![header=[Marker Text] body=[At his print shop here, Robert Bell published the first edition of Thomas Paine's Revolutionary pamphlet in January 1776. Arguing for a republican form of government under a written constitution, it played a key role in rallying American support for independence.] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-157-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0a8n2-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Common Sense

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

SE corner of S 3rd St. and Thomas Paine Place (Chancellor St.), Philadelphia South

Behind the Marker

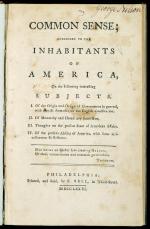

The publication of Thomas Paine's Common Sense on January 10, 1776 in Philadelphia was a watershed of the American Revolution. At the time, a majority of colonists were still wavering about the idea of independence from Great Britain, but Paine's pamphlet galvanized opposition to the Crown and served as the final catalyst for political separation. Through this pamphlet, Paine joined the ranks of the founding fathers, even though he did not receive credit for his remarkable achievement until two centuries later.

Born in Thetford, England, on January 29, 1737, Tom Paine spent the first thirty-seven years of his life in obscurity. Having lost his job as a poorly paid tax collector for trying to obtain better conditions for his fellow workers, he immigrated to America in November 1774.

Arriving in Philadelphia with letters of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met in London, Paine soon secured employment as an editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine. While the printer, Scotsman Robert Aitken, set the policies for the newspaper, ensuring that all articles would "avoid the suspicion of prejudice on the controversial issues of religion and politics," Paine submitted nearly a fourth of all published articles, writing under the pseudonyms of "Atlanticus," "Aesop," and "Vox Populi."

Most of his early contributions were light-hearted, informative essays, but his best works were those that violated Aitken's policy by lashing out at British rule. When Paine accused the English government of limiting the "social and political opportunities" of American women and encouraging Indians to attack innocent white settlers, then concluded with a prophetic statement that equated American independence with the "cause of God and humanity," Aiken dismissed him. But colonists wanted to read more.

After the British attacks on Lexington and Concord in the spring of 1775 evoked growing sympathy for the American cause, some of Congress's greatest advocates of independence, including Benjamin Franklin and

Benjamin Franklin and  Benjamin Rush, planned to use Paine to test public opinion before making a definitive commitment themselves. When they encouraged him to detail his arguments in a single pamphlet Paine obliged by writing Common Sense.

Benjamin Rush, planned to use Paine to test public opinion before making a definitive commitment themselves. When they encouraged him to detail his arguments in a single pamphlet Paine obliged by writing Common Sense.

From late autumn 1775 until the publication of the tract in January, 1776, Paine spent his days in his rented rooms along the Philadelphia waterfront, writing about revolution. At nightfall, he visited taverns to engage in political debate and drink. Paine was a painstakingly diligent writer. A brief paragraph might take him days or even weeks, because he scrutinized each sentence. Finally, on January 10, 1776, Paine published Common Sense, a forty-seven-page pamphlet that advocated American independence in language the common man could understand and, ultimately, defend.

In it, he depicted King George as a tyrant, a co-conspirator in Parliament's attempt to destroy the natural rights of the American colonists. Using strong, richly graphic images that aroused anger in his readers, Paine compared George to a "father-king" who relished his children, the Americans, as his main meal. "Even brutes do not devour their young," he wrote. "Out of fear for their freedom, many have fled England to America" in the hope of "escaping the cruelty of the monster." Paine believed that monarchy was useless, having "little more to do than make war and give away places at court." He argued that "Americans should not feel any obligation to a crowned ruffian who sanctions war against them." Nor did Paine spare any criticism of the mixed constitution of Great Britain, considered at the time to be the most perfectly balanced form of government in the world with its divisions of King, Lords, and Commons.

"Why is the constitution of England so sickly?" Paine asked. "Because the monarchy hath poisoned the republic, the crown hath engrossed the commons." A free America, he argued, would do well to learn from England's mistakes and draft a republican constitution with annual assemblies and a president who would be chosen each year from a different colony. A unicameral legislature would be empowered to pass laws, but only by a three-fifths majority. "Let this republican charter be brought forth placed on the divine law, the word of God," he urged. "Let a crown be placed thereon, so that the world may know, that in America THE LAW IS KING."

Turning next to the "present state of American affairs," Paine argued that the situation had become so intolerable that Americans must "cease negotiating for a repeal of the Parliamentary acts and separate from England." By declaring her independence, America would ensure a strong, lasting commerce, the happiness of its people, and protection from a hopelessly corrupt Europe. Like a preacher urging his congregation to embark on a divinely inspired mission, Paine urged his readers: "O! Ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only the tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth!"

Common Sense struck a resounding chord within the American conscience - and the timing couldn't have been better. Only a few days before its release, King George delivered his opening speech to Parliament calling for suppression of the American rebellion. Common Sense gave the Crown a direct and unequivocal response that was instantly copied, parodied, and translated into the language of every country that sympathized with the American cause. Nearly 120,000 copies were sold in the first three months after its release, and by the end of the year about 500,000 copies had found their way into bookstores, private libraries, and taverns in both Europe and America. Common Sense convinced many Americans who had previously been neutral on the subject of independence that they should separate from England. On July 2, 1776, when Congress voted for American independence, Paine's efforts were realized.

During the war, Paine enlisted in the Continental Army, and wrote a series of essays designed to inspire the soldiers and that were later published collectively as The American Crisis. He then contributed the profits from its sale to the army. Returning to England after the Revolutionary War, Paine became embroiled in the political debates ignited by the French Revolution. His Rights of Man, which defended that revolution against the attacks of British Parliamentarian Edmund Burke, proved to be even more inflammatory than Common Sense. Charged with seditious libel, Paine escaped to France, where he was elected to the French National Convention and wrote his final great work, Age of Reason, in which he attacked the basic principles of Christianity.

