims of diseases and alcohol introduced to them by white fur traders.

Over the next nine years, Catlin traveled 1,800 miles up the Missouri River, visited the southern plains and Great Lakes region, and painted more than 300 portraits and 200 scenes of everyday Indian life. His images of the Mandan people, who became extinct from smallpox shortly after his portraits, alone would give value to his life's work. At the conclusion of his travels, he published his invaluable Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians in 1841, still in print, in which he sympathetically, sometimes eloquently, and in great detail recorded the life of the Indians as a worthy counterpart to his bountiful and beautiful illustrations.

Catlin made great claims to the truthfulness of his visual and written descriptions of the Plains Indians, but some of his contemporaries accused him of exaggerations and falsifications, such as when he depicted Mandans living in Sioux teepees. His critics claimed that constant self-promotion often distracted attention away from such inaccuracies in his work.

In his travels out west, Catlin followed in the footsteps of other Pennsylvanians who helped shape the nation's image of Native Americans. Like the German colonial painter Gustavus Hesselius, who painted the Delaware Indians Tishcohan and Lapowinsa, his works conveyed the nobility of Native Americans and their culture. Ironically, just as the Penn proprietors ordered the Hesselius portraits at about the time the infamous "Walking Purchase" of 1737 was dispossessing the Delawares of much of their land, Catlin's works also captured a way of life just before it was overrun by white western expansion.

Other Pennsylvania images generated during the frontier wars of the late eighteenth century, depicted Indians as cannibals and barbarians rather than noble savages. One of several prints - one of the first political cartoons in British North America - defended the Paxton Boys' 1763 massacre of peaceful, Christianized Conestoga Indians by showing an Indian riding to meet Benjamin Franklin on the back of a scalped frontier settler. During the American Revolution, another cartoon showed King George III joining Indians and an Anglican bishop feasting on the bodies of American frontiersmen.

While Catlin made his career and reputation on painting Indians of the trans-Mississippian West, his work also reflected his roots in Pennsylvania's Wyoming Valley, which Iroquois and Delaware Indians had called home before their forced dispossession by whites in the 1760s. Catlin completed 22 major portraits of Iroquois, Delaware, or Mahican Indians from the Pennsylvania - New York area, as well as six major landscapes depicting Iroquois country in upstate New York or western Pennsylvania. The most famous of these works are his portraits of the Seneca orator and chief Red Jacket, perhaps the most famous Iroquois of his day, but they also include historical paintings of the seventeenth-century French exploration of Lake Erie and Niagara Falls.

Despite his lavishly illustrated 1841 book and numerous showings at private galleries, Catlin failed to obtain congressional support for his life's dream: a gallery containing his complete drawings along with other artwork and artifacts pertaining to Native Americans. He hoped it would be located in Washington, D.C. Unappreciated in the United States, Catlin traveled to England and France in the 1840s, where he struggled to keep afloat by exhibiting and selling paintings and publishing Notes of Eight Years' Travels and Residence in Europe, with His North American Indian Collection (1848).

Financial setbacks landed him in debtors' prison in London, and only the purchase of all his original paintings - except some he hid-by Philadelphia industrialist Joseph Harrison freed him from his creditors' demands. Residing in England in the 1850s and 1860s, he took three trips to South America, published illustrated children's books of his travels, wrote a history of the Mandans, authored a self-help book, and postulated the theory that the Western Hemisphere took shape through a great geological catastrophe. In the 1860s, he also produced a set of 600 "cartoons" based on his original drawings.

Catlin returned to the United States in 1871, showed his cartoons in New York and at the Smithsonian, and petitioned Congress once more, this time to purchase his original works from their owners and finally establish his dreamed of Indian gallery. Seven years after Catlin's death in 1872, Mrs. Joseph Harrison donated her husband's collection of Catlin's work to the Smithsonian, where combined with Catlin's own donation, they comprised the Indian gallery of which Catlin had dreamed. The National Gallery of Art assembled the cartoon collection. Today, it is housed in the National Museum of the American Indian. Like the Indians he loved and whose life he shared for almost a decade, Catlin "nurtured . . . a burning sense of injury and injustice" thanks to what he sarcastically termed "the glorious influences of refined and moral cultivation."