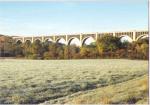

![header=[Marker Text] body=[This reinforced concrete structure was the largest of its kind ever built when it went into service in 1915 on the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. The bridge, 2,375 feet long and rising 240 feet above Tunkhannock Creek, was the focal point of a 39.6-mile relocation between Clarks Summit and Hallstead. The novelist Theodore Dreiser called this viaduct "one of the true wonders of the world."] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-1B9-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0b1w6-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Tunkhannock Viaduct

Region:

Poconos / Endless Mountains

County:

Wyoming

Marker Location:

Nicholson Bridge, US 11, 1/2 mile S of Nicholson

Dedication Date:

September 15, 1995

Behind the Marker

Railroad engineering experts were constantly in search of the best building materials for the bridges they needed to build to span valleys and rivers. In the 1830s and 1840s, wood was the material of choice, for it was cheap, readily available, and easily cut to the length and depth needed. But wood needed constant maintenance and was vulnerable to fire. Stone construction was durable but costly, and required skilled labor to cut and assemble.

Iron, appearing on the scene in the 1840s, seemed to be the perfect answer until design weaknesses, metal fatigue, and overloading caused spectacular crashes, whose accounts, splashed across the front pages of newspapers, announced scores of passenger fatalities. Soon after 1900, railroads began to make extensive use of reinforced concrete.

When the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (DL&W) rerouted and straightened its main line in the early 1900s, the resulting realignment required deep cuts, high fills (embankments), and massive bridges. Named for the creek it crosses, the Tunkhannock Viaduct -also known as Nicholson Bridge because of its location - towers above the town of Nicholson, nineteen miles north of Scranton. Today it remains the largest reinforced-concrete structure in the world.

Completed in 1882 after Jay Gould used his position on the board to force an extension to the Great Lakes and a link with his Wabash Railroad, DL&W connected New York City (via ferry to its passenger terminal on the Hudson River at Hoboken, N.J.) with Buffalo, N.Y. Its 410-mile main line meandered across New Jersey, entered Pennsylvania several miles south of Delaware Water Gap, climbed through the Pocono Mountains to Scranton, and then cut through even more rugged territory before crossing into New York State a few miles southeast of Binghamton.Following the topography, the line wove its way through a crooked and hilly land, a route that slowed trains and required multiple helper locomotives for heavy freights.

Jay Gould used his position on the board to force an extension to the Great Lakes and a link with his Wabash Railroad, DL&W connected New York City (via ferry to its passenger terminal on the Hudson River at Hoboken, N.J.) with Buffalo, N.Y. Its 410-mile main line meandered across New Jersey, entered Pennsylvania several miles south of Delaware Water Gap, climbed through the Pocono Mountains to Scranton, and then cut through even more rugged territory before crossing into New York State a few miles southeast of Binghamton.Following the topography, the line wove its way through a crooked and hilly land, a route that slowed trains and required multiple helper locomotives for heavy freights.

As president of DL&W, William Haynes Truesdale recognized the value of a straighter, more level alignment. In 1899, flush with profits from both the mining and hauling of anthracite coal, the Lackawanna had the opportunity to build the super-railroad that Truesdale had envisioned. The first step was to straighten the line from Hoboken to Delaware Water Gap. This he accomplished with the $11 million New Jersey Cutoff, built between 1908 and 1911. Incorporating a three-mile-long, 100-foot-high earthen fill containing six million cubic yards, the cutoff shortened the previous thirty-nine-mile route by eleven miles.

Costing $14 million, the Nicholson Cutoff cut three and one-half miles off the previous forty-three-mile route and eliminated sixty percent of the old route's curvature. Begun in 1912, construction continued for three and one-half years. Like the earlier project, the Nicholson Cutoff used two large concrete bridges, Martins Creek Viaduct (eleven arches, 1,600 feet long and 150 feet high) and the crowning jewel of the project, the Tunkhannock.

To complete the bridge, the contracting firm of Flickwir and Bush employed a workforce of about 500 men, some of whom worked nearly 300 feet off the ground on and around temporary construction towers and cables. In the course of work, two men fell to their deaths. Soaring 240 feet above the valley floor, Tunkhannock Viaduct stretched for 2,375 feet across ten 180 foot arches and two 100 foot arches. It consumed 167,000 cubic yards of concrete (about 350,000 tons) and 1,140 tons of reinforcing steel. When completed in 1915, it was twice as long and more than twice as high as the 1848 stone-arch Starrucca Viaduct, which lies about twenty-five miles northeast of Nicholson.

Starrucca Viaduct, which lies about twenty-five miles northeast of Nicholson.