In 1802, Paine returned to America a bitter and disillusioned man. His attacks on Christianity aroused waves of anger around the nation, making him a "person to be avoided, a character to be feared." He lived the final years of his life as an outcast, and died in New York City on June 8, 1809.

Today, Thomas Paine's Common Sense is widely regarded as a powerful expression of the American mind, just a step in importance below the Declaration of Independence. His greatest legacy, however, may well have been his faith in the ability of common people to determine their own political destiny.

Common Sense is widely regarded as a powerful expression of the American mind, just a step in importance below the Declaration of Independence. His greatest legacy, however, may well have been his faith in the ability of common people to determine their own political destiny.

Born in Thetford, England, on January 29, 1737, Tom Paine spent the first thirty-seven years of his life in obscurity. Having lost his job as a poorly paid tax collector for trying to obtain better conditions for his fellow workers, he immigrated to America in November 1774.

Arriving in Philadelphia with letters of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met in London, Paine soon secured employment as an editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine. While the printer, Scotsman Robert Aitken, set the policies for the newspaper, ensuring that all articles would "avoid the suspicion of prejudice on the controversial issues of religion and politics," Paine submitted nearly a fourth of all published articles, writing under the pseudonyms of "Atlanticus," "Aesop," and "Vox Populi."

Most of his early contributions were light-hearted, informative essays, but his best works were those that violated Aitken's policy by lashing out at British rule. When Paine accused the English government of limiting the "social and political opportunities" of American women and encouraging Indians to attack innocent white settlers, then concluded with a prophetic statement that equated American independence with the "cause of God and humanity," Aiken dismissed him. But colonists wanted to read more.

After the British attacks on Lexington and Concord in the spring of 1775 evoked growing sympathy for the American cause, some of Congress's greatest advocates of independence, including

From late autumn 1775 until the publication of the tract in January, 1776, Paine spent his days in his rented rooms along the Philadelphia waterfront, writing about revolution. At nightfall, he visited taverns to engage in political debate and drink. Paine was a painstakingly diligent writer. A brief paragraph might take him days or even weeks, because he scrutinized each sentence. Finally, on January 10, 1776, Paine published Common Sense, a forty-seven-page pamphlet that advocated American independence in language the common man could understand and, ultimately, defend.

In it, he depicted King George as a tyrant, a co-conspirator in Parliament's attempt to destroy the natural rights of the American colonists. Using strong, richly graphic images that aroused anger in his readers, Paine compared George to a "father-king" who relished his children, the Americans, as his main meal. "Even brutes do not devour their young," he wrote. "Out of fear for their freedom, many have fled England to America" in the hope of "escaping the cruelty of the monster." Paine believed that monarchy was useless, having "little more to do than make war and give away places at court." He argued that "Americans should not feel any obligation to a crowned ruffian who sanctions war against them." Nor did Paine spare any criticism of the mixed constitution of Great Britain, considered at the time to be the most perfectly balanced form of government in the world with its divisions of King, Lords, and Commons.

"Why is the constitution of England so sickly?" Paine asked. "Because the monarchy hath poisoned the republic, the crown hath engrossed the commons." A free America, he argued, would do well to learn from England's mistakes and draft a republican constitution with annual assemblies and a president who would be chosen each year from a different colony. A unicameral legislature would be empowered to pass laws, but only by a three-fifths majority. "Let this republican charter be brought forth placed on the divine law, the word of God," he urged. "Let a crown be placed thereon, so that the world may know, that in America THE LAW IS KING."

Turning next to the "present state of American affairs," Paine argued that the situation had become so intolerable that Americans must "cease negotiating for a repeal of the Parliamentary acts and separate from England." By declaring her independence, America would ensure a strong, lasting commerce, the happiness of its people, and protection from a hopelessly corrupt Europe. Like a preacher urging his congregation to embark on a divinely inspired mission, Paine urged his readers: "O! Ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose not only the tyranny but the tyrant, stand forth!"

Common Sense struck a resounding chord within the American conscience - and the timing couldn't have been better. Only a few days before its release, King George delivered his opening speech to Parliament calling for suppression of the American rebellion. Common Sense gave the Crown a direct and unequivocal response that was instantly copied, parodied, and translated into the language of every country that sympathized with the American cause. Nearly 120,000 copies were sold in the first three months after its release, and by the end of the year about 500,000 copies had found their way into bookstores, private libraries, and taverns in both Europe and America. Common Sense convinced many Americans who had previously been neutral on the subject of independence that they should separate from England. On July 2, 1776, when Congress voted for American independence, Paine's efforts were realized.

During the war, Paine enlisted in the Continental Army, and wrote a series of essays designed to inspire the soldiers and that were later published collectively as The American Crisis. He then contributed the profits from its sale to the army. Returning to England after the Revolutionary War, Paine became embroiled in the political debates ignited by the French Revolution. His Rights of Man, which defended that revolution against the attacks of British Parliamentarian Edmund Burke, proved to be even more inflammatory than Common Sense. Charged with seditious libel, Paine escaped to France, where he was elected to the French National Convention and wrote his final great work, Age of Reason, in which he attacked the basic principles of Christianity.

In 1802, Paine returned to America a bitter and disillusioned man. His attacks on Christianity aroused waves of anger around the nation, making him a "person to be avoided, a character to be feared." He lived the final years of his life as an outcast, and died in New York City on June 8, 1809.

Today, Thomas Paine's