![header=[Marker Text] body=[The major expedition of the Revolution aimed at the Indian-Tory Alliance in New York, was organized at Easton under Gen. John Sullivan. Over a month's preparations preceded the first day's march, begun near here June 18, 1779.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-224-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0h5d4-a_450.jpg)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Sullivan Campaign [Indians]

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Northampton

Marker Location:

Knox Ave. (SR 2025, former PA 115) just N of Easton

Dedication Date:

August 5, 1947

Behind the Marker

Each Indian village the Continental soldiers came to was deserted, its inhabitants having fled westward in advance of the army. Nevertheless, the soldiers were impressed by what they saw: well-built homes, endless fields of corn (some of the stalks sixteen feet tall), orchards with peach, cherry, and apple trees, and bountiful crops of melons, pumpkins, beans, and squash. The soldiers burned or cut down all that they could, leaving nothing for the Indians to come home to.

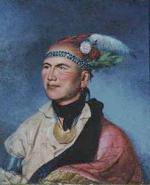

Years later, the Iroquois chief Cornplanter remembered the campaign in a speech to President George Washington: "When your army entered the country of the Six Nations, we called you Town Destroyer: and to this day when that name is heard our women look behind them and turn pale, and our children cling close to the necks of their mothers."

The Sullivan Campaign had its roots in the chronic clashes and resentments between Indians and colonists caused by the Connecticut Settlement of the northern Susquehanna Valley. Those tensions exploded in late 1778 in the crushing defeat of New England militiamen at the

Connecticut Settlement of the northern Susquehanna Valley. Those tensions exploded in late 1778 in the crushing defeat of New England militiamen at the  Battle of Wyoming. Political pressure mounted to do something in retaliation. In late 1778, General George Washington decided to mount a punitive expedition against the Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga, western Iroquois nations that had allied with the British and were supplied by Fort Niagara. Washington then chose General John Sullivan of New Hampshire to lead the expedition.

Battle of Wyoming. Political pressure mounted to do something in retaliation. In late 1778, General George Washington decided to mount a punitive expedition against the Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga, western Iroquois nations that had allied with the British and were supplied by Fort Niagara. Washington then chose General John Sullivan of New Hampshire to lead the expedition.

Sullivan assembled 2,500 men at Easton, planning to march northwest through Wyoming into Iroquoia during the early spring of 1779. There he would meet and cooperate with two other wings of the expedition. General James Clinton's forces were to advance from the Mohawk Valley southwest to meet Sullivan near Tioga, and Pennsylvania Colonel Daniel Brodhead's smaller force was to travel up the Allegheny River from Fort Pitt to meet the main body of troops in the Genesee country west of the Finger Lakes. Collectively, these three forces totaled approximately 5,000 men and reflected Washington's fondness for complex, multi-pronged strategic operations.

Sullivan spent more than a month at Easton, working on the logistical plans for the expedition before he took to the field in mid-June. It took his men more than a month to reach Wyoming. Clinton's troops were also delayed, being forced to dam Otsego Lake just to get their supplies and munitions to Tioga.

Easton, working on the logistical plans for the expedition before he took to the field in mid-June. It took his men more than a month to reach Wyoming. Clinton's troops were also delayed, being forced to dam Otsego Lake just to get their supplies and munitions to Tioga.

Plagued by supply and morale problems, Brodhead's force destroyed some Indian villages in the Allegheny valley but never reached its rendezvous with the other forces. Beginning in late August, however, Sullivan and Clinton conducted a successful "scorched earth" operation through the heart of Iroquoia, burning more than forty Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga villages and seizing or destroying enormous quantities of food.

Their focus on the ecological destruction of Iroquoian society was not accidental. Washington's planning made it clear that he wanted to cripple Indian tribes in order to eliminate them as a factor of war. In this sense, the Continental Army's tactics for fighting Indians were similar to those used on the Pennsylvania frontier during the French and Indian War by Colonel John Armstrong when he attacked the Delaware village of Kittanning in 1756. Faced with such a large invading force, the Indians withdrew from their villages, offering only sporadic guerilla resistance and seeking British protection at Niagara. There were few major battles, and casualties were relatively light on both sides.

Kittanning in 1756. Faced with such a large invading force, the Indians withdrew from their villages, offering only sporadic guerilla resistance and seeking British protection at Niagara. There were few major battles, and casualties were relatively light on both sides.

Sullivan returned from the expedition confident that he had achieved his objectives. The hardships in Indian country were considerable. Parts of Iroquoia lay in ruins. Thousands of Indian refugees besieged the British stronghold at Fort Niagara, where redcoats had to feed them during the subsequent winter, one of the harshest in the eighteenth century. Crops failed, and the Hudson River froze at New York City.

Battered, but their spirits unbroken, the Iroquois and Loyalists continued their raiding along the New York and Pennsylvania frontier until the Peace of Paris ended the war in 1783. On October 22, 1784, the Americans demanded that the Iroquois abandon all claims to territory in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and western New York in an agreement they called the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. Abandoned by their former British allies, the Iroquois found themselves with little means to resist the seizure of their homelands by New York in the years that followed. Those who did not move to Canada or the Ohio country were confined to a few small reservations by 1800.

Years later, the Iroquois chief Cornplanter remembered the campaign in a speech to President George Washington: "When your army entered the country of the Six Nations, we called you Town Destroyer: and to this day when that name is heard our women look behind them and turn pale, and our children cling close to the necks of their mothers."

The Sullivan Campaign had its roots in the chronic clashes and resentments between Indians and colonists caused by the

Sullivan assembled 2,500 men at Easton, planning to march northwest through Wyoming into Iroquoia during the early spring of 1779. There he would meet and cooperate with two other wings of the expedition. General James Clinton's forces were to advance from the Mohawk Valley southwest to meet Sullivan near Tioga, and Pennsylvania Colonel Daniel Brodhead's smaller force was to travel up the Allegheny River from Fort Pitt to meet the main body of troops in the Genesee country west of the Finger Lakes. Collectively, these three forces totaled approximately 5,000 men and reflected Washington's fondness for complex, multi-pronged strategic operations.

Sullivan spent more than a month at

Plagued by supply and morale problems, Brodhead's force destroyed some Indian villages in the Allegheny valley but never reached its rendezvous with the other forces. Beginning in late August, however, Sullivan and Clinton conducted a successful "scorched earth" operation through the heart of Iroquoia, burning more than forty Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga villages and seizing or destroying enormous quantities of food.

Their focus on the ecological destruction of Iroquoian society was not accidental. Washington's planning made it clear that he wanted to cripple Indian tribes in order to eliminate them as a factor of war. In this sense, the Continental Army's tactics for fighting Indians were similar to those used on the Pennsylvania frontier during the French and Indian War by Colonel John Armstrong when he attacked the Delaware village of

Sullivan returned from the expedition confident that he had achieved his objectives. The hardships in Indian country were considerable. Parts of Iroquoia lay in ruins. Thousands of Indian refugees besieged the British stronghold at Fort Niagara, where redcoats had to feed them during the subsequent winter, one of the harshest in the eighteenth century. Crops failed, and the Hudson River froze at New York City.

Battered, but their spirits unbroken, the Iroquois and Loyalists continued their raiding along the New York and Pennsylvania frontier until the Peace of Paris ended the war in 1783. On October 22, 1784, the Americans demanded that the Iroquois abandon all claims to territory in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and western New York in an agreement they called the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. Abandoned by their former British allies, the Iroquois found themselves with little means to resist the seizure of their homelands by New York in the years that followed. Those who did not move to Canada or the Ohio country were confined to a few small reservations by 1800.