At the dedication ceremonies on November 6, 1915, Pennsylvania Gov. Martin C. Brumbaugh compared the Tunkhannock Viaduct to the Walnut Lane Bridge over the Wissahickon Creek in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park which, when it opened in December 1908, was hailed as the largest concrete bridge in the state. (Walnut Lane's main span measured 233 feet long and rose 147 feet over the valley.) Your could put a dozen Walnut Street bridges under this monster and not notice them,"

Martin C. Brumbaugh compared the Tunkhannock Viaduct to the Walnut Lane Bridge over the Wissahickon Creek in Philadelphia's Fairmount Park which, when it opened in December 1908, was hailed as the largest concrete bridge in the state. (Walnut Lane's main span measured 233 feet long and rose 147 feet over the valley.) Your could put a dozen Walnut Street bridges under this monster and not notice them,"  quipped Brumbaugh.

quipped Brumbaugh.

After the Cutoff opened, DL&W transferred ownership of its old right-of-way to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, which used it for an improved highway named, appropriately, Lackawanna Trail, which later became part of what is now U.S. 11.

Ownership of the viaduct changed in 1960 when DL&W merged with the Erie Railroad to form the Erie Lackawanna (EL). Regular daily passenger service ended in 1970 with the discontinuance of EL's last long-haul intercity train, the Lake Cities, which connected Hoboken with Chicago via Scranton. EL declared bankruptcy in 1972 and was merged into Consolidated Rail Corporation in 1976. In 1980, Conrail sold the line to Delaware and Hudson Railway, which later became part of the Canadian Pacific Railway system. Today, freight trains continue to cross Tunkhannock Viaduct, now under the ownership of Norfolk Southern, which became the new owner of the bridge in 2015.

"A thing colossal and impressive. Those arches! How really beautiful they were. How symmetrically planned! And the smaller arches above, how delicate and lightsomely graceful! It is odd to stand in the presence of so great a thing in the making and realize that you are looking at one of the true wonders of the world."

–Theodore Dreiser in A Hoosier Holiday, 1916Railroad engineering experts were constantly in search of the best building materials for the bridges they needed to build to span valleys and rivers. In the 1830s and 1840s, wood was the material of choice, for it was cheap, readily available, and easily cut to the length and depth needed. But wood needed constant maintenance and was vulnerable to fire. Stone construction was durable but costly, and required skilled labor to cut and assemble.

Iron, appearing on the scene in the 1840s, seemed to be the perfect answer until design weaknesses, metal fatigue, and overloading caused spectacular crashes, whose accounts, splashed across the front pages of newspapers, announced scores of passenger fatalities. Soon after 1900, railroads began to make extensive use of reinforced concrete.

When the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad (DL&W) rerouted and straightened its main line in the early 1900s, the resulting realignment required deep cuts, high fills (embankments), and massive bridges. Named for the creek it crosses, the Tunkhannock Viaduct -also known as Nicholson Bridge because of its location - towers above the town of Nicholson, nineteen miles north of Scranton. Today it remains the largest reinforced-concrete structure in the world.

Completed in 1882 after

As president of DL&W, William Haynes Truesdale recognized the value of a straighter, more level alignment. In 1899, flush with profits from both the mining and hauling of anthracite coal, the Lackawanna had the opportunity to build the super-railroad that Truesdale had envisioned. The first step was to straighten the line from Hoboken to Delaware Water Gap. This he accomplished with the $11 million New Jersey Cutoff, built between 1908 and 1911. Incorporating a three-mile-long, 100-foot-high earthen fill containing six million cubic yards, the cutoff shortened the previous thirty-nine-mile route by eleven miles.

Costing $14 million, the Nicholson Cutoff cut three and one-half miles off the previous forty-three-mile route and eliminated sixty percent of the old route's curvature. Begun in 1912, construction continued for three and one-half years. Like the earlier project, the Nicholson Cutoff used two large concrete bridges, Martins Creek Viaduct (eleven arches, 1,600 feet long and 150 feet high) and the crowning jewel of the project, the Tunkhannock.

To complete the bridge, the contracting firm of Flickwir and Bush employed a workforce of about 500 men, some of whom worked nearly 300 feet off the ground on and around temporary construction towers and cables. In the course of work, two men fell to their deaths. Soaring 240 feet above the valley floor, Tunkhannock Viaduct stretched for 2,375 feet across ten 180 foot arches and two 100 foot arches. It consumed 167,000 cubic yards of concrete (about 350,000 tons) and 1,140 tons of reinforcing steel. When completed in 1915, it was twice as long and more than twice as high as the 1848 stone-arch

At the dedication ceremonies on November 6, 1915, Pennsylvania Gov.

After the Cutoff opened, DL&W transferred ownership of its old right-of-way to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, which used it for an improved highway named, appropriately, Lackawanna Trail, which later became part of what is now U.S. 11.

Ownership of the viaduct changed in 1960 when DL&W merged with the Erie Railroad to form the Erie Lackawanna (EL). Regular daily passenger service ended in 1970 with the discontinuance of EL's last long-haul intercity train, the Lake Cities, which connected Hoboken with Chicago via Scranton. EL declared bankruptcy in 1972 and was merged into Consolidated Rail Corporation in 1976. In 1980, Conrail sold the line to Delaware and Hudson Railway, which later became part of the Canadian Pacific Railway system. Today, freight trains continue to cross Tunkhannock Viaduct, now under the ownership of Norfolk Southern, which became the new owner of the bridge in 2015